I write about film all the time, but not all of it gets published here. When I see a film or a series, whether old or new, and decide I have something to say about it, there are, broadly speaking, two things that might happen. The first possibility is that I’m so obsessed with this film, or I have so many thoughts about its politics, that it needs to be unpacked in an essay. Those are the ones that end up here. In 2023, those objects of fascination included Andor, Barbie, The Return of the King (for its 20th anniversary), and the retrospective program of Bollywood classics starring Amitabh Bachchan that screened at Sydney Film Festival.

Many more end up as short reviews I post on Instagram and Facebook. In these cases I have thoughts on a given film, but not enough to justify opening up a draft, spending days writing and editing, finding images, captioning, tagging, and everything else involved with publishing here. It doesn’t mean I didn’t love the film as much as the ones I deem worthy of long-form writing. It just means I didn’t have a big argument to make — I didn’t have lots of thoughts to gather and organize. Or maybe I’m in the middle of something else and I can’t justify adding it to my long list of things to cover here.

Some people might find this a strange way to blog. Many blogs feature short sharp articles that are posted far more often than mine. For whatever reason, that’s just not how I do it.

But I recently decided I wanted to compile and archive my short reviews annually, because, despite being posted in a throwaway format on social media, I don’t consider it throwaway work. I’m proud of those little reviews and I work hard on them.

There are 12 films reviewed here. Most of the reviews are lightly edited, and a few are expanded from my original posts. They cover quite a range of styles and genres, from fantasy to neo-noir to a classic of experimental and feminist cinema, but you’ll notice quite a few of them are family films. Parenting life involves watching lots of movies with my kid, and I don’t just turn off my critical brain when I watch them; many of them inspire me to write as much as “films for grownups” do.

Emily the Criminal

A contemporary noir thriller produced by and starring Aubrey Plaza, Emily the Criminal follows a young L.A. worker who turns to petty crime and a life of hustling to pay off her student loans.

This is a smart, crafty film with a lot going for it. Its slow-burning tension is quite gripping; my partner and I meant to watch half of it and save the rest for the next day, but we couldn’t turn it off.

The fact that it foregrounds the social context of permanent crisis and economic inequality makes it extra compelling, of course. Picture Nightcrawler if it was directed by Ken Loach, perhaps. There’s a lot of good stuff about labor and exploitation; some scenes play almost like anti-work memes. I’m pretty sure that was a deliberate choice, and a canny one in this political climate. In fact there’s one scene in particular — the tense, brilliantly written and acted scene in which Emily grows increasingly combative while blowing an internship interview with an arrogant fashion publisher — that’s already iconic and has gone viral on leftist meme pages.

Overall the screenplay really has a visceral feel for what it’s like to fall through the cracks of society, and to get so desperate you make some bad choices. This is something I can relate to deeply from my destitute years in New York in the 90s, though I never quite ended up on the criminal side of the hustle game like Emily does. It’s especially worth noting that Emily struggles to find work because she has a felony on her record (if you don’t know how impossible life is for felons in the U.S., I encourage you to read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander). It’s also a meditation on the justified violence of women.

It’s a good film, not a great film. On the one hand it’s refreshing that Plaza and writer/director John Patton Ford do away with a lot of noir tropes. There’s not one gun in the film, which is just really cool and impressive, both for the way it challenges action-movie convention; and also for the way it builds sometimes dizzying suspense, as Emily gets into dire situations that other movie protagonists would shoot their way out of, and scrapes by on her wits and her courage alone.

But then, disappointingly, they give in to other tropes — especially the romance, which just made me impatient — and they don’t really sell all the plot twists.

It left me with mixed feelings: it felt a bit empty when I thought about it later; but then I found myself thinking about it a lot the rest of the year, so something must have clicked for me. It’s a unique film.

Plaza’s powerhouse performance is pretty much worth the price of rental. I’ve always been a fan, but lately I’m starting to realize she’s actually one of the best actors out there; her simmering resentment and desperation are palpable, and she communicates so much with a glance or a half-finished sentence. That she hardly ever smiles and always seems to be in motion, never able to relax, is the physical embodiment of the film’s themes.

Note: Emily the Criminal is the second really interesting, really original indie thriller that Plaza produced and starred in within a period of two years, also including the quasi-Lynchian Black Bear. In an interview after Emily was released, Plaza claimed that she, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg are the only ones keeping theatrical feature films alive. She was roasted for this, but dammit, she has a point (and let’s face it: the backlash was sexist, because if Ari Aster had said this, everyone would have thought it was cool, right?). I really appreciate that Emily is a feature film and not some half-baked Netflix series that goes on for way too long and gets even more heavy-handed with the tropes just for the clicks. More of this please! More brave and quirky films, less series!

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles

At the end of 2022, the late Belgian auteur Chantal Akerman’s 1975 magnum opus was voted as the greatest film of all time in the Sight & Sound critics’ poll. It was the first time a film directed by a woman had topped the once-a-decade poll (after decades of women filmmakers barely appearing on it). This result copped a fair bit of backlash that was often frankly sexist. You could say it was the arthouse-cinema version of toxic Star Wars fanbabies, as Akerman pinched the top spot from the iconic male directors who’d prevailed for so long, including Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. I’m tempted to talk about how absurd and idiotic this discourse is, but honestly I don’t think these jackasses are worth addressing.

