This is a reader-supported blog. If you like what you read, consider buying me a coffee!

I don’t know how to break this to you, but one of the most interesting and cinematically adventurous films of the year is a franchise IP blockbuster that was made explicitly to sell dolls.

I didn’t intend to write about Barbie going in — it’s so discoursey right now, enough pixels have been spilled about it, and honestly I’m busy and have other things to write. But the night I saw it, I compulsively started writing notes about the film’s politics in a gmail draft, and before long it was article-length. So here we are.

Rather than a full-blown review or essay, I’ve decided to make this into a Jenny Nicholson-style internet-friendly list. If I set about writing a proper essay it would be overwhelming, because there’s a lot going on in this film. Sticking to a few points about Barbie’s lively and contradictory politics is the best way to impose limits on myself while still touching on a lot about the film.

So here we go — floating right down into this like Barbie floats from her house to her car:

1. Cinema — This is the first and most important thing about Barbie for me, and I need to foreground that before I get into the politics, because its cinematic strengths color my outlook on its themes.

Greta Gerwig is one of my favorite working filmmakers — I would rank both Lady Bird and her adaptation of Little Women among the very best films this century. But when Barbie was announced, and even after seeing the trailer several times at the movies with my kid, I was dubious. I assumed Gerwig was more or less a hired gun on this project, and I saw two possibilities: either her style would be subsumed by the franchise behemoth, or the whole thing would be an unwieldy mess like Robert Altman’s Popeye or Tim Burton’s Batman.

I was wrong about all of this, and should not have doubted Gerwig. Barbie is easily the boldest and most audacious franchise film since Black Panther, if not ever. Its production design is a triumph; there’s never been a film with design quite like this, and if there’s one thing it deserves to be canonized for, it’s that. The lengths Gerwig and her collaborators went to in building this entire dream world on a soundstage, instead of doing it with CGI; the way most of the special effects are done practically, in-camera, such as the amazing moving landscapes; the incredible sets, props, and costumes; and the way Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography captures it all in what seems like old-fashioned Technicolor, which is only appropriate given the overt tributes to Golden Age musicals.

The production design is intrinsic to the themes: Barbie is heavily influenced by The Wizard of Oz, The Truman Show, The Neverending Story, and other classics in which a fantasy world collides with reality (or “reality”), and the characters grapple with which world they belong in. Like those films, Barbie’s fantasy world isn’t realistic at all; it’s very fake and kitschy, and that gives it an amazing hyperreal quality — “authentic artificiality,” as Gerwig calls it.

The screenplay, written by Gerwig and partner Noah Baumbach, is terrific. The dialogue crackles. The blizzard of self-referential jokes and pop-culture gags and the absolutely batshit intertextuality are everything they should be. It is a very, very funny movie; I laughed more than I’ve laughed in any movie recently.

I just feel it’s important to point out these simple pleasures about Barbie, because people are taking it so damned seriously. It’s funny! It’s smart! It looks great! It’s a lot of fun!

The characters are great too. Ryan Gosling is so good as Ken he’s been accused of stealing the show, but I would say Margot Robbie’s starring performance is too substantial to let that happen. Both accomplish something pretty impossible: juggling the “plastic” nature of their characters and the wild kitsch with the real and troubling human emotion that’s bursting out of them. It’s a very touching, very human film. Gerwig balances comedy, satire, and sentiment as well as any filmmaker.

It does falter at times, and it sags towards the end as the sentiment congeals into mush during one climactic scene in particular.

One thing I’ve noticed is that critics of the film will often say they thought it was poor on a cinematic level. I’ve seen several suggestions that it was badly written. Say what? I have to wonder if they saw the same film I did — maybe they accidentally watched an animated Barbie movie on Netflix? Gerwig and Baumbach are two of the greatest screenwriters alive and I assure you it shows.

I think what’s happening is that some people who don’t approve of the politics feel it has to be a bad movie because of that, so they just make it that way in their minds. This may be a bit mean but it reminds me of what Jenny Nicholson says about Last Jedi haters: “I feel like some of these people have never watched a movie before.”

