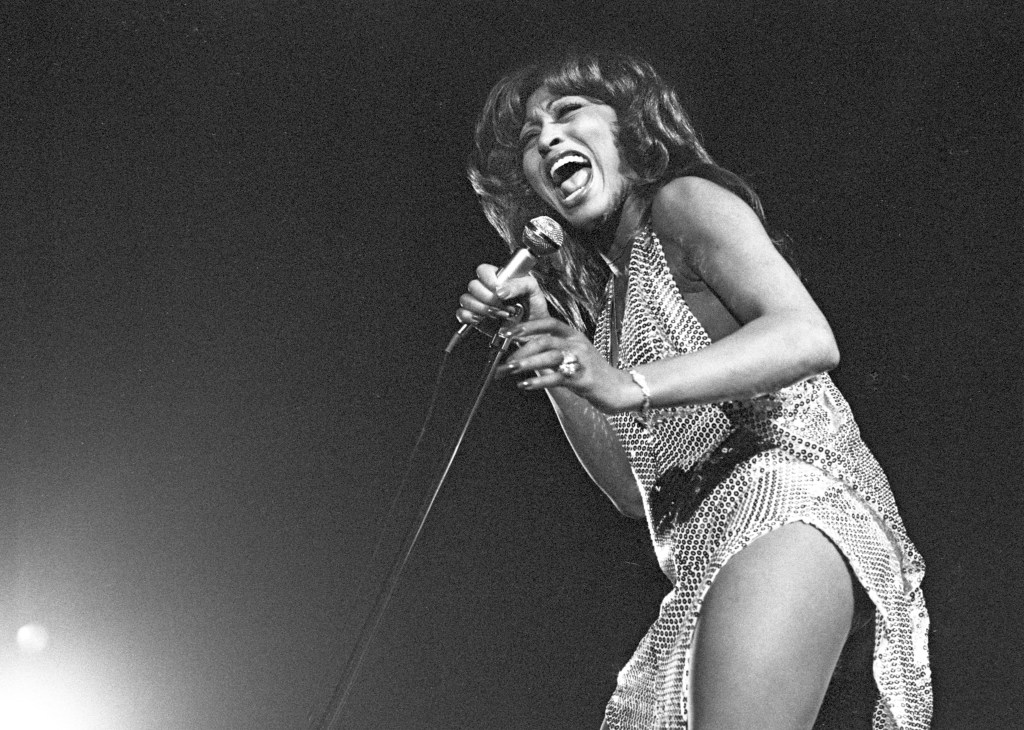

There were two things I noticed about the reactions to Tina Turner’s death last month. First, there was a general agreement that even though she was 83, it still felt tragically early, way too soon for her to go. She was one of those artists who seem so filled with life and energy and passion, who seem to embody life itself. It didn’t seem possible that she could grow old or get sick and decline.

It also seemed that most obituaries and tributes could hardly contain all of her accomplishments and all of her brilliance, like the sheer force of her was erupting off the page. Her career is just astonishing if you pause to consider it. She was the Queen of Rock and Roll for 60 years. She started singing as a teenager in the 1950s when the form was still in its infancy. She toured relentlessly and honed her craft with Ike Turner for decades while creating some of rock’s greatest anthems. She taught Mick Jagger how to strut. Through the sheer immensity of her genius she made sure the music industry and press couldn’t forget about Black women in rock through the long years when almost all the attention was on white dudes.

Then, she had one of the greatest comebacks in music history. She dominated pop charts, music video channels and big stages around the world, and became one of the most beloved public figures of the 80s.

But also, she was was if anything most revered as a survivor, who practically all by herself made the issue of family violence against women, and Black women in particular, acceptable to talk about in public.

She was all of that. But you also can’t forget that Turner, with her incredible magnetism and performative skill and soul, was also a brilliant actor who never got enough chance to shine on the big screen.

Thankfully we have one star performance to always remind us of her range and genius, and that is of course in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. The word iconic is overused but it applies in every sense to Turner’s role as Aunty Entity in the third entry in George Miller’s groundbreaking postapocalyptic film series.

I was a fan of Turner’s before Thunderdome was released in the summer of 1985, when I was 14. As an 80s kid and avid pop consumer, Turner was for me what Diana Ross or Aretha Franklin were for earlier generations. But I was also a sci-fi nerd and a massive fan of Mad Max, ever since The Road Warrior (or Mad Max 2 as it’s called in Australia) exploded onto American screens in 1981. (I love Mad Max so much I wrote an essay about the politics of the series for Jacobin.)