Anyway, I felt embarrassed I hadn’t seen Jeanne Dielman before, so I was grateful that it screened at Golden Age Cinema here in Sydney, in a program celebrating the poll, so I could take it in on the big screen.

The irony of not having seen it before is that it’s exactly my kind of film. The most experimental film to ever place so high in the poll, it’s considered a milestone of slow cinema. It’s nearly three hours and twenty minutes of mostly static shots of a working-class Belgian woman (Delphine Seyrig) silently doing chores in her apartment over the course of three days. She’s a widow and looks after her son (Jan Decorte), a boorish uni student who takes his mother’s domestic labor completely for granted and never lifts a finger to help. Complicating matters, Jeanne is also a freelance sex worker who has men over in the afternoons to help make ends meet.

But the men in her life merely come and go; most of the film is Jeanne alone with her housework.

I realize watching this film may sound like hard work to some. Though I admit it takes a fair bit of patience, I’ve always loved slower, quieter cinema, even when I was a kid (I saw Picnic at Hanging Rock when I was 9 and it fascinated me). Perhaps it works on the same part of my brain as ambient music, which is an important part of my daily listening. And diving into Jeanne Dielman was such a welcome relief compared to the boring predictability and rigid story structures of the prestige TV shows that are all we’re allowed to talk about anymore it seems.

What’s hard to explain in a brief review is how hypnotic a film it is, and how the editing rhythm is actually quite thrilling despite all the long takes. There’s a running motif of Jeanne turning lights off and on as she moves from room to room in these rhythmic cuts that are strangely soothing to watch. During the entire three-hours-plus I was never even slightly bored, and I found it quite meditative. I had so many expansive thoughts about social reproduction, the oppression of women, and how different everything was in the midcentury period — the bland food, the fussy decor, the rigid gender relations.

It’s also a beautiful film, despite the constrained setting; the earth tones of the 70s apartment practically glow in the lamplight and indirect sunlight.

It’s such a moving experience too, despite how little “happens.” Because social reproduction is my work too, I was flooded with so much sympathy for this woman — and also really impressed by her discipline, how neat and orderly her apartment is and what a groove she’s in, the sheer physicality and ritualistic nature of her work.

Seyrig’s performance is magnificent (and not as naturalistic as it would seem, since she was not at all working-class or a housewife herself). It’s such a nuanced performance — Jeanne clearly enjoys her work a lot of the time, but you can also tell it weighs heavily on her too. She’s so fatigued and anxious and lonely. As the film winds on, taking its time, her chores repeating over and over, there are subtle signs she’s experiencing an internal crisis. Once I found tears coming to my eyes, for reasons I can’t fully explain, just watching her sit and have a cup of coffee while looking exhausted.

It’s such an immersive film, and the whole point of how long it takes with everything is so you can fully inhabit this woman’s life to the point that it feels like these things are happening to you.

There’s anger and protest here too: after decades of cinema in which women were mostly objectified when they appeared at all, Akerman is almost grabbing the viewer’s face and making you look at an ordinary woman’s daily life for over three hours.

I could go on about it, but I’m so glad the poll motivated me to see it; and it’s actually good I was late to the party because I know I got a lot more out of it now, cinematically and politically, than I would have as a callow youth in film school. Though it’s always pointless to debate the “greatest,” it was certainly one of the most powerful experiences at the cinema I’ve ever had, and its place at the top of the Sight & Sound poll is richly deserved.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Pardon me for a gushing review: this is an unreasonably great film (and now that I’m looking back, the year’s best film of any kind as far as I’m concerned). The first installment, 2019’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, was great too, but the sequel expands and improves on it by a lot. It’s a masterful action film, a masterful family film — a masterful film, period.

The wildly creative, jaw-droppingly fabulous animation alone puts it in a league by itself. Honestly my brain couldn’t process how they do all this; it’s a leap forward in animation that makes me feel old and unsophisticated.

There are so many styles and techniques, such a blizzard of clever visual references. Like when they show Spider-Punk’s universe, everything is rendered in punk cut-and-paste; there’s a completely different style for Spider-Man India’s world, with incredible texture and vivid color in this insane cyber-Mumbai/Manhattan megalopolis, and all this cultural detail — so many things happening in the corner of the screen you could never see it all. The dozens of styles switch rapidly, but also overlap in the same shot, collage-style, when characters from different universes interact. There’s hand-drawing and stop-motion Lego bricks and even live action.

But mentioning these more obvious visual motifs and gags doesn’t do justice to the depth and subtlety and beauty of it all, even in the backgrounds of dialogue scenes in the character’s homes, or in the wonderful cityscapes. There’s so much beauty in this film, it’s just gorgeous.

All that may sound like sensory overload, and it is at times; but for the most part the storyboarding and editing are deft, there’s a visual logic as it all unfolds, and it’s exhilarating and pure joy to watch. Directors Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson pulled off the seeming impossible in crafting all the visual chaos and nerdy Spider-lore into something so wondrous.

The visual element, as spectacular as it is, isn’t even the best thing about the film: what makes it truly great is how well-written it is (by Lord & Miller and Dave Callaham). It’s surprisingly moving, and there’s so much in here about parenting, about growing up, and of course about multiculturalism.

