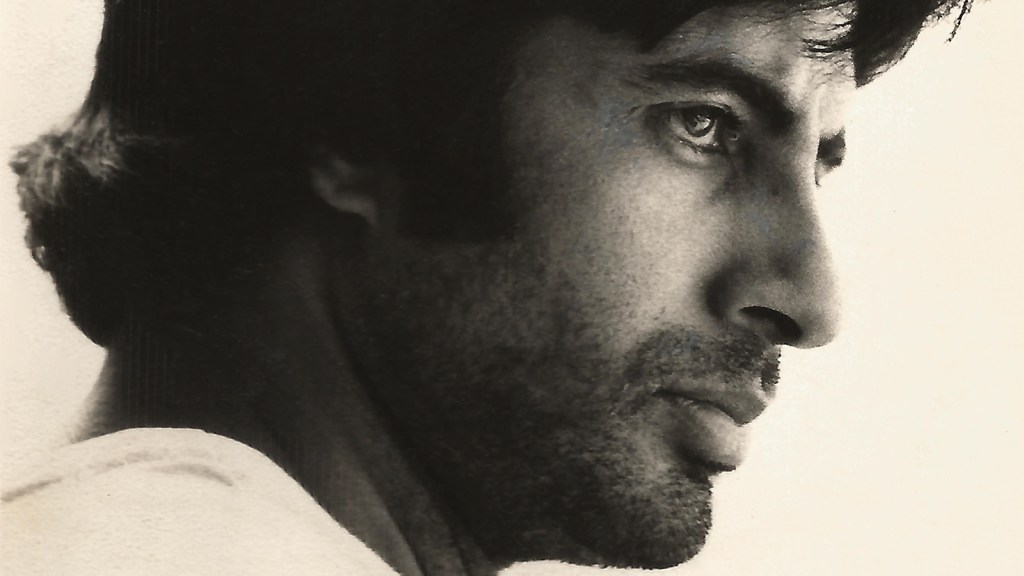

This year I was once again tapped by Sydney Film Festival to write program notes for the upcoming 70th edition. Once again, along with the assortment of new films assigned to me, I was handed the enjoyable task of writing up a program of classic films from India. Last year it was the Satyajit Ray retrospective — a program of 10 films so moving and inspiring they practically changed my life, as I wrote in my essay about it. This year it was a shorter program with a very different feel: four 1970s Bollywood classics starring Amitabh Bachchan, a movie star so storied and iconic in India and among Bollywood fans worldwide he’s practically a one-man cultural institution.

This mini-program, entitled Bachchan: Back to the Beginning was picked from a larger program of the same name that toured India last year to mark Bachchan’s 80th birthday. It was a big success, and not only affirmed Bachchan’s enduring appeal in his home country, but also proved the value of screening classic cinema in theaters for today’s audiences.

I’m going to start this preview of SFF by spending some time on this terrific Bachchan program, which was definitely the highlight for me. After that I’ll get to some of the other titles, several of which were very good and that I recommend. I only wrote up 11 films this year, so this is hardly a comprehensive preview of the fest; it’s just my thoughts about the little corner of the program I worked on. Hopefully a couple of the titles grab you!

Several of the new films here are also from the Indian subcontinent — whether by coincidence or because the programmers think I’m good at writing those ones up, I’m not sure! And several of them concern politics or human rights — again, I think because they’ve decided I know how to tackle political content in cinema (and that’s a nice compliment).

By the way, SFF runs from June 7 to 18 so if you’re in the Sydney area you still have plenty of time to make plans and grab tickets.

I hadn’t seen any of these Bachchan titles — in fact I hadn’t seen any Bollywood movies from the 1970s. I love Bollywood, but I’m hardly an expert on the form; I’ve seen maybe three dozen Bollywood films in my life, most of them from the 90s or later. So once again this assignment was a learning curve for me, and a much-appreciated one.

