Star Wars will never be better: A look at the cinematic and political power of Tony Gilroy’s masterpiece

So here I am with my third piece about Andor, and a fourth on the way. Having already written two long essays about season 1 (the first piece a broader review of the show and its excellent politics, the second one focusing on its resonance with Palestinian resistance), going into season 2, I didn’t assume I would have more to say. In fact I hoped I wouldn’t. I’m always feeling behind on this blog, and the less compulsive I am about the topics I cover, the more I can catch up with my backlog of ideas.

Of course it doesn’t really work that way. I don’t feel like I actually get the final say in what I write about; it’s as though it’s dictated to me by the universe. If I watch something and it leaves me pacing around the house feverishly, talking about it with autistic obsessiveness to anyone who will listen, or writing long Facebook posts that leave me feeling I have much more to say, eventually I have to give in and open up a WordPress draft. Andor season 2 did all that to me by the end of the first three-episode arc. If anything I was more obsessed than I was with season 1.

This series got into my head so much it felt like a part of me. I vividly remember one chilly, grey autumn afternoon here in Sydney, around the time I was in the middle of season 2, walking around the city after my classes, looking up at the steel and concrete structures looming over me in the fog, and listening to dark ambient music (GAS’s Narkopop LP to be exact). Feeling like I was living inside Andor’s brutalist sci-fi dystopia, and pondering how closely it resembles our own.

Movies do this to me from time to time. My reference case for this mood is Blade Runner. I’ll never forget seeing the director’s cut as a film student in 1991: walking out of the theater in Hollywood late at night with the strange sensation I was stepping into a future cyberpunk Los Angeles. Like the movie had become real, or I’d been absorbed into it — possibly due to a combination of autistic sensory overload and my childlike imagination. It’s both exhilarating and spooky — when a movie’s cinematography and design, its storytelling, its social relevance, and its overall aesthetic is so powerful that it invades your consciousness like that. It’s a natural part of being a cinephile, I imagine; but for me it undercuts it too, because when a movie leaves me this spellbound, I don’t want to see another one for days, so the spell remains unbroken.

And I can safely say a TV series has never done this to me before. So why does Andor captivate me so much — and thus compel me to write about it so much?

I think it exerts such a powerful pull on a few different levels. First of all I’m a big dork: I’ve been a fan of Star Wars since the first installment was released when I was six. A common refrain we’ve been hearing from both critics and fans is that Andor is Star Wars at its very best. Now that season 2 over, I think I have to agree. It’s like they made a designer drug for someone of exactly my age and tastes: everything great about Star Wars, few of its silly excesses, in a shortform series marked by outstanding writing, acting, and filmmaking… and make it dystopian… and make it political.

Importantly, Andor’s appeal extends beyond the Star Wars fanbase. It’s the first Star Wars content made strictly for an adult audience, and lots more people besides the hopeless geeks who argue over lightsaber colors tuned in to check it out. It’s grabbed so many people because of its its mature twist on a beloved franchise, its high production quality, and its slow-burn drama; but I think it’s obvious that its success also has a lot to do with its politics.

Think about the way season 2 landed three months into the nightmare killer-clown show that is the second Trump administration. This was perfect timing for it to become an outlet for all our collective angst — commenting on our deteriorating political landscape and our burning world with eerie perceptiveness and grim realism, in the same way Children of Men did, while also showing us a way forward with its rousing depiction of people’s rebellion against fascism. There was something cathartic about watching it this year; it felt more important than just a TV series.

Just look at all the memes. If the sheer number of politically themed Andor memes were any measure, many viewers took the show seriously and applied it to real life — to Trump, to Gaza, and to the anti-ICE rebellion in Los Angeles. This as much as anything convinced me that Andor was worth discussing in more depth.

If anything, season 2 was more politically impactful for more people, since the ratings were much higher than the first season’s. In the week the three-episode finale arc dropped in early June Andor actually topped Nielsen’s streaming chart. That’s pretty cool for a Star Wars series, especially one without lightsabers or Baby Yoda, and whose politics are unmistakably leftist.