The allegory between having superpowers and being a closeted gay teen is a tried-and-true one in superhero comics and movies (think Brian Singer’s X2), but I’ve never seen it handled better than here.

I also felt it could be an allegory for neurodivergence. The fraught relationships that Miles Morales (voiced by Shameik Moore) and Gwen Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld) have with their parents and with their friends and with each other, their social awkwardness, and their emotional turmoil and pain, just resonate so much.

There’s a scene between Miles and his mom (Lauren Vélez) that made both me and my partner ugly cry in the cinema — this was not even a third of the way through the film. The screenplay is so rich and funny — like when something goes awry during an action scene, and Spider-Punk, a self-described anarchist, quips, “It’s a metaphor for capitalism.”

Most modern superhero films aim for this kind of thing in mixing melodrama and satire, but few succeed like this one, and none can compare to it visually.

There’s so much intelligence and heart — just the fact that you glimpse a “Protect Trans Kids” poster in Gwen’s bedroom; or when Miles’ mom snaps her finger at him and the sound is visualized by a little Puerto Rican flag graphic. Just the fact that a film can depict a Black and Puerto Rican rooftop barbecue in New York with such loving accuracy, in a way you rarely see in other media, and render it with such beauty, and depict an argument between a kid and his parents so honestly and sensitively (the acting is terrific), and really let the scene go on for a while and play out in a mature way, in and amongst all the adventure and genuinely thrilling action and the kaleidoscopic, psychedelic mashup of style and color, is… like I said, unreasonable to expect of any film, but here it is.

If not for the tedious middlebrow bias against animated films, and against superhero films, Across the Spider-Verse should rightfully be a contender for awards season; but it’s no surprise at all to me that it’s not taken seriously as a great film by the arbiters of such things.

Art College 1994

This year, as I often do, I worked for Sydney Film Festival as a freelance writer, meaning that I got to preview several films in the program at home and write them up. But due to life stuff I was only able to see one new title at the fest itself. Thankfully it turned out to be a winner. Directed by Liu Jian, this is a lovely film: an animated coming-of-age ensemble drama about art students in China in the 90s, clearly influenced by Richard Linklater’s wistful, talky dramas like Before Sunrise.

The young characters spend most of the film hanging out, drinking, smoking, bullshitting, flirting, and especially waxing philosophical about the meaning of life and the purpose of art in society. Through these long, slow, quiet scenes, undercurrents of romance or crisis wash in and out of the chatter and the meandering story.

There are interesting political themes, as the characters grapple with the clash between the rote Marxism they were taught in school and the reality of Chinese state capitalism as it reorients towards neoliberalism; and with Chinese nationalism and traditionalism juxtaposed with their fascination for the West. There’s some sharp discussion of gender roles and women’s oppression too.

The fact that the characters are arch-90s slackers who are obsessed with Nirvana and The Godfather films is so relatable for me. A bootleg cassette copy of In Utero is central to the story (it’s a shame they couldn’t license Nirvana’s music). The animation is gorgeous — picture a cross between a more low-budget Studio Ghibli flick, and the quirky realism of King of the Hill. It really maximizes the low budget in presenting each scene as a tableau without a lot of motion, but with a lot of color, beauty and expressiveness — like two characters laying in a park having a conversation, mostly still and placid with the occasional waft of cigarette smoke or breeze in the trees. There’s lots of nice texture and detail, such as insects crawling in the periphery, or the clutter of trash in a dorm room.

The fact that many of the conversations are about the value of traditional Chinese art versus Western art only makes the artistic quality of each frame more impactful. The story’s implosiveness and lack of resolution is overall a strength, and exactly my jam — though you could argue it’s maybe a little too implosive in the end. Still, a memorable film and highly recommended.

Elemental

I was shocked by how bad Elemental was; and really disappointed too, considering it was one of the flagship family films of the year — a big event for my family that turned out to be a letdown. It’s allegedly a Pixar production, but the quality is more like Stan Original. Pixar is responsible for many of the greatest family films of all time, and in recent years they’e remained very consistent (Coco, Soul, and Onward are all outstanding, while Turning Red and Luca are pretty solid). I don’t think it was unrealistic to expect more from this one.

Before this my least favorite Pixar movies were Cars and The Good Dinosaur. The director of the latter, Peter Sohn, is to blame for Elemental too; but both of those ones are like Miyazaki compared to this debacle.

The concept is so rife with problems: the four classical elements as beings who inhabit a city together, the tension and prejudice between them, and a fire person and a water person who “improbably” (read: predictably) fall in love. Like Zootropolis, it purports to teach kids about racism, but somehow reifies it instead.

What kind of message is it that fire and water can actually kill each other if they get too close? All the scenes showing this multicultural city just show how dangerous it is for everyone. Death is always imminent — the main character, Ember (voiced by Leah Lewis), is almost snuffed out several times just walking around or riding trains.

Nothing makes sense. The fire people (“Firish” people), who are recent immigrants to the city, are all confined to a clearly under-resourced ghetto — because they’re so dangerous to everyone else, right? And they shun and resent the other elements; they scowl at visitors and forbid interrelations. They are coded as Middle Eastern (or sometimes Jewish, or sometimes Eastern European), while everyone else seems to be… just “normal,” I guess? Instead of being a potent analogy for oppression, this is all just depressing and cliché-ridden.