These four Bachchan films — Deewaar (Yash Chopra, 1975), Amar Akbar Anthony (Manmohan Desai, 1977), Don (1978), and Kaala Patthar (Yash Chopra, 1979) — paint with much broader strokes than the exquisite arthouse films of Ray. All four are quintessential examples of Hindi film populism. And while I wouldn’t go as far as to say they represent the best of world cinema the way Ray’s films do, I still found them tremendously enjoyable, uplifting, and rewarding in their own very different way. Their populism, their wild mix of different genres and styles from melodrama to action to musical, and their often kitschy tone bely how truly substantial they are.

It’s easy enough to dismiss Bollywood films as mere fantasias, popcorn films for the masses filled with cliched romance, cheesy plot twists, exotic locations and showstopping musical numbers. And they are all of that. But then you actually sit and watch one of the good ones and realize how much beauty, social commentary, and genuine feeling they pack in along with the extravaganza and the tropes. These four films filled me with delight, and moved me to tears several times over eleven-plus hours (all of them are quite long, at almost three hours each); and that’s about all you need for a film to qualify as worthwhile cinema as far as I’m concerned.

Aside from the typical Bollywood focuses on romance, family drama, and morality, each one of these Bachchan films confronts social issues such as class and poverty. They are often refreshingly progressive, with proud displays of multiculturalism, and admirably early efforts to tackle gender disparities.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Bollywood has always been a beacon for progressivism and multiculturalism in India. There have always been Muslims involved, both in front of and behind the camera; it’s often been a safe space for LGBT Indians to work and contribute to culture; and progressive themes such as feminism and workers’ rights have often been prominently featured in the stories. These are among the reasons for the fascist president Jarendra Modi’s destructive and ongoing culture war on the film industry.

I knew all that going in, but still it was delightful to see just how progressive, socially conscious, and sometimes even outright leftist these fortysomething-year-old movies are. The 1970s was a decade of great social upheaval in India, and it shows here. Bachchan was labelled the “Angry Young Man of Bollywood” at a time when his massive fan base were angry themselves for a lot of legitimate reasons — tremendous growth in Indian industry on the backs of hyper-exploited labor, massive levels of urban and rural poverty, state repression of protest movements.

In all of these films, Bachchan portrays someone who’s been beaten down by life — an impoverished worker, an orphan, a migrant — and who rises out of poverty to confront the wealthy or corrupt with great courage and dignity. Bachchan’s magnetic, overpowering screen presence made him the ideal avatar for these tales of the common people. Watching him as a young performer for the first time, I thought of him as a cross between Shah Rukh Khan and Denzel Washington, with the former’s universal appeal and ridiculously good looks, and the latter’s smoldering intensity and righteousness. Bachchan can play a character who’s hurt, aggrieved, and mad at the world, without making him excessively bitter or mean. His heroes are always there to help other victims of the system, and always loyal to family and friends; and when they open up to romance — as they inevitably do, because this is Bollywood — it’s like the sun breaking through the clouds. His screen presence is masculine, but in a decidedly nontoxic way. His characters are tough guys, but they’re also gentle, and they wear their hearts on their sleeves.

Meanwhile his great range and versatility as an entertainer meant he could step outside of his Angry Young Man persona in order to cut loose for a musical number. Or even better to satirize himself, as he does in Don, in a dual role as a ruthless gangster and a jolly street performer; or in his comic turn as a lapsed Christian bar owner in Amar Akbar Anthony.

These films have plots that are so high-concept they’re like fables. In Amar Akbar Anthony, three young boys are orphaned after their parents are attacked by a ruthless gangster, and are then raised separately as a Hindu, a Muslim, and a Christian. Naturally, years later they band together as adults without realizing they are related — or that their parents are still alive. In Deewaar, two brothers who are raised in desperate poverty find themselves on opposing sides of the law when one becomes a gangster and the other a cop. In Kaala Patthar, a sea captain who is shattered by guilt after abandoning hundreds of shipmates to drown is given a shot at redemption in his a new life as a humble coal miner. In Don, a poor migrant is roped by police into impersonating his suave and dangerous lookalike.