2. Prescriptive takes — When it comes to popular culture, a lot of left-leaning people feel the need to weigh in as if they were assessing political policy instead of consuming entertainment. This is especially true when the discourse becomes this white-hot (pink-hot?). Everyone has to have their take on this movie about dolls.

Whether or not anyone in the audience really thinks this way, the dichotomy goes like this: is Barbie a brilliant pop manifesto for girl power that’s singlehandedly inspiring a new generation to question the patriarchy? Or is it a terrible setback that’s reifying women’s oppression through unhealthy feminine ideals and consumerism?

I think you can enjoy a film with one part of your mind, and critique its politics with another part. A Hollywood blockbuster is the collaborative effort of hundreds, and is by its nature trying to be many things to many people. A movie can have both good and bad politics — that’s certainly true of Barbie in my view — and you can hash out those politics while still appreciating it as entertainment. Not many films can be as politically uncompromising as Reds or The Wind That Shakes the Barley (and even they contain their share of things to debate).

The Barbie Culture War reminds me of the feverish discourse around Black Panther. Remember how it either had to be a great watershed for Black representation and Afrofuturism, or it had to be insidious corporate-backed propaganda for the CIA and the institution of monarchy that duped audiences into believing revolutionaries are villains? It couldn’t be merely problematic; it couldn’t be an enjoyable Hollywood popcorn movie with fabulously realized Black characters and lots of fascinating and contradictory things to say about Black oppression and Black liberation.

More importantly, a lot of commentators seemed to miss that the very existence of revolutionary ideas in this movie, even if they were voiced by the villain, said something exciting about the growing acceptance of these ideas in the mainstream.

When a film makes me think about politics, I get excited — even if the politics are messy or lacking. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse contains these kinds of contradictions. It’s wonderfully nuanced and sensitive on questions of racial identity and gender; but both of its protagonists have cops for dads, and that’s problematic, especially post-George Floyd. I don’t feel the need to take it to task for that (“Superheroes are cops!”). Copaganda is pervasive in our mass entertainment because it’s pervasive in our society; that’s not Spider-Man’s fault. I’m not expecting a call for abolition in an animated superhero movie. Instead I find it exciting that it felt the need to address BLM at all, and that, despite being soft on the police overall, it includes some surprisingly uncomfortable points about police violence — because the movement has raised mass consciousness to that degree.

3. Consumerism (selling dolls) — Barbie is bad because it’s selling toys! But also the entire movie is about how selling toys is bad! But also it’s still selling toys anyway!

It’s rather obvious that Barbie is all about marketing for Mattel, and yet some commentators mention this breathlessly, as if it’s breaking news, or as if that’s all there is to mention.

It would be silly to downplay the corporate tie-in. And yet the film is undeniably a stinging, provocative satire of consumer capitalism and the whole concept of Barbie. A lot of critics want to dismiss the satire, as if the jokes are there only to deceive. But you wouldn’t have a cinematic text this rich if it was only about marketing — you wouldn’t have a young girl violently smashing a doll’s head against a table in a visual tribute to 2001: A Space Odyssey in the first scene. If it was only about marketing, a straightforward adaptation along the lines of The Super Mario Bros. Movie would have been a lot easier, and it would have made the same mountain of money.

To be clear I have little interest in other current “IP movies” — I can’t imagine wanting to see the one about Nike (ugh). Yes it’s a dismal trend. Gerwig and her sublime vision are the only real reasons I’m even engaging on this one.

Does Barbie overcome this cognitive dissonance? I think it does part of the time — Gerwig really gets on top of the branding with her wicked satire, especially in the first half, and you wonder how this film even got made. But then it creeps up on you, especially during the groan-inducing scenes featuring Barbie’s real-world creator, Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler (Rhea Perlman). These scenes are not only corny, they’re jarringly different in tone from the rest of the film, and honestly it’s like they were imposed by the company. Suddenly it feels like a great big ad again, albeit a very sophisticated and self-effacing one. Which is a downer for sure.