The water people live in apartments that are like water parks, and they can disembody into water and travel through pipes, which reminds me of that meme about a gingerbread man in a gingerbread house: “Am I made of house, or is the house made of man?”

The thing is, fantasy stories for kids always have their gaps in internal logic; Toy Story doesn’t really make any sense either if you think about it too much, right? How have toys hidden their sentience from humans for so many centuries? What’s the nature of their consciousness? What does it actually take to kill a toy? But none of that matters because the Toy Story movies are so good.

I could easily forgive all the logical inconsistencies in Elemental if they bothered to sell it with a good story and good characters. But the story is so boring and dumb and that’s the real problem. It’s bafflingly uninspiring romance that’s only distinguished by the tediously predictable Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? stuff. Ember’s dad Bernie (Ronnie del Carmen) is just a set of tired tropes about grumpy, narrow-minded immigrant dads who pine for the old country. Ember’s love interest, Wade (Mamoudou Athie), is so dippy and unappealing he comes across as either a parody, or a covert villain.

The romance is so poorly written, and it’s hard to sit through their scenes together — but the efforts at suspense are even hackier. Water (regular water) from an overflowing dam is threatening the Firish ghetto — why don’t the water people just do some watery stuff and get rid of it? Because then this movie would be ten minutes long (like it should have been).

The only remotely engaging character is Ember. The fact that she’s angry all the time — because she’s fiery, get it? — is actually kind of cool and I like that as a lesson for kids (and adults for that matter): anger is good. But the fact that her people are racialized makes her constantly smoldering anger kind of unfortunate too.

The only other good thing is some nice background art and animation, especially in the city, but for the most part it’s cringe. Was this really made by the same studio that made Inside Out?

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

I watched this one because several friends said it was far better and more entertaining than they were expecting. This had the unfortunate effect of raising my expectations too high, so that it was somewhat disappointing for me. I recommend lowering your expectations back to where they should be: a middling-to-good D&D cash-in that also serves as a satire of D&D and the fantasy genre in general, with a funny screenplay, a great cast who often phone it in, and action sequences and effects that are pretty good but not game-changing.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s certainly better than average — tightly written, imaginative, and charming. The many insanely nerdy references to D&D lore tend to enrich the proceedings and not derail them. I played D&D for a couple years in the early 80s, and I have fond memories of it, but it never became a way of life for me. So I caught some references (owl bear, gelatinous cube) and missed others.

The main problem with the film is its frustrating way of poking you in the shoulder and letting you know it’s kidding just when it gets suspenseful and exciting. Chris Pine’s performance is so snarky it’s like he thinks this is an SNL skit, and after two hours that’s tiresome — especially compared to some of the others, like Justice Smith, who’s actually great here.

There’s one tragic scene in which the acting by Pine and Michelle Rodriguez is so indifferent it feels like a high-school Shakespeare production. Is this deliberate, part of the satire? But satire can be emotionally engaging too — see also The Princess Bride. Or, to pick a more recent and pertinent example, Pixar’s underrated Onward. That one is also a satire of D&D and fantasy flicks, but it’s ten times more substantial and affecting (it makes me ugly cry every time I watch it with my kid). This one really suffers by comparison.

Now that my gripes are out of the way: if this is at all your thing, you won’t be wasting your time. It’s definitely fun and never boring, there are some memorable setpieces, and the diverse cast is nice to see (diversity in fantasy is important). Hugh Grant looking like he’s having the time of his life as the villain is arguably worth the price of rental.