The plots may be contrived, but you can’t deny the social consciousness of these films. Taken together, these four stories are such an interesting snapshot of 70s India, leaving a vivid impression of a terribly unequal society — a place where a few lucky or corrupt individuals make their fortunes while the masses toil and go without.

The two films directed by Yash Chopra are especially sharp on the topics of class, labor and poverty. Deewaar begins with a militant unionist (Satyendra Kapoor) confronting a hated mining boss, only to be doublecrossed into signing a contract that betrays his comrades — who angrily threaten him and drive him into exile. His wife Sumitra (Nirupa Roy) and his two young sons are left to fend for themselves on the streets of Mumbai, making their home in what amounts to a tent in a slum (like millions in the city do in real life). Early on, Sumitra must make the heartbreaking choice of which of her sons to send to school, because she can’t afford to send both. Her son Vijay (Bachchan) is the one who must do without an education; he grows up to be a dock worker with a burning resentment for the upper classes. Then, after several Bollywood twists of fate, Vijay is recruited into a local gang and quickly rises through the ranks to become a powerful crime lord — albeit with a Robin Hood streak. Deewaar was instrumental in making Bachchan a household name in India, and it’s easy to see why: his charisma in this role is off the charts. Meanwhile, Vijay’s brother Ravi (Shashi Kapoor), the more fortunate, more educated one, attends police academy; his first assignment upon graduation is to bust his own brother’s gang.

As with most of these films, there is a fair bit of religion and moralizing in the story, and a sentimental and fairly conservative view of the family as the source of everything good in society. But at the same time it’s hard to shake the feeling that all of the conflict and tragedy faced by Vijay and Ravi have been determined not by their own moral choices but by oppressive social forces beyond their control. “The poor have to bear everything,” as Sumitra laments. The role that poverty plays in crime is directly addressed by the screenplay — not only in Vijay’s character arc, but also in an unsettling scene in which Ravi, the rookie cop, shoots and kills a thief who was fleeing with some food for his family. Overwhelmed with guilt, he visits the dead thief’s parents to break the news to them and to try to make amends, and the young man’s mother lashes out in grief and anger. “Does your justice shoot only the poor? What had my son done?” she cries. “He stole some bread for his parents. If you’re such a legal eagle, go and shoot the ones who hoard grain in their warehouses!”

Kaala Patthar takes these themes even further: its tale of coal miners uniting in their struggle against the deadly greed of their boss is overtly, beautifully anticapitalist — there’s no other way to put it. Picture something like John Sayles goes to Bollywood. The story is based on the horrifying real-life Chasnala mining disaster of 1975, in which 375 workers died when the walls of a mine collapsed and flooded due to management’s negligence. It was the deadliest mining disaster in Indian history; and surely the pain and rage it aroused in the public is one reason why the screenplay depicts the boss (Prem Chopra) as an irredeemably evil villain, a monster void of humanity, who says things like, “Are we running these mines for the safety of these workers, or for our profit?”

Cartoonish it may be, but it’s so refreshing and dare I say reasonable compared to the more usual cinematic depictions of the captains of industry as sophisticated, hypercompetent and better than the rest of us.

Shashi Kapoor plays Ravi, a bighearted engineer who attempts to organize the mine workers. As wonderfully appealing as Kapoor is (he’s so boyishly charismatic you’d watch him read the phone book, and his musical numbers are splendid), this plotline is a bit muddled. There’s a scene in which he talks an angry crowd of workers out of striking and occupying the boss’s office, so that he can negotiate on their behalf. His intervention is well-meaning, but ultimately destructive, especially since the boss is already scheming to send the miners into more danger. Whether intended or not it’s an apt analogy for the obstructionism and uselessness of union bureaucrats.

Meanwhile, Bachchan simmers and sulks as Vijay, the disgraced sea officer who seeks to bury his sorrow and shame in the notoriously deadly coal mine. He’s indifferent to his own comfort or safety, but very protective of his fellow workers and the poor residents of the mining town — a coal-dust-smeared proletarian avenging angel, fallen from the upper class. There are several great scenes of him righteously confronting the boss, his henchmen and various other bullies. “You are not human,” Vijay seethes at the boss at one point. “You are an animal. You are a man-eater who drinks the blood of these laborers and eats their flesh.”