But the only time I was outright offended by corporate tie-ins in Barbie was during the “real”-world scenes involving cars, which feature several obnoxious product placements for GMC. I’ve always hated this — it’s one of my pet peeves about the MCU, all those laughably bad placements for Audi that completely break the spell of the story. It’s the same here. One of the dumbest things about this practice is how obvious it is that they aren’t allowed to show the cars as used or scratched-up in any way; they always have to be gleaming and brand-new like a TV ad. Compared to this the stuff about the dolls is practically punk.

A lot of good movies are about selling stuff. Toy Story was arguably just Disney greenlighting a film they knew would sell a lot of toys (even more plainly the case for the sequels).

Selling toys doesn’t have to be the end of the story. He-Man and the Masters of the Universe was quite cynically all about selling toys; but since the 80s it’s spawned a lovely, kitschy, very gay pop-culture fandom. (As it happens, Barbie dolls have historically been co-opted by LGBTQ+ folks in similar fashion.)

Beyond this is the simple fact that all Hollywood movies are made for commerce. If they aren’t about selling toys, they’re about selling movie tickets and expensive junk food and Netflix subscriptions. Billionaires are profiting either way (this has been made much more clear during the writers’ and actors’ strikes).

Then there’s the question of ideology. No movie is free of ideology; every movie is selling us a view of the world. Barbie is selling toys, and a problematic brand of feminism; Oppenheimer is selling liberal imperialist ideology about nuclear weapons during a time of increasing militarism towards China. Which is worse?

Now if this entire conversation is distasteful to you, I get it. I wouldn’t try and convince you to see Barbie if you’re just not into franchise flicks or this kind of lurid pop culture. I have my own boundaries with corporate sponsorship; I loathe it in the music scene. With blockbuster movies it doesn’t bother me as much, maybe because I’m a longtime fan of Marvel and Star Wars and Pixar and other franchises with completely compromised corporate interests.

I don’t mean to be cynical or nihilistic about this; I passionately want to live in a world without capitalism (and much of my time is dedicated to organizing for that very thing). It’s just that there isn’t a 1:1 relationship between my taste in movies and my revolutionary politics. Certainly my politics color how I view and interpret films and other art. But also I take in Marvel movies and pro sports for the same reasons lots of other people in the working class do — because it’s fun, and a great way to blow off steam after a long day in this shitty crumbling system.

As a Marxist I avoid moralizing about consumption of mass entertainment. Movies may communicate ruling ideology, and that ideology may need critiquing and resisting; but mass entertainment doesn’t constitute brainwashing like many vulgar leftists argue.

To quote my comrade Maria Chanan in her brilliant recent talk on Marxism, consumption and pop culture:

Some on the left oppose consumer society for creating false desires in people instead of ‘genuine needs.’ In this view the working class is completely manipulated — consumption zombies with no ability to think for themselves. We are seen as dupes who are easily swayed by big advertisers to spend tons of money on useless things. While we do need to acknowledge that a great deal of commercial culture is manipulative and of course filled with propaganda, the notion of the working class as a purely passive force unable to ever see through that is pretty unsocialist and counter to our political beliefs.

4. Satire — Barbie is not exactly breaking new ground in being meta and weird in the context of franchise entertainment — kids’ movies have been doing this for years. A favorite of my family’s is SpongeBob: Sponge Out of Water (2015), a 90-minute whirlwind of multimedia, meta jokes and dank pop-culture references. Barbie is not even innovative in selling toys while mocking consumerism, as the Lego Movie franchise shows.

But Barbie sets itself apart by how far it’s willing to go in deconstructing the whole idea of the marketing of toys, and the role they play in girls’ lives especially. In her opening monologue, the narrator, Helen Mirren, tells us that the residents of Barbie Land have only fooled themselves into thinking they can change the world through positive images of women’s empowerment. Soon Barbie is questioning her own exisitence and thinking about death (her faux pas in the nightclub is already iconic for a good reason: it is truly brilliant). In queasily farcical scenes that take real risks in acknowledging Barbie’s impact on body image, her horror of cellulite and of her suddenly flat feet — in other words her internalized sexist beauty standard — is presented as a problem. When Barbie finds herself in the “real” world, she discovers to her dismay that she’s the product of a corporation that sells feminism and empowerment to little girls for profit. The scenes featuring Will Ferrell in a pink-scenery-chewing performance as the Mattel CEO, at the head of a board table surrounded by only male executives, are ripe with implications about the company and all companies.