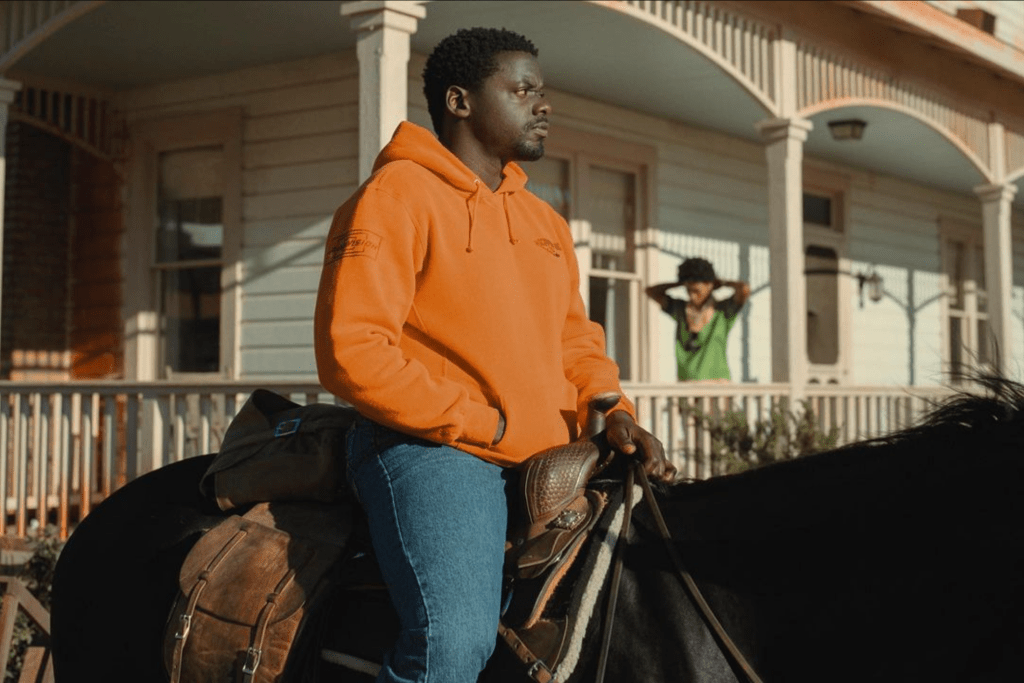

Nope

I wasn’t sure what to think after watching Jordan Peele’s third feature. I found it objectively great and fascinating, but I felt like all its elements didn’t quite gel. I was also a bit disappointed it didn’t have the impactful social commentary of Get Out (I haven’t seen his second film, Us, so I can’t compare it to that one). Of course, Peele might just want to make a weird off-kilter action-horror movie without an overt message, like Spike Lee sometimes just wants to make a detective thriller. And it does have plenty of poignant subtext, such as the erasure of Black cowboys from history, and the Black contribution to the development of cinema.

I love how Peele proves he’s a big ol’ nerd here. The plot is such a nerd plot — you know, there are certain rules about the alien nemesis carefully laid out (no spoilers but to name classic examples from other films: “never feed them after midnight” or “they have acid for blood”), and everything revolves around the heroes trying to navigate or grapple with those rules. Nope does that better than any recent film I can think of.

I also liked that the sibling protagonists (Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer) are kind of cantankerous people, and they bicker a lot. Instead of conventional action heroes they feel like real people caught up in a crazy situation, which amplifies the suspense.

This may sound weird but Nope reminded me a lot of M. Night Shyamalan. It’s quirky and nerdy and really takes its time unfolding, with a lot of misdirection, like a Shyamalan film. But the suspense and the buildup to the jaw-dropping finale top anything Shyamalan’s done this century. I also saw a big John Carpenter influence. On the downside, I hate to admit it but I’m not sure the visual effects live up to the suspense and horror.

But days later I was still thinking about it. There’s certainly no other film like it. Many classics start out as films that take a while to digest, and I have a strong feeling it’ll age well (certain scenes have already become iconic). It’s not like I would want it to be more conventional.

One thing Nope certainly has is visual power: it has so many astonishing, indelible images. Not only [redacted to avoid spoilers], but the chimpanzee! the falling coins! the skydancers! the praying mantis! It’s a beautifully made, at times befuddling, unforgettable film.

Field of Dreams

I wanted to go back and review a couple of the “dad movies” I watched with my actual dad on my recent trip to the US. The first one is an all-timer: Field of Dreams.

The first thing you should know is I’m a baseball fan; that means I love certain baseball movies automatically and unreservedly, and Field of Dreams is firmly entrenched in that hallowed baseball movie-canon.

Still, it’s good to watch with a critical eye. I hadn’t seen this film for a long time and it was really interesting to revisit. One thing that really jumped out is how wonderfully low-key it is. If it was made now, it would be adapted into a Netflix series and bloated with unnecessary subplots and CGI. It’s so refreshing how slight the narrative is, how little happens in terms of action, and how it’s mostly made up of conversations. That pacing is really what makes the emotion so impactful.

The performances are superb. Before he was a symbol of Hollywood hubris and a conservative icon, Kevin Coster was so good at conveying this sense of an ordinary person caught up in crazy events, kind of like a modern Jimmy Stewart. His reactions and line readings are so relatable they make you believe this is happening. Amy Madigan, one of my favorite character actors of the 80s (Streets of Fire forever!) is so brilliant and boisterous in what would have otherwise been a thankless role as the wife who believes her husband’s crazy dreams.

I love James Earl Jones so much in this movie. I love how irascible and funny he is — it’s such a great contrast to that Voice of God that he has. I especially love the interactions between Jones and Costner; some of their scenes together are so naturalistic and downright weird they feel improvised.

All this before we get to Burt Lancaster! and Ray freaking Liotta!

On the other hand, it’s disappointing when Ray tracks down Mann, the reclusive Black radical writer, and Mann talks bitterly about how he gave up on changing the world. That feels dishonest to me, and very much like a dated 80s trope — Hollywood attempting to exorcise the demons of the Vietnam era. Despite all the talk of radicalism, the fundamental worldview of the story is pretty conservative: baseball represents all that was once good about America, and if we could just see that in these crazy times, everything would be okay. It occurs to me that this wistful view of pastoral traditions plowed over by capitalist progress appeals to all sorts of people, left, right and center, in the same way it does in The Lord of the Rings.

Despite the conservatism, I still enjoyed the unusually rich backstory about the antiwar and Civil Rights movements of the 60s. In the current political climate there’s no way a baseball movie would portray leftists so positively. The stuff about the banning of books is of course more relevant than ever. I love how Madigan slams her right-wing PTA nemesis as a “fascist cow,” it’s such a genuine and raw moment.