I just love the rabble-rousing vibe of this film, and its depiction of mass solidarity in the climactic scenes as Ravi and Vijay rally their fellow workers for a desperate rescue operation. The view of the conflict between labor and capital is crystal clear, and never compromised.

I mean, just take this line spoken by Parveen Babi, who plays a journalist investigating the mine’s safety record: “All the learned people think that the wealth obtained from the land should belong to everyone, and not just one person.” That’s just undiluted Marxism — it cracks me up to imagine how mad that must have made the bosses and conservative pundits when this film was new.

The other two films in the mini-program are less weighty in tone, but still have plenty of interesting social and political angles. Underlying the absurdly convoluted crime capers in Don is a stinging commentary on the lot of the migrant poor in Mumbai. Bachchan’s dual roles are so interesting for how he contrasts the city’s rich and poor in his portrayals of the wealthy, debonair yet sociopathic crime boss and the hapless, happy-go-lucky migrant street performer Vijay. Don wears three-piece suits, sips cocktails and talks like a smooth Bombay hipster. Vijay goes barefoot, his teeth are stained red with paan (betel leaf), and he grins sheepishly while talking in a broad country accent. It’s so funny watching Bachchan chew scenery as well as paan while playing the Indian equivalent of a redneck. Things get even loopier during the long stretches when Vijay impersonates Don and things double back on themselves.

There’s a grittiness and dustiness to the Mumbai street scenes featuring Vijay that I don’t think are fake; in one musical number, which happens to be an ode to the rural poor, he dances in the dirt in an unpaved square. This is the wonderful thing about 70s Bollywood. Before it became feasible and trendy to shoot in exotic overseas locations (Australia was a popular setting in the early 2000s), Bollywood flicks were made on location at home — often with extras who were clearly picked off the street that day and filled with smiles, completely psyched to be part of it all. This gives the films a wonderful sense of time and place, an almost documentary quality, however fanciful the goings-on.

Aside from its depiction of class, Don is great fun for its pastiches of various 60s and 70s crime and spy genres. The Blaxploitation flicks of the 70s were clearly on the minds of the creators — the soundtrack is replete with wah-wah guitar and disco beats alongside the usual Bollywood jams. The wide-lapel 70s fashions are outrageously colorful, and the title sequence is downright psychedelic. American cop shows of the 70s such as Starsky and Hutch seem to be an influence as well, and there’s more than a little James Bond in the mix, especially in all the scenes of decadent nightclubs, hotels and pool parties.

I was especially impressed by the overt feminism of Zeenat Aman’s role as an undercover rogue out to avenge her brother’s murder at the hands of Don. She’s the very opposite of a typical Bollywood leading lady: for much of the film she sports short hair, pants and an RBF, and she leaves the bruised and battered bodies of her male foes everywhere she goes. She doesn’t take part in any musical numbers either. She does ultimately turn out to be a love interest for Vijay (that is when she’s not trying to kill him, thinking he’s Don) but that seems almost an afterthought compared to her ass-kicking.

Amar Akbar Anthony is especially poignant for the interfaith solidarity between the three lead characters (played by Vinod Khanna, Rishi Kapoor, and Bachchan respectively; all of them are outstanding). Given the horrifying rise in anti-Muslim hate and violence in Modi’s India today, the idea of brotherhood between Hindu, Muslim and Christian is as timely and urgent as ever.

The film is really committed to showing all three religions in the best light too — there are two lovely scenes that depict miracles in a Hindu temple and a church, respectively; and an extended musical interlude with Kapoor performing a qawwali number so stirring and sublime I felt like I was going to levitate out of my chair and float away. (Here’s a really interesting article about qawwali and the influence of Muslim and Sufi music and culture on Bollywood.)

Say what you will about religion — but anyway the religious themes are not as important as the social solidarity the film depicts (and hopefully inspires in the audience).