Turner’s presence in Thunderdome was huge for me, worlds colliding in the best way, and it cemented my love for her.

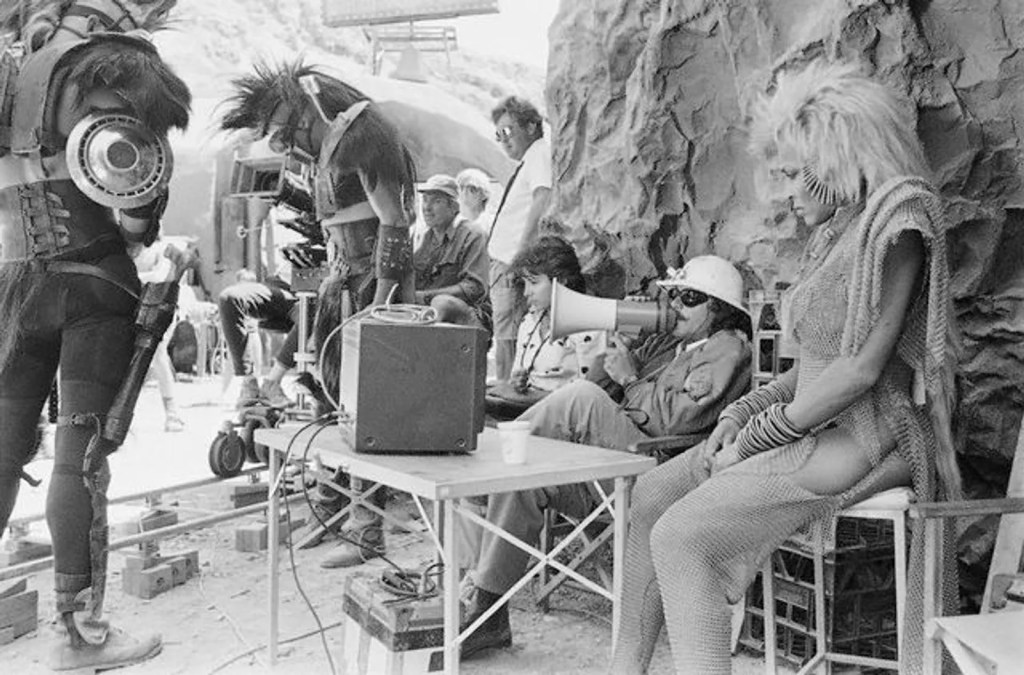

The image of Aunty Entity, with her outrageous chainmail costume, her fabulous bleached-blonde lion’s-mane punk hairdo, her coil-spring earrings, her handheld crossbow, and her imperious poise and grace, is the embodiment of postapocalyptic badassery, and remains fresh in the collective memory after decades. Even more, Turner’s radiant charisma and nuanced portrayal ensured that Aunty would be an unusually sympathetic baddie. She’s one of the most unforgettable screen villains of all time.

Aunty had a huge impact on the series, and on the genre. It would be years, decades even, before representation of women and Black people became a hot topic and started to gain traction in the film industry and specifically in science fiction. In the sci-fi landscape of 1985, Turner’s Aunty Entity was like a cool drink of water in the brutal wasteland of the film’s story.

The fact that the songs she recorded for the soundtrack were massively successful — and absolute bangers to this day! — only adds to the legacy of her involvement in the film.

It was a pretty brave move for Turner to tackle this film in the first place — a sequel to an Australian postapocalyptic movie, one that was critically acclaimed but still relegated to cult status, and mainly known for its spectacular stunts. Think about how different the entertainment business was back then. Nerd culture wasn’t anywhere near as mainstream as it is now. There was Star Wars and Star Trek, and a few other popular franchises, but they didn’t dominate entire sectors of the film industry the way Marvel does now; there was no such thing as prestige sci-fi TV series like The Last of Us; A-list talent hardly ever got involved the way Cate Blanchett or Michelle Yeoh or countless others do now.

In late 1984 when filming on Thunderdome took place, Turner was neither washed up, nor an over-the-hill veteran looking for new challenges. She was right in the middle of mounting her historic comeback. Her Private Dancer LP had been released just a few months earlier, and “What’s Love Got to Do with It” was still on the charts when Turner was on location in the remote mining town of Coober Pedy, South Australia.

It’s worth noting that Australia is a long way from anywhere (trust me, I live here), and would have seemed even further away at the time given the differences in air travel and communication. Mad Max movies are famously difficult productions, with their desolate settings and dangerous stunts. Imagine a 45-year-old rock star leaving everything behind at the height of her resurgent fame in order to travel to a hot, dusty film set in the Australian Outback, don chain mail and take on the part of a postnuclear warlord.