Side note: it’s pretty interesting that in the novel the film is based on, Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, the reclusive writer in need of redemption is J.D. Salinger, and that they changed it in the film adaptation to be an entirely fictional Black writer. That feels more like something that would happen now (and it would face a backlash from toxic commentators complaining about the casting change as “wokeness out of control!”).

Mixed politics aside, I loved Field of Dreams as much as ever. Watching a movie about redemption between father and son with my dad, whom I hadn’t seen in seven years, I had to turn away to hide the tears.

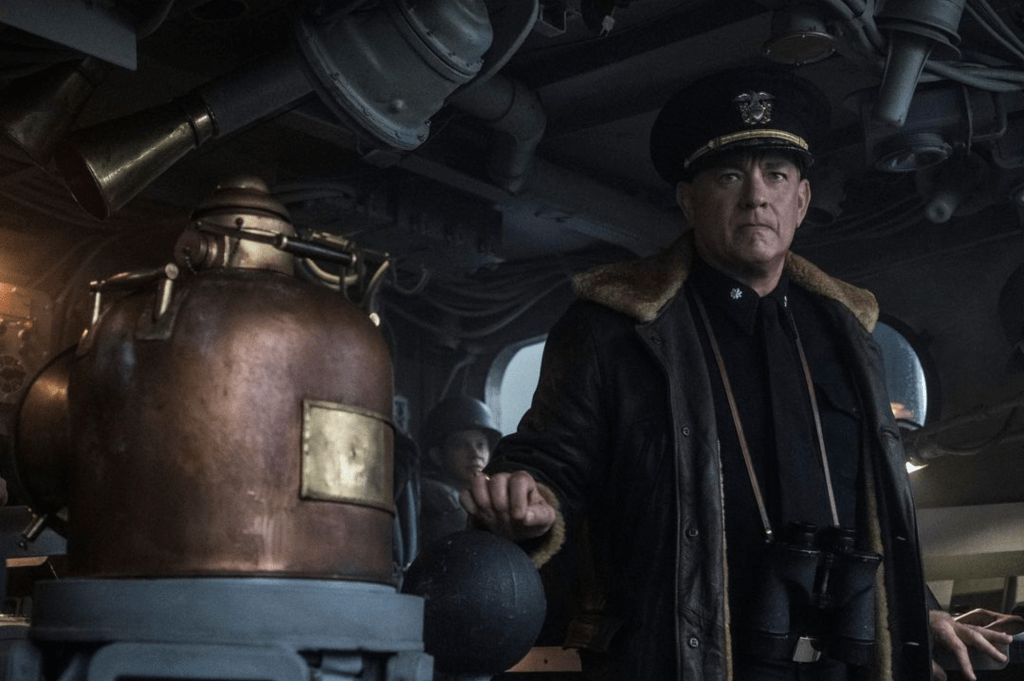

Greyhound

Dad Movie no. 2: When you see “Tom Hanks” and “World War II” in a movie’s blurb, you expect lots of sentiment about the “greatest generation” and a certain brand of centrist nationalism. I love nautical fiction and I would have been on board anyway, but I was so pleasantly surprised at how Greyhound left most of that out and turned out to be something much more compelling.

Based on a 1955 novel by C.S. Forester (of Horatio Hornblower fame), Greyhound is about a middle-aged US Navy officer in command of his first mission escorting a merchant convoy across the North Atlantic. The screenplay (impressively written by Hanks!) is focused on the crossing of the “Black Pit,” the zone in the middle of the ocean where ships are out of range of air support and most vulnerable to attack from German subs.

Once we’ve established that basic narrative and those few elements — a convoy, four battleships tasked with defending them, the unseen enemy, and the ocean itself — from there it’s simply an exercise in grinding, relentless tension, in some ways so minimalist it might as well be an arthouse film. Outside the horror genre I can’t remember a recent mainstream film so ruthlessly focused on atmosphere and suspense, and so unconcerned with convention or even with making the viewer comfortable. About an hour and a half in, my dad made a comment about how the constant tension was almost unpleasant (and he’s the one who’d seen it before and recommended we watch it!).

Most of the drama takes place on the cold, dark, noisy bridge of the command ship; it’s very dialogue-heavy and stagey (in a good way). The rapid-fire commands and nautical lingo aren’t explained at all; after the bare-bones exposition, the viewer is expected to plunge into the mood and read from context; it’s amazingly immersive.

I really admire how it avoids corny war-movie tropes. In a lesser film, the captain’s inexperience and uncertainty would mean protracted arguments about strategy and rebellious grumbling among the crew over a predictable three acts with a pat redemption at the end.

There’s very little of that here. There are no subplots, no backstories (except for a brief, fairly trite scene between Hanks and Elisabeth Shue as his fiance at the beginning, which seemed tacked on). We get a sense the crew is uneasy, but it’s all done with facial expressions and the briefest pauses in the dialogue (the acting is terrific). Hanks’ character stays on the bridge for days, without eating, drinking only coffee, to the point that he’s almost hallucinating with exhaustion. His suffering adds to the unsettling mood for the viewer.