Amar Akbar Anthony is what’s known as a “masala movie,” a type of Bollywood flick that’s even more of a genre mashup than usual, with a crazy mix of melodrama, comedy, action, suspense, romance, and musical, just for starters — there is so much happening in this film. The tonal shifts can be a little jarring — one wrenching scene in which Anthony passionately beseeches Christ for justice after the death of his stepfather (Bachchan in full flow as the Angry Young Man — in this case, angry at God) is shortly followed by a supremely silly song-and-dance number with all three brothers in vaudeville disguises. Despite this tonal awkwardness and the kitchen-sink plot (kidnappings! car chases! blood transfusions! mistaken identities! snakes!), I loved this movie. I loved its cheesiness, I loved its tearjerking melodrama.

That’s true of all four of these films. I’ve gone on about the politics, but don’t get me wrong, that’s not the only reason to watch them. Their Bollywoodness is so wonderful. Other kitschy genres and styles have been defended as great cinema — Jerry Lewis comedies, 70s exploitation films, Douglas Sirk melodramas, Hammer horror. Bollywood should be no different.

And this is before I even get to the music! In Amar Akbar Anthony there’s a musical number set on various vehicles (a boat, a train, and a horse-drawn carriage) in which the three brothers woo their respective sweethearts; it’s so bright and sunny and effervescent and joyous, watching it I felt a warm, glowing feeling of genuine happiness. It actually improved my day.

Of the other films I watched and wrote up for the festival, one of the best was also a retrospective. This was The Devil Queen (Antonio Carlos da Fontoura, 1973). The late Milton Gonçalves (familiar to English-speaking audiences from Kiss of the Spider Woman) gives a jaw-dropping performance as the title character, a Black crime boss in Rio de Janeiro who happens to be a drag queen. The way Gonçalves inhabits this character is something else. The Queen is as fabulous and bitchy as she is ruthless and bloodthirsty. She switches fluidly from a tough, masculine register to a campier and more feminine one regularly depending on her mood; and she rules imperiously over a mob made up of a mix of thugs, fellow queens, and handsome young men for her to fondle. Writer-director da Fontoura and co-writer Plinio Marcos did exhaustive research in the underbelly of Rio in order to give their film an authentic feel in terms of slang and drag culture — much of which is lost in translation, no doubt, but it’s still so hypnotically lurid and sleazy and fun. Beautifully restored for its 50th anniversary, it’s saturated with tropical color and style. Beyond the fascination of the Queen herself, it features a terrific mix of noir and gangster tropes and campy comedy, with lots of dirty dealing and flowing blood, and a truly batshit torture scene that’s played for laughs but seriously disturbing nonetheless. (If torture is not your jam — and it really isn’t mine — consider this a trigger warning.) Someone wrote that The Devil Queen is like a cross between City of God and John Waters, and that’s really true. What struck me watching it half a century after it was made is not so much that it was remarkably ahead of its time — and it is, don’t get me wrong; it really feels like watching a contemporary film in every sense. But more important was the reminder that none of these things are new in our society, whatever the anti-woke jackasses think. Queer culture, drag, and gender bending have been with us forever — as have art and cinema adventurous enough to show them.

The best of the new crop of films I watched was Tora’s Husband, a drama by Indian filmmaker Rima Das. I wasn’t familiar with Das’s work before this, but she instantly jumped into my pantheon of contemporary filmmakers with this lovely, meandering, deeply moving feature. It stars her brother, Abhijit Das, as Jaan, a family man and restaurant and bakery owner in the Indian state of Assam who struggles to keep his business afloat amidst the aftershocks of the pandemic, while at the same time struggling to keep his marriage together. Tarali Kalita Das plays Tora, his wife, whose reserves of patience are deep, but running out.

I find it so interesting that Jaan is the main character, yet the title’s focus is on Tora and her relationship with him — one of many clues that the wonderfully detailed, complex, lifelike portrait of this man is painted from a woman’s perspective. Tora has the quietly devastating line of dialogue that best summarizes the story: “He’s a good person, but he’s not a good husband.”