But Turner knew exactly what she was doing. She’d turned down numerous acting roles over the years because “there were no parts for Black women” that weren’t “really street, really hooker,” as she said in a 1986 interview with Italian magazine Luce Cinecitta. I really admire her stubbornness and pride in holding out like this when others would have accepted whatever opportunities came to them. And her perspective is very interesting in context of the current moment. The eternal cry of the anti-“woke” jackasses is that “woke” representation is an overreaction to a made-up problem, but if you listen to Tina Turner talking about it in 1986 you can see that it was very much an issue back then too.

Turner also famously turned down the part of Celie Harris in Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of The Color Purple (which ultimately went to Whoopi Goldberg) because the role of a Black woman who endures violence at the hands of her husband was too much like her own life. “I mean, I’m talking always to the press about my life and now to do a movie?” she said in that same 1986 interview. “I’m just dragging myself down. I’m trying to forget the past because it’s done. It’s over. I finished that part of my life, and I’m not going to do a part that will remind me of what I’ve lived already.”

What Turner really wanted was to be a “mad woman” onscreen, and she was especially a fan of strong women characters in sci-fi films like Alien and The Terminator. “It is the warrior woman parts that I want,” she said. “I want physical parts. I want to drive the machines, to do the fighting. I want to be physical. I still need that excitement.”

George Miller says Turner was the only actor he seriously considered for the part of Aunty Entity, and it’s easy to see why. Aside from her outstanding performance, her commitment to the role is legendary. She actually shaved her head so the punk wig could fit her. She insisted on doing some of her own stunts, including driving her own vehicle in the climactic scenes (which meant the crew had to convert the vehicle’s drive to automatic, since Turner couldn’t drive manual). All involved have reported that she was a team player on the set, and a trooper during the long, uncomfortable days and nights in the desert. “There was absolutely nothing of the diva in her,” Miller says. He tells a story about how on the first day of production at Coober Pedy, Turner saw that the cast and crew were suffering in the extreme heat, and she went to Miller and insisted that he “force water on them.”

“You could tell she was someone who knew how to get through tough times,” Miller says.

This is probably a good time to say that I love Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. It’s a flawed film, but nevertheless a great one if you ask me, and there’s no other film like it. It’s widely considered the weakest Mad Max movie, and I suppose I agree, but that’s not saying much — I love all four entries in the series. I love how different they all are, as if each sequel is really a reboot; and each one captivates me all over again whenever I happen to watch it.

Thunderdome represents Miller and co-director George Ogilvie’s efforts to leave behind the exploitation and minimalism that had previously defined Mad Max and transform it into a very 80s Spielberg-like adventure. The thing is, they largely succeed at this (I’m a Spielberg apologist so it works for me). Miller is worthy of the comparison to Spielberg; he’s a genuinely great director who, while not exactly flying under the radar, is somehow still underdiscussed despite all the classics he’s made.

It’s true that the Lost Tribe of children are annoying, in an Ewok sort of way, or like the Lost Children in Spielberg’s own disastrously poor Peter Pan flick, Hook. Their shallow, cliched indigeneity doesn’t help either, especially in a series that almost completely excludes First Nations people in its vision of the Australian postapocalypse. There’s something kind of Burning Man about those kids (not in a good way). And it’s true that the climactic chase is a letdown. More a series of visual gags than a proper action sequence, it has nothing on the nailbiting epics in The Road Warrior and Fury Road, and it gets a little too cute with the slapstick and the Buster Keaton references.

But there is so much to love here too. Bartertown, the film’s dystopian society that represents all the violence and exploitation of the old world rebirthing itself in the wasteland, is a fabulously textured and imaginative creation that makes for a powerhouse first act of the film. The medieval feel of it all, and all the detail in every frame that’s so wild but also so weirdly plausible — the camels! The Atomic Cafe! The preacher/huckster guy! Ironbar’s kabuki mask! It’s ingenious that this place is run on methane extracted from pigshit; and the heaven/hell analogy, with the dank pig-factory underworld below, Aunty’s airy dwelling above, and the purgatory of the chaotic, debauched streets in between, is a potent visual scheme. As Australian critic Adrian Martin writes, Thunderdome is “an essay on the nature of civilisation — with Max still the archetypal wanderer who allows us to traverse and compare different modes of social life.”

Thunderdome itself is one of the few really original concepts for hand-to-hand combat in action-movie history; no wonder it’s become a lasting pop-culture trope. That scene, with its dizzying dimensionality and its nightmare spectacle of state-sanctioned violence, is truly indelible.