The satire is especially potent in tandem with the film’s visual inventiveness. More importantly, the satire never gets in the way of the fun and vice versa.

It all feels bracing, even subversive, while it’s unfolding; but like I said, before it’s over we can see through it. Mattel has agreed for Gerwig to mock them, almost like a king allows a court jester to do so. She can foreground the company in her narrative and savagely critique their entire enterprise, because they know it won’t actually impact their profits. In fact it lends them legitimacy, to be seen as taking the piss out of themselves this way and impressing critics and savvy parents. Corporations are increasingly tactical about these things lately. That’s insidious, and it’s a reason to be uneasy about Barbie.

I don’t have an argument or a solution here, but I feel this is important to emphasize: I wasn’t expecting anything else from Barbie.

I wasn’t expecting The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie; I wasn’t expecting satire that actually challenges our social relations. Yes, it’s weird and dystopian that Gerwig, with her monumental talents, is wrapped up in this insanity, but this is capitalism in 2023 as it groans under the strain of the permacrisis, and she improbably finds a way to make it worthwhile.

5. Is Barbie sexist? — This is a big question, and considering the film is explicitly feminist it’s an interesting one. There are two main components to this argument:

- The doll is sexist

- The film legitimizes the doll, therefore it is sexist

The first point is pretty inarguable; the existence of Barbie dolls represents so many things wrong with our society. The dolls have been proven to negatively impact girls’ self-images.

The second point is more complicated. This takes us back to whether mass audiences are so easily manipulated. Yes it’s an ad for the toy company (however satirical), we’ve established that.

But in practical terms, what messages are audiences really coming away with? Are they resolving that being feminine and wearing pink is the way to go? Do we think Barbie is keeping young women from organizing Starbucks unions or fighting for abortion rights? Is it just about the dolls?

If we consider that the target audience is girls and women aged 14 to 34 (the film is rated PG-13 and not really for young kids), this idea of doll propaganda starts to break down. Those generations know about satire, they know about irony, they know about kitsch. They know about Me Too and class struggle in this time of crisis. They are extremely media-savvy, and know how to engage with a text in multiple ways. They can enjoy the memes or wear a pink outfit to a screening without betraying their principles or losing their sense of self. It’s a shallow, condescending, rigid assumption that they are being bamboozled en masse.

And as a comrade pointed out, it’s disingenuous for critics to say the film is legitimizing the dolls, when its critique of the dolls is deeper and more interesting than their own.

If you see Barbie as troublesome or compromised with regard to the dolls, you certainly have a case. But I don’t think you can flatly state it’s harmful to the women’s movement. If anything, it’s nudging audiences somewhat to the left, by raising issues of gender inequality and patriarchy in a hugely popular movie. As a social phenomenon this is plain to see and it outweighs the stuff about the dolls themselves. One small measure of this is that it’s set off a trend of women breaking up with their bad boyfriends. Barbie has enraged the right wing and anti-“woke” jackasses for a reason. Even just provoking widespread debate about whether its feminism is of any use or not is a good thing.

I’m not making a case that these things are always up for dispute. There are films that are inarguably sexist. Fatal Attraction. Last Tango in Paris. M*A*S*H.

Jeanne du Barry, the latest by French filmmaker Maïwenn, is sexist simply because it stars Johnny Depp, and is therefore a disgusting attempt to rehabilitate an actor who has become a symbol of misogyny and the backlash against Me Too. Please don’t support this movie.

With Barbie, I think it’s fine to take masses of young women at their word that it’s positive and inspiring for them, whatever we think of it.