And let me just say it’s delightful and refreshing to be comparing a Star Wars series to Children of Men and Blade Runner in all sincerity, and talking about its political relevance. It’s the first time Star Wars has been cool since I was a kid.

All this is to say that Andor season 2 is one of the best things I’ve ever seen, and more than that, it mattered to me. It gave me something to dive into and look forward to every week during a very difficult time, for the world and for me personally too (long story but I lost my mom in March).

Yet it disappointed me too! And that’s another reason I felt the need to write about this season. I don’t mind admitting that a series could move me so much and let me down at the same time. In particular, I found the last half of the final episode very frustrating and unsatisfying after the dizzying heights achieved in the 11.5 episodes before that (23.5 if you count the mostly unalloyed brilliance of season 1). I’ll get more into it later, but in short, I hate that showrunner Tony Gilroy felt the need to lead into Rogue One so heavy-handedly. So many prequels do this lately, and it’s a problem. I think Andor is far superior to the overrated Rogue One and ought to stand on its own as a narrative.

In the end the prequelitis wasn’t a complete disaster. The last episode pissed me off when I first watched it, but as more time passes, it’s the good bits that occupy my mind more and define the season for me, and it’s easier to forget how weak the conclusion is. But I still want to discuss it because Andor is one of the best series of its kind or any kind, and it deserves a better ending.

This commentary is divided into three parts over two articles. I’ve labeled the three parts “arcs,” like the story arcs in the series. Arcs 1 and 2 are contained here in this article. The first arc gets into the good stuff — all the things that made this season so uniquely great and compelling on a cinematic level. Arc 2 is about the politics — tackling how season 2 built on the first season’s wonderfully believable and nuanced view of social revolution in a galaxy far, far away. Arc 3 is where I’ll air my complaints about the ending and the problem of prequelitis. It will be published separately in a few days (I’ll link it here when I do).

There is so much going on in Andor, so much to say about it (to paraphrase Karis Nemik). Any new piece of Star Wars content unleashes an entire industry of discourse (some of it toxic, of course). With Andor the discourse has been supercharged and has spilled out of gates of the fandom because of its political depth. Every day I see more cool shit — like this review at Left Voice arguing that Andor makes use of Brechtian theatre techniques to provoke radical conclusions in the viewer; or this interview with Gilroy in which he cites Leon Trotsky as an influence on the series; or the amazing propaganda posters in the Rebelión zine that Disney published to wow Emmy voters. Finding a throughline in my own commentary and not getting overwhelmed by the nearly infinite discourse was a challenge, and often meant putting blinders on and ignoring it all so I could clear my head and write. Otherwise I’d never finish.

Arc 1: The good

Warning: There are lots of plot spoilers below for Andor season 2.

Many of the points I made in my first essay about the brilliance of season 1 also apply to season 2. Gilroy and his collaborators did a great job of making the new season flow on from the first one, while maintaining the stellar quality (that is, until the prequelish shenanigans at the end). So I won’t rehash it all; instead I’ll focus on a few key things that make it stand out, and at times top season 1.

Andor season 2 is probably the most suspenseful and exciting TV I’ve ever experienced. Working within a four-arc narrative structure that’s more clearly defined than the first season’s gripping series of climactic arcs, Gilroy and company build suspense that’s at times almost unbearable. I was literally doing the cliché and sitting on the edge of my seat during some of the powerhouse setpieces — the Imperial raid on Mina-Rau, the Ghorman massacare, Mon Mothma’s escape from the Senate chambers, Kleya Marki’s infiltration of the hospital, and Cassian Andor’s extraction of Kleya from Coruscant, to name a few unforgettable highlights among many.

Importantly, this excitement has more to do with how much we care about the characters and their lives, goals, and ideals than it does with the action itself.