Despite all that minimalism, Greyhound is visually brilliant. So many modern action films feature muddled, confusing action sequences, but here the viewer always knows where they are in the fleet, what’s happening and what’s at stake, and that’s down to great direction (by Aaron Schneider) and great editing (by Sidney Wolinsky). The effects are especially impressive: I don’t think CGI could have depicted a naval battle so seamlessly and with so much depth, to the point you feel a bit seasick watching it, even ten years ago. Once it kicks in, the action is really exciting, in a way comparable to Star Trek at its best.

Kudos to Hanks and his collaborators for getting so raw and stripped-down with this one. I don’t know if I would call it a great film, but it’s a very gripping and effective one, and if you’re into war or nautical movies it’s a winner.

Political notes:

- There are no women in Greyhound, except for the five-minute scene with Shue, and like I said that felt tacked on by the studio. Almost all of it is set on a WWII naval vessel during a time when women were excluded from serving in combat, and the story makes no bones about that. It depicts an era of rigid gender disparity in an honest way; but I wouldn’t blame anyone if they wouldn’t be interested in watching for that reason — it definitely fails the Bechdel test and probably every other test.

- One of the most interesting undercurrents in the film is the relationship between Hanks’ character and his Black steward (played by Rob Morgan). [spoilers follow]

It becomes clear the captain and the steward have a lot of affection for each other (like I said, nothing is spelled out and you have to read it all from context clues). During the mission the steward keeps trying to get the captain to eat to no avail, in an almost motherly way. Halfway through the film, the steward is tragically killed in battle. Later, in a stressful, confused moment, the captain mistakes another Black crewmember for the dead steward, and then immediately regrets it.

I think they were trying to depict WWII-era casual racism and the class disparity between officers and crew bluntly — rather than dishonestly trying to make out like the captain is some kind of progressive. Yet because racism and segregation aren’t overtly addressed elsewhere in the film, and because it’s such a typically conservative genre, it might come across to some viewers as being rather clumsy and insensitive. It’s an uncomfortable moment for sure — but I think it’s meant to be. - I mentioned that the nationalism is downplayed. Of course the context is nationalist (and if you’re not into that then this is not the movie for you), but I was just impressed that the screenplay made very little reference to patriotism or God and country, or how we’re doing all this for a higher cause, compared to Saving Private Ryan (a film I love but which is politically problematic). There’s very little sentiment at all; it’s mostly just about survival; and the stripped-down story could be transferred to any war, any nation, any navy, and it would be exactly the same.

Bait

Mark Jenkin’s microbudget drama centers on class conflict in Cornwall, with a strikingly raw, lofi style directly tied to its themes. Shot on 16mm in grainy black-and-white, hand-processed, with the sound added later, it’s a film that foregrounds its craft, minimalism, and opposition to convention — the cinematic equivalent of a Fugazi album.

Edward Rowe plays Martin, a down-on-his-luck fisherman whose brother (Giles King) sold their boat and the house they grew up in to cash in on an influx of rich, gentrifying Londoners. Scraping a living from fishing with nets on the beach, Martin seethes with scorn for the family occupying the ancestral home, with their posh accents, foodie-ism, and tacky remodelling. Meanwhile his nephew (Isaac Woodvine) has a fling with the family’s daughter.

Short take: a beautiful film (sometimes astonishingly beautiful, especially the scenes shot at the beach) with a suspenseful and touching story. It’s a refreshing departure from the usual middlebrow arthouse fare, and for me a nice callback to the late-80/early-90s indie vanguard of Lee, Jarmusch and Linklater.

Longer take: The class conflict is painted with such broad strokes it borders on clichéd. The posh characters are a bit too comical, and the dialogue is stiff at times. Maybe all of that’s intended (like how Jarmusch’s dialogue is always stiff on purpose), but since it’s hard to tell what was intended, it feels a little awkward.

The fact that Martin is an aggrieved small businessman lends a conservative edge to his character, which is realistic but doesn’t always make him very sympathetic (the bougies are far less sympathetic, of course). The only genuinely working-class character is the young bar worker brilliantly played by Chloe Endean; I found myself wishing the film was about her.

Some of the glitch and distortion in the film stock was clearly added on purpose — that plus the unsynched soundtrack makes it seem like an experimental film. But at times the distortion just seems showy, like when an electronic producer adds pop and hiss to a clean track, and it has the effect of taking you out of the story. The rapid-fire jump-cut montages meant to build Hitchcockian tension sometimes just feel student-y.

Bait is a very compelling film, but overall it didn’t hit me as hard as I’d hoped.