Barbie reminds me of the clashing views over the careers of female pop stars like Madonna, Britney Spears and Taylor Swift. Was Madonna cynically selling herself to a sexist media? Was it something much more empowering and liberatory? Can both be true? That debate has never been settled, and it basically comes down to whether you like her music or not.

The gargantuan scale of Swift’s popularity points to broader problems: the way the media apparatus upholds a certain kind of woman as a feminine ideal while marginalizing others, for starters. She’s almost like a living Barbie, you could say. And last I checked she’s approaching billionaire status, which would mark her as our class enemy if you want to go there. But for many young women, Swift also represents a certain ideal of freedom and joy and sisterhood that arguably transcends the artist herself. To make a political case that Swift is inherently damaging would just be a quick way to pointlessly alienate vast audiences of young women who fill up stadiums around the world for her, and whose taste in music probably doesn’t have much to do with their radical potential or lack thereof.

6. Feminism — I agree that Barbie’s view of feminism is very limited and confined to the political mainstream — bourgeois feminism as we Marxists call it. The revolt of the Barbies against the patriarchal dictatorship imposed by the Kens involves a twofold plan: deprogramming all their fellow Barbies by teaching them feminism and ridding them of their feelings of inferiority and subservience; and distracting all the Kens in order to retake control of the government of Barbie Land and restore the constitution. While the execution of the plan is clever and funny (the bits about hoodwinking the Kens by allowing them to mansplain The Godfather and Pavement are painfully hilarious), the political ideology behind it, the belief that women’s problems can be solved in the halls of government, is dubious to say the least. This is the essence of girlboss feminism and there’s a reason it’s increasingly rejected by young women these days. It’s no doubt why so many leftists compare Barbie unfavorably to Hillary Clinton (which is just funny to me because it’s like, did Greta Gerwig destabilize Libya?).

Perhaps worse is Barbie’s assertion that simply by speaking about the problem of patriarchy, women will be empowered (I can’t remember her exact line of dialogue but it’s something to this effect). This is true on a basic level — truth-telling is certainly a powerful weapon in politics. But the sense I got from this scene was more along the lines of it’s enough to make your voice heard — a hollow individualist empowerment that’s more suited to voting campaigns and Instagram captions than it is to collectively fighting material problems like abortion bans and gender pay gaps.

I just want to pause here and share an image of Mexican women fighting the police during their successful campaign to get abortion legalized in the country, to show how women’s liberation really happens:

Okay. That said, within its limitations, Barbie’s feminism is effective enough. It articulates the frustrations and injustices of women’s oppression sharply and eloquently, and its fantasy vision of resistance is delightful. America Ferrera’s monologue about the futility of being a woman in this society is quite real and wrenching. This is exactly why the film is connecting with so many women; it’s not just about the dolls. I think it’s fine and even mildly encouraging that it does all this in the context of a blockbuster franchise movie.

The dismissals of Barbie’s feminism remind me of the leftist critiques of the women’s marches early in the Trump administration. These huge marches that gathered women (and a few men) from the broad left and center to protest Trump’s misogyny and Republican attacks on women’s rights were portrayed by some on the left as being compromised because they were largely made up of privileged middle-class pussy-hat-wearing white women who venerated Hillary Clinton despite her many problems, and didn’t have a perspective on class, race or imperialism. The best response to this came from Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor, the Black Marxist academic and author of From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, a book that changed my life.

Were liberals on the march? Yes! And thank God. The movement to resist Trump will have to be a mass movement, and mass movements aren’t homogeneous – they are, pretty much by definition, politically heterogeneous. And there is not a single radical or revolutionary on Earth who did not begin their political journey holding liberal ideas.

Liberals become radicals through their own frustrating experiences with the system, but also through becoming engaged with people who became radical before them. So when radicals who have already come to some important conclusions about the shortcomings of existing systems mock, deride or dismiss those who have not achieved the same level of consciousness, they are helping no one.