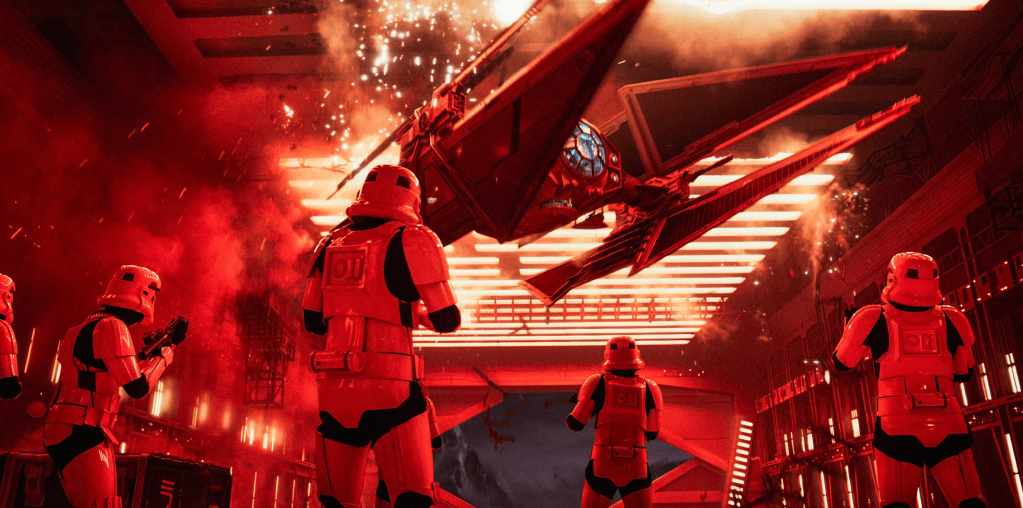

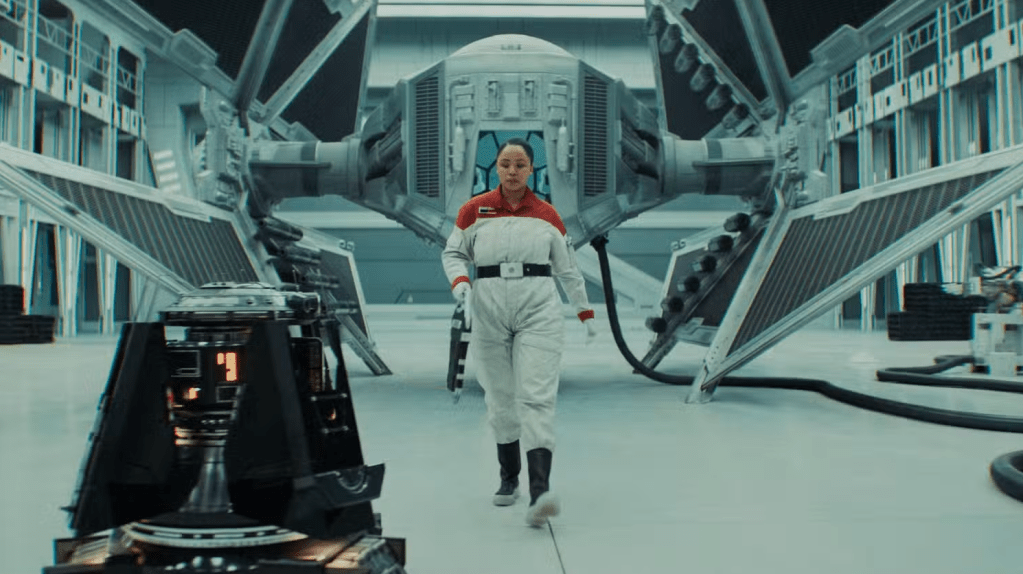

To be fair the action is at times blistering — I love the first sequence, in which Cassian (Diego Luna has never been better) steals a TIE avenger from an Imperial base. It’s a rousing tribute to space battles throughout Star Wars history — a more direct tribute than anything in season 1 — as Andor evades his pursuers in a canyon that feels a great deal like a Death Star trench.

Yet many of the key moments are more about setup than payoff. The clandestine raid on an Imperial arms