Throughout the film, the fluid, constantly moving Spielbergian camera is still thrilling. Maurice Jarre’s melodramatic score is terrific even if it’s corny. Despite the dated elements and missteps, it’s still a very affecting story. Miller, Ogilvie and the cast are so good at making you care for each character (even the annoying kids), making the suffering they’ve been through seem real despite the outlandish setting. The moment when Max sees Blaster’s unhelmeted face is still one of the most wrenching in any film. The climactic scenes involving Max’s sacrifice, and the denouement showing the Tribe Who Left arriving in the blasted-out ruins of the Sydney CBD, still bring tears to my eyes.

A take I saw repeated a few times after Turner’s death is that she’s the best thing about the worst Mad Max movie. Indeed she’s the best thing about it, but I prefer to say she elevates what would have been a good movie anyway.

She literally elevates it in that still-astonishing scene when she first appears. In the first 10 minutes of the film, Miller and Ogilvie expertly build the suspense as Max stumbles onto Bartertown and manages to negotiate a meeting with the boss over a stolen vehicle. Soon he’s riding a lift to a penthouse perched above the teeming filth of the settlement, its soft billowing curtains a weird juxtaposition with the leather and metal of the Mad Max milieu, its arched roof deliberately invoking Sydney Opera House, while somewhere inside a saxophonist incongrously plays a mellow jazzy tune.

It turns out the boss is Turner, of course, and she instantly makes an impact with her resplendent charm, her wickedly crafty smile, her lively chemistry with Mel Gibson, and her deadly “audition” for a hired killer. She almost glows with the joy of inhabiting this character. And there is that Afropunk costume, designed by the great Norma Moriceau (RIP), who, through her work on The Road Warrior and on this film, is almost singlehandedly responsible for what we think of as the look of postapocalyptic cinema.

Aunty’s costume still amazes me. Like many great sci-fi costumes, it doesn’t seem physically possible; it seems to defy gravity. It’s both regal and campy, both ethereal and warlike.

Like the costume, Turner’s performance also deftly mixes camp with something much more substantial. She savors every line of dialogue: “But how the world turns! One day, cock of the walk. Next, a feather duster.” Her line readings are something else: soulful and melodious, but also threatening… but also weary and vulnerable. Her utter sincerity amidst the batshit events of the story is exactly what’s needed, giving it extra depth and resonance.

Take the scene in which Aunty watches on as Max faces the Wheel of Justice. Without a single line of dialogue, Turner communicates so much with her eyes and her facial expressions. Does she want Max to die? Does she want him to be reprieved so he can join her as an ally, or perhaps even more than that? It’s not clear but the enigmatic tension is powerful.

Balancing these more introspective bits are those when Turner gets to unleash her rockstar mode, like the — forgive me — iconic moment when she howls with outrage and leaps down onto Thunderdome’s floor to assert her authority over the grumbling crowd: “What’s this? What’s this?!”

Like so many other characters in the series, Aunty’s trauma is believable and palpable. We can only imagine all she’s been through; she alludes to it but only vaguely. “Do you know who I was?” she asks. “Nobody. Except on the day after, I was still alive. This nobody had a chance to be somebody.”

The fact that she’s a Black woman adds great poignance to this implied backstory — how much harder she had to fight to survive and achieve her power. We glimpse this in the scene in which Master humiliates her with his embargo. It’s still such a painfully raw and uncomfortable scene, and Turner’s reactions make it feel real.

Fury Road, Miller’s masterpiece, is rightfully lauded for foregrounding themes of women’s oppression and liberation; but 30 years before Imperator Furiosa redefined the saga, there was Aunty Entity.

I’m not arguing that Aunty is some kind of girl boss, someone to look up to. That would be reductive. She does awful things — she oversees horrific exploitation of convict labor, she enforces a brutally arbitrary justice system, she ruthlessly orders the murder of a mentally disabled man. If we’re to take the character seriously on her own terms, she actually shows the shortcomings of the girl-boss narrative.

But fictional villains are always better when they are human, when we can feel a certain amount of compassion for how they ended up like this. And the Mad Max series has always explored the morally uncertain things people do to survive. Furiosa is a hero in the narrative of Fury Road, but who knows what evil she’s done in the past, in her position as Immortan Joe’s war captain?

The same question applies to Max of course. The symmetry between Max and Aunty — the traumatized past, the moral ambiguity — is directly addressed by her: “Ain’t we a pair, Raggedy Man?” One of the weaknesses of the film is that it doesn’t further explore that symmetry — not to mention the great chemistry between Turner and Gibson — by letting the pair interact more than they do.