Meanwhile, the end of Barbie (spoiler alert) offers a different interpretation of the film’s politics. To me it says something that it had a big chance to nail down the girlboss narrative, and gave it away. In the last scene, we see Barbie starting her new life as a human, headed into an office building filled with anticipation. Everything about the way the scene is laid out leads us to believe it’s a job interview. I half-expected her to be hired as a Mattel executive, and I braced for disappointment. This is what a lesser film would have given us. As it turns out, her destination is, of all things, a gynecology appointment.

The way this scene completes the shift in the character’s style and color palette is pretty interesting too. She starts out the movie wearing various iconic and very feminine pink outfits (based on real Barbie outfits I’m told); in the middle of the film during her existential crisis she wears yellow (apparently a nod to the suffragette movement?); and in the closing scene at the gynecologist’s it’s a very plain beige jacket, jeans, and Birkenstocks (the latter coding Barbie as lesbian, probably deliberately). So Barbie doesn’t become a girlboss, but a very ordinary (working-class?) (probably lesbian?) woman, doing something all women do. It’s a nice touch.

There’s also some possible trans subtext here, given the previously vaginaless Barbie’s excitement about her new human body, as Them explains: “It’s a moment that may feel hilariously familiar to any trans woman who’s gone to the doctor for the first time after getting bottom surgery.”

7. “White feminism”— Gerwig has been tagged with the “white feminist” label for years now, at least since Lady Bird. I found it unfair at the time and still do. This is not the space for a detailed analysis of the uses and limitations of the “white feminist” narrative, but I will say I believe it’s best applied to women in the ruling class — Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, Australian mining boss Gina Rinehardt, to name a few. You know, women with actual power to devastate the environment or destabilize Libya — actions that disproportionately impact Black, brown and Indigenous populations — and who weaponize feminism to their advantage. It can be reductive when aimed at a filmmaker like Gerwig for making a semi-autobiographical movie about a working-class family in Sacramento, for the same reasons cited by Yamahtta-Taylor in her commentary on the women’s marches.

Barbie doesn’t offer any solutions to structural racism (I know that comes as a shock), but it makes honest efforts to be progressive. The cast is pleasingly multicultural — just the process of finding images for this article reinforced that for me. It was wholesome to see photo after photo of this beautifully multicultural cast inhabiting this vividly colorful, surreal world. Ferrera, Ariana Greenblatt, Issa Rae and Simu Liu among others have great roles and really shine here. The screenplay tackles intersectional feminism. Sasha (Greenblatt) snarkily dismisses Barbie as a white savior. The president of Barbie Land (Rae) is Black. The most important speech in the movie is made by a Latina (Ferrera). To go back to a point I made before, these things would have been far less likely or even unheard of in a blockbuster movie even ten or fifteen years ago. The changes we’ve seen are very much influenced by BLM and other social movements. It’s helpful to remember that the fight for racial justice waged in the streets has a real impact on mass entertainment, even if mass entertainment lags behind and is hardly ever truly radical.