Jaan is very dedicated to his family and his community. He clearly loves his two young kids; he went into debt paying his workers during lockdown; and he does things like buying soccer equipment for impoverished local kids. But he’s also a difficult man. He’s impatient, argumentative, and arrogant; and, like many small business owners, he’s a pushy boss who drives his workers nuts with his nitpicking and lecturing. To make matters worse his alcoholism is spiralling out of control in the wake of his financial troubles. He leaves his family every night to drink with his buddies, and he’s often hung over and maddeningly dysfunctional in the mornings. Over two-plus hours of watching Jaan’s day-to-day life — running errands in his SUV, arguing with creditors and debtors on the phone, hanging out with his kids — I started to feel a bit of what Tora must feel. I was very endeared to Jaan, but he drove me crazy too. Abhijit Das’s performance is marvellous; it’s difficult to remember at times that Jaan is not a real person.

The reason Tora’s Husband works so well is the great skill in its crafting. Rima Das handles almost all the behind-the-camera jobs — she wrote, produced, shot, directed, and edited the film, and all of her work is superb here. Despite its low-key, observational approach, which on paper sounds like so many other indies — yes there are scenes where “nothing happens”; yes there are plenty of shots of Jaan staring pensively into the distance — Tora’s Husband has real style, real impact, a real zing to its pacing.

The editing in particular is brilliant. It has a jumpy and subtly skewed rhythm that’s so engaging and even oddly thrilling. Scenes are often cut short a little earlier than you were expecting — for example a dialogue scene will leave you hanging mid-argument; or the next scene will begin mid-argument. During these brisk scene transitions it’s not always clear how much time has passed — sometimes it’s the same day; sometimes you become aware that days have passed and things have changed. It’s more of a series of vignettes than a straightforward story. This unusual rhythm and structure pulls you in, making you want to know more about these characters’ lives, and leaves you with a sense of unresolved conflict and continuous crisis, which well suits the story’s pandemic-era timeframe.

There are several scenes involving Jaan losing his temper with someone — a difficult customer at the restaurant, a friend during a binge-drinking session — and on these occasions, the camera is more static and the editing rhythm slows down, creating more tension as we watch Jaan unravel. All this artistry and finesse allows for an exceptional amount of engagement and emotion for such a quiet story.

I also appreciated the film’s refreshingly explicit references to COVID. In many of his scenes, Jaan is wearing a facemask — usually tucked under his chin where it doesn’t serve any purpose except to irritate him, a visual signifier of pandemic fatigue. Fleeting references to the social impacts of the pandemic occur in the dialogue over and over. In the scenes set in the city, the sound of ambulances is seemingly constant. That sense of ongoing disaster looming in the background is both eerie and relatable.

It amazes me to realize this, but looking back on the last three years, I don’t recall one other film that’s addressed the pandemic so directly. It’s like the film industry is in denial — along with our leaders and the mainstream media as they enforce “COVID normal” when this godforsaken thing is far from over. Tora’s Husband may be the story of one family, but it makes sure to situate that family in a community and a society that are in crisis. That social approach is so valuable and adds so much richness to this wonderful film. On a personal note, it also made me question whether I’m doing my best as a husband and father.

Two other films set in the Indian subcontinent are so remarkably similar in their broad outlines it felt deliberate, as if they were commissioned by the same agency for the same purpose. But the real reason for their cohesion is that war, oppression, and torture have sadly similar outcomes wherever they occur. The Winter Within (Aamir Bashir) and Sand (Visakesa Chandrasekaram) are both about militant rebels (Kashmiri and Tamil, respectively) who are released from military prison after being tortured and detained for years (by the Indian and Sri Lankan armies, respectively), and who struggle to fit back into their old lives while dealing with trauma and disability.