Aunty may be a villain, but she’s so relatable and inspires so much empathy that she stretches the definition of the term to its limits.

In case you’re thinking that Turner’s history as a survivor must have informed the character of Aunty, Miller is here to tell you that you’re right: “You needed to have seen a lot of rough times and you weren’t diminished by it,” he says of her performance. “Tina embodied that. Everybody knows her story and she just carried that power with her.”

All this is why I think Turner was pivotal for the series, despite the fact that she appears in only one film. She brought gravity to Mad Max, and gave it more relevance in popular culture, which helped transcend the middling reviews and carry the franchise through the long years before Fury Road. She pioneered representation for women in the saga, and established the multicultural, internationalist, even borderless feel that was expanded on in Fury Road. This only makes sense: Australia is a very multicultural nation; not all the survivors of an apocalyptic event would be white with Aussie accents. But on the other hand it doesn’t even have to make sense that Turner (and Charlize Theron, and Tom Hardy) weren’t or aren’t Australian, because the further the saga takes the narrative into the future, the less it’s even about Australia, and could be set anywhere, or nowhere.

Finally, Turner’s musical contributions made a huge difference too. “We Don’t Need Another Hero” was a worldwide hit; it went to number two in the U.S., and number one in Australia. “One of the Living” wasn’t quite as big a hit, but it won the Grammy for best female rock performance.

“Hero” is such an unreasonably good song. Yes, it epitomizes a certain kind of 80s cheese — a Mad Max sequel wouldn’t feature a track like this nowadays, would it? But it’s exquisite cheese, and perfect in context. Songwriters Graham Lyle and Terry Britten (who also wrote “What’s Love Got to Do with It”) deserve the Ivor Novello Award they won for it; and Britten’s lush, funk-inflected, whisper-to-crescendo production is ace.

But between the two songs, “One of the Living” is my jam. After 38 years, that one (written by Holly Knight, who appropriately enough also wrote “Love Is a Battlefield”) makes my hair stand up every single time I hear it. The amazing synth-rock arrangement, as if Depeche Mode decided to make glam metal; the way it starts out with those deep, tribal drum-machine loops and those eerie keyboards that sound like the world is ending; and the way it builds and keeps building. I’ll never forget the first time I saw the film and the exhilarating effect of it playing over the opening titles.

Two things in particular jump out at me when I hear these songs now: first, the level of passion that Turner pours into both of them. A singer of her caliber could have left it in cruise control for a movie tie-in, the way Phil Collins or Bob Seger would, and the hits would have been just as big, but Turner blows the roof off — it’s nuts. I honestly think in some ways she’s at her best here. It’s more proof of her commitment to the whole project.

The other thing I can’t get over is what she’s singing about. A lot of singles from movie soundtracks are safely generic, lyrically speaking — think about how “The Power of Love” or “Footloose” could be about anything instead of time travel or rebelling against fundamentalist theocracy. But “We Don’t Need Another Hero” and “One of the Living” are beautifully specific. They are absolutely about surviving in a postapocalyptic wasteland. It kills me when, on “One of the Living,” Turner sings, Can’t stop the pain of your children crying out in your head / They always said that the living will envy the dead. This was actually played on top 40 radio! And I love that You’ve got ten more thousand years to go addresses how long it would take to rebuild civilization after a nuclear war. There’s so much in that line, especially the way Turner delivers it, with such conviction and in this chanting intonation that could be described as “Goth soul.”

“Hero” is also great for how it undercuts the whole idea of heroism, especially in context of the hypermasculinity of 80s action movies — and, more broadly, militarism in the Reagan era. The subjects of the song are the children who’ve survived armageddon (it’s ironic that the actor who plays Aunty sings from their perspective), and they are understandably not interested in a warrior to champion them; they want nothing to do with the violence and aggression that got them into this in the first place. They don’t want to go “home” — back to the world that was — they want a new kind of society. This anticipates the slogan raised by the Five Wives in Fury Road, “Who killed the world?” In the guise of an action-movie anthem, it’s a moving antiwar and antinuclear protest.

That kind of social conscience is baked into the saga, from the angst over nukes to Fury Road’s feminism. I just think it’s wonderful that Turner was there to give that social conscience a voice, and take it to the top of the charts at the height of the 80s. It’s just one more thing to celebrate about a wonderful collaboration amidst an unparalleled career.

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee, subscribe below, and share this article!

Feature image photo credit: Tina Turner in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (George Miller & George Ogilvie, 1985)