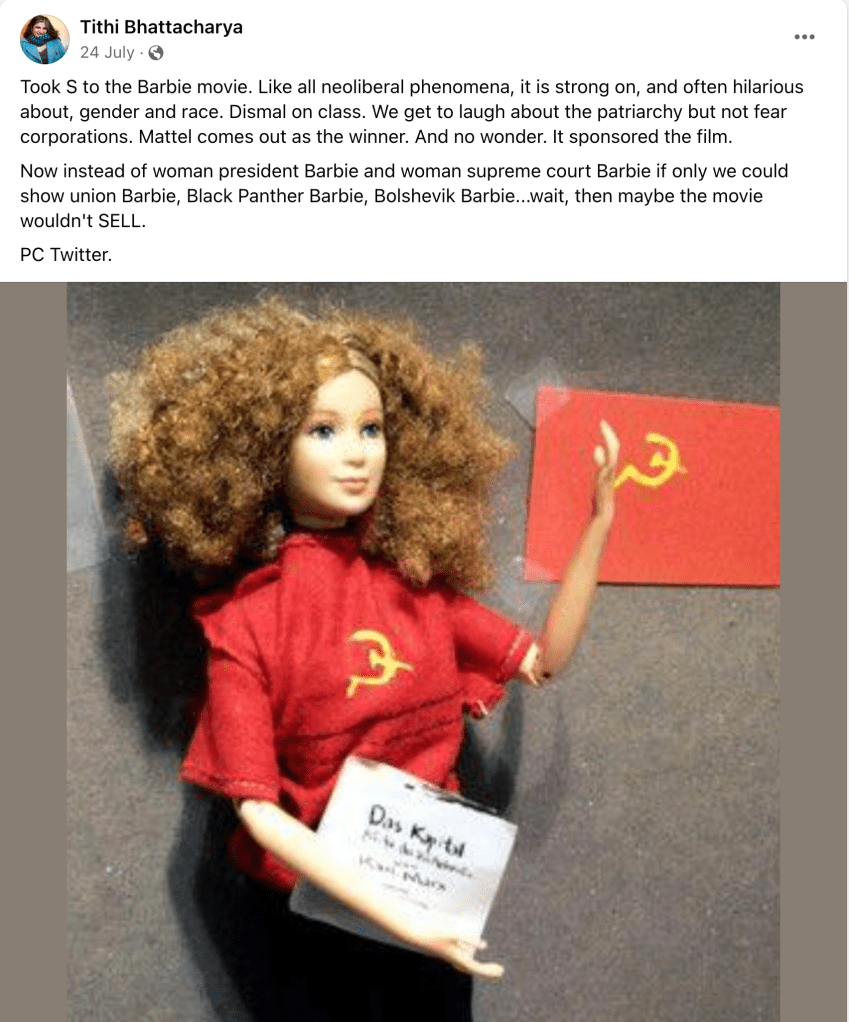

8. Class — In her excellent commentary on the film, Tithi Bhattacharya, the Marxist-feminist whose writings including Feminism for the 99% have been enormously influential on me, summarizes the problems with class in Barbie:

When the glass ceiling is broken, who cleans up the shards from the floor? Amid the perfectly proportioned Black President Barbies, and superbly manicured surgeon Barbies, one wonders who cleans the Dream House, who wipes down the counters, who struggles with minimum-wage jobs. And does the Black President Barbie order drone strikes on the Middle East?…

Mattel, unsurprisingly, asks women to be bosses, not to fight them. We get to laugh at the patriarchy but not fear corporations.

I agree with her that class is really lacking in Barbie, as it is in most entertainment under neoliberal capitalism — which promotes individualism as an all-encompassing ideology and leads us to believe that class struggle is a thing of the grimy, sepia-toned past.

What interests me is the subtle ways class imposes itself on the narrative despite the main thrust of the girlboss stuff. A comrade pointed out that Gerwig was raised in a working-class family (this was the subject of Lady Bird), and maybe that has something to do with it.

I’ve already mentioned the concluding scene, which suggests Barbie has joined the ranks of the working class. There’s also the importance of Gloria, Ferrera’s character. It says something that a working-class Latina (she’s an admin at Mattel) is the cypher for the film’s views on feminism. Though her monologue hits a lot of bourgeois feminist/girlboss talking points (“You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean”), its underlying message and despairing tone about how impossible everything is for women is distinctly working-class. It’s not nearly as impossible for bourgeois women as it is for working women, and working women will of course feel that when they hear the speech.

And the film does undercut the girlboss narrative, starting with the opening scene in which the idea that women can be judges or astronauts because of the inspiration of a doll manufactured by capitalists is openly mocked (the implicit point: we know most women can’t be those things).

9. LGBTQ+ — I’ve seen many perspectives on LGBTQ+ representation in Barbie, ranging from the criticism that it promised a lot but ended up being pretty hetero, to a comment I saw on my timeline: “From the high femme flamboyant queer side of the pond — me and the girls have already seen the film four times at this point. This is Mean Girls-level instant classic.”

I don’t have much of an argument to make either way and nobody is waiting for my input (nobody’s waiting for my input on any of this!). To me it’s just another example of how rich the discourse is around this film. I’ll just say two things: I was a little disappointed there weren’t more open LGBTQ+ characters in significant roles. As far as I could tell there are a few gay or lesbian Barbies and Kens hanging out in the background. Michael Cera’s Allan is coded as gay but if you weren’t aware of his history you might miss that. Doctor Barbie is played by a trans woman, Hari Nef (and what’s great about this is she’s presented as just another Barbie).

But on the other hand, the whole thing is so incredibly gay with all the colorful kitsch, fashions, musical numbers, the subtle and not-so-subtle coding of major characters, songs by Charlie XCX, Dua Lipa and the Indigo Girls, and on and on. Side note: The running gag with the “Closer to Fine” singalong in the car made me feel a euphoric mix of laughter on the verge of tears thinking about my sister and her daughter and how much they love the Indigo Girls.

I especially love that Ken’s warped conception of masculinity, which represents the patriarchy on the surface, is also, paradoxically, so very gay, with his leather and fur coats, and his obsession with cowboys and horses, and his sheer fabulousness.

The more I think about it, I’m convinced that that Mattel was squeamish about including openly gay characters — in the same way that Disney has dragged its feet on this for years — but Gerwig and her collaborators subverted this by making everything else about the movie as gay as possible.

10. Men — A few commentators have complained that a male character, Ken, is more interesting than Barbie. As I said I don’t really agree, but I venture to suggest that Ken’s importance to the story is because the problem of gender relations is central to women’s oppression, not because Gerwig is favoring a male perspective.

A more pertinent criticism I’ve seen is that in their climactic moment of redemption, Barbie seems to suggest it was her fault Ken felt so useless in the first place. I can’t remember the dialogue, and the way it resolves, with Barbie saying they don’t need to be anything to each other anymore, is satisfactory enough, but I do remember feeling uncomfortable about that in the moment.

My favorite thing about Ken’s story arc is when, after realizing the error of his ways in trying to institute patriarchy, he says he felt bad about it all along. “It was hard running stuff. I didn’t love it.” It’s a simple but poignant way to talk about how toxic masculinity hurts men too. As an autistic diagnosed in adulthood, this stuff really resonated with me. I never felt good trying to be a typical domineering male, wouldn’t have known how to even if I’d tried. I felt bullied or shamed or excluded by other boys or men all my life.

I suddenly feel like I could write an entire article about Ken and undiagnosed autism: that uncomfortable feeling of never having grown up; that inability to fit in anywhere or to figure out where you belong; that constant sense that there’s something you haven’t been told, some information you’re missing, and you’re not sure what it is.

11. Childhood — What I especially like about Bhattacharya’s article is that, although she makes these damning points about the “Oprah’s book club analysis of patriarchy,” she is generous enough to write about all the good reasons why so many women are embracing the film. She’s especially insightful on how Barbie represents something new in the cinema landscape, a fantasy world for women to dive into and relive their childhood, comparable to how Star Wars works for so many men. It gives women “a rare permission — to be frivolous and childish.”

Though it’s not for young children, Barbie really gets childhood, and that’s one of my favorite things about it. There’s a real understanding of the inner lives of little girls and how they play with dolls, represented most clearly and poignantly by the opening scenes in which Barbie plays in her dream house, floats down to her car (because that’s how a kid would move her!), goes to the beach, and throws a party. The Barbies and Kens are essentially children — they have a child’s understanding of conflict, sex, and everything. It’s both eerie and touching.

The plot points involving Gloria’s sadness and regret over her lost childhood (which manifests as Barbie’s existential crisis), and her alienation from her daughter Sasha, tie into all this, and really hit me hard as a parent. In many ways, aside from the feminism, it’s a story about the passing of childhood and growing up, represented by Barbie’s transformation from a childish doll into a grownup human.

This isn’t really a political point… or is it? Childhood is political too, right? Maybe that’s why we’re having this huge, fascinating, multifaceted debate over this movie about dolls in the first place.

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!

Feature image via Warner Bros.

4 thoughts on “Notes on the politics of Barbie”