These are both valuable films for their efforts to educate audiences through fictional narratives about the very real impacts of occupation, state violence and genocide in Kashmir and Tamil Eelam. They are both beautiful films too — especially The Winter Within, with its stunning wintry landscapes in the Himalayan foothills (representing the frigid feelings of despair and trauma) and the gorgeous intricate handwoven creations of its protagonist Nargis (Zoya Hussein). If I’m being real, both films struggle to break free of the languid pacing and restrained tone that are typical of many festival films lately. That’s not completely a dealbreaker — I would call them both good films, and at a certain point you stop being analytical considering the gravity of the subject matter. The cast of Sand features several real survivors of the civil war, and The Winter Within concludes with documentary footage of Kashmiri families commemorating their disappeared loved ones. There’s a great deal of anger in both films — though Sand errs a little on the side of “both sides committed atrocities in the war,” a narrative I’m just not interested in when it comes to Sri Lanka’s genocidal war against the Tamil people.

One of the most memorable and definitely the most unsettling film I watched for the fest was Iranian writer-director Vahid Jalilvand’s Beyond the Wall. This psychological thriller is about a blind and depressed man (Navid Mohammadzadeh) who hides a fugitive mother (Diana Habibi) in his apartment after a protest by factory workers turns into a riot and a police officer is killed.

Because the Iranian New Wave set such a high standard for world cinema, and is especially known for its politically risky stories and nonlinear narratives, what you find in recent years is that some Iranian filmmakers are seemingly trying to top each other for intensity or weirdness. Such is the case here: you should know going into Beyond the Wall that the first ten minutes is an unbelievably harrowing scene involving the protagonist, Ali, trying to kill himself with a plastic bag in the shower. This scene made me want to get up and step back from the screen — it made me feel like I couldn’t breathe myself, and I thought it would never end. But it effectively establishes the tone of this very dark film in which nothing is as it seems. Jalilvand makes certain gestures towards the social realism that marks so many other Iranian films — the grime and mildew and dirty dishes in Ali’s apartment are so realistic it’s like we can smell them; and the riot sequence is so vividly shot and edited it feels like documentary footage — hands down it’s the best action sequence I’ve seen in any film lately. But after a while it becomes clear that Beyond the Wall is more concerned with dreams and nightmares than with reality. In particular, the more you see of the massive, dank, dystopian apartment building where Ali lives, the more you realize that something is off — it’s just a little too dystopian to be quite real. So Jalilvand’s commentary on real-life state repression in Iran — in a year of major upsurges in women’s resistance and labor militance — takes the shape of a warped narrative that makes Tehran seem like a Kafkaesque mindscape. It’s audacious, not always quite successful — especially for the relentless grimdarkness — but worth seeing for its eerily gripping screenplay and terrific acting.

Two more titles that didn’t grab me as much as the others round out my slice of the program. The most conventional of all the films I watched is the Mexican drama Radical (if you don’t count 70s Bollywood convention, which is so wild and kitschy it seems daring next to anything we’re used to in this day and age). Some readers might like Radical better than any of the rest I’ve mentioned, and I wouldn’t blame you (it won the audience award at Sundance this year). Directed by Christopher Zalla, it’s a tearjerker that fictionalizes the real-life story of an elementary school teacher in Matamoros who employs unconventional classroom methods to inspire the most impoverished and underperforming students in the country to dream big and do better. As a film it takes very few chances with the “inspirational teacher” formula, but it’s a solid entry in the genre, very well-made, and very appealing and touching once it has its hooks in you, especially for Eugenio Derbez’s fine performance.

The Chilean film Sorcery (Christopher Murray) has been described as “decolonial folk horror.” It’s based on the true story of a witchcraft trial in the 1880s on the island of Chiloé. The father of a 13-year-old native Huilliche girl is brutally murdered by the German settler who employs her, and she turns to a local native animist cult for supernatural retribution. If that synopsis grabs you, then you probably won’t go wrong with this one; though I found it a bit too restrained and implosive and just not scary enough compared to its folk-horror influences (especially The Witch).

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!

Feature image: Amitabh Bachchan in Deewaar (Yash Chopra, 1975)

One thought on “Sydney Film Festival preview: A deliriously good Amitabh Bachchan retro, plus other highlights”