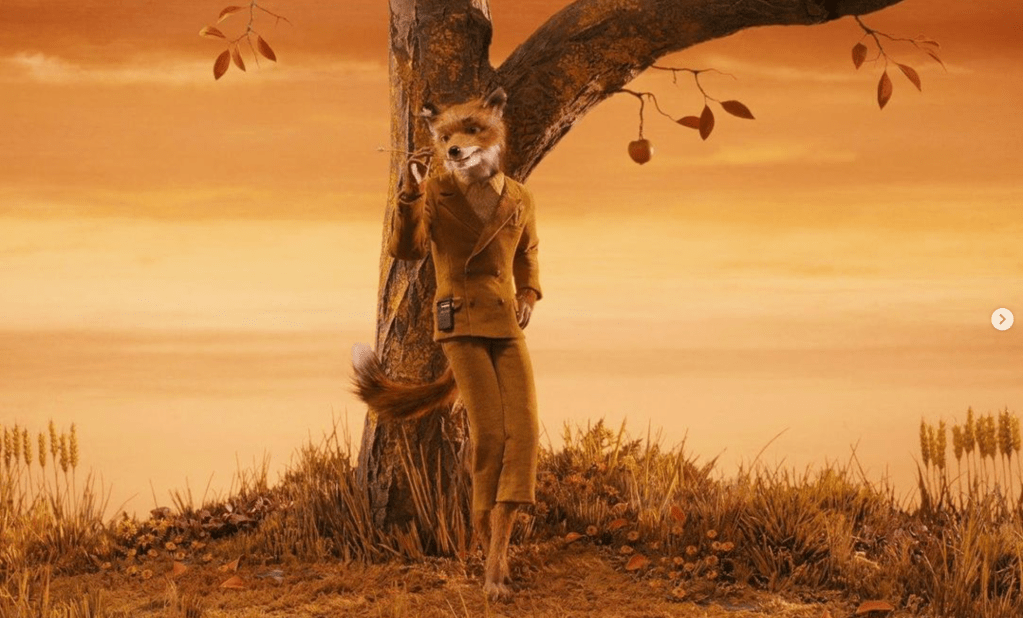

Fantastic Mr. Fox

One of my favorite cinema experiences of the year was rewatching Fantastic Mr. Fox with my son. It was his first time; he chose it because his class read the book in school.

My feelings about Wes Anderson are complex. I cherish him as much as the next white hipster, I get defensive when he’s dismissed, and Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums are two of my favorite films. But his preciousness and overwrought style get a little tired the longer his career goes on, and I just haven’t been interested in his last few efforts.

I rewatched this a couple of years ago by myself, and while of course I found it brilliant — no doubt one of the best animated films ever made — it left me a bit cold. Anderson has this thing for difficult, selfish male protagonists, and I’m really moving away from that. I’ve also recently decided I’m not into Roald Dahl; across a lot of media, I just find his stories unnecessarily mean and unpleasant and dare I say overrated.

But rewatching it again with my son was revelatory. It’s maybe the most “adult” film he’s ever seen, and his fascination with the violence and the characters’ cynicism and bickering gave me a renewed appreciation for what a wonderful screenplay it is (by Anderson and Noah Baumbach). Same with the great voice performances by George Clooney, Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, and especially Meryl Streep, who is so brilliant and really elevates the unenviable role of the long-suffering woman who puts up with the difficult Andersonian man (“I’m going to lose my temper now”).

Again, my son isn’t used to this kind of wryness and sarcasm and conflict in movies and I think he was delighted and stimulated by it. At one point Mr. Fox says something awful to his son and my kid asked, “Is that mean?” and I was like, “Yeah he’s being really mean to his son.” This was depressing when I was watching alone, but watching with him it felt like a lesson.

More than anything he especially loved the texture, detail and precision of the animation and world-building — the infrastructure in the background, including powerlines (which he’s obsessed with), the diorama-like sets, the intertitles, and all the cleverness in the corner of every frame. In other words he loved it for its Wes Andersonness, and it was so fun and wholesome to share with him.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem

This latest reboot of a tired franchise lands on the tier of unnecessary excellence — the kind of kids’ film that, while being nowhere near the level of, say, Miyazaki, or Pixar at its best, is still way more clever, imaginative and funny than it needs to be in order to make the same amount of money. If you’re not a parent I can’t explain what a pleasure and a relief that is.

This was produced by Seth Rogen and directed by Jeff Rowe, who also did the unnecessarily excellent The Mitchells vs. the Machines. It has that seemingly hand-painted, textured animation style that’s becoming trendy in family fare: Mitchells, The Bad Guys, and of course the Spider-Verse movies. In this case the style is deliberately choppier, so it looks a bit like a kid’s sketchbook; I love that.

Mutant Mayhem is clearly indebted to Spider-Verse not only in its look but in its anarchic teen spirit. It can’t compare to Spider-Verse in emotional impact and boundary-pushing; it’s not great cinema, merely worthwhile. But it’s nice that the bar has been raised so high.

I’m slightly too old to have ever been into TMNT, but I know enough to know that what works so well here is that instead of portraying the Turtles as boringly typical bros, they are kids who are plausibly goofy, anxious, and naive (credit to the four young voice actors: Micah Abbey, Shamon Brown Jr., Nicolas Cantu, and Brady Noon). They talk over each other, and make dumb jokes that don’t feel like cynical screenwriting but like the jokes kids would really make. The screenplay is sharp, and there are lots of meta gags and nods to progressive politics.

It’s surprisingly gorgeous at times — such as the shots of the New York streets at night with city lights illuminating the characters. There are some cool multimedia bits, like when the Turtles sneak into an outdoor screening of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and the actual movie plays on the animated screen. The music is great: Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross did the score, and they licensed some absolute classics including “Cavern” by Liquid Liquid and “Eye Know” by De La Soul. I honestly couldn’t believe how good the music was.

All family movies have to have stunt casting for marketing these days, but Jackie Chan as Splinter really works. Ice Cube as a mutant Blaxploitation gangster villain named Superfly is worth the price of admission, he’s so good and perfect in the role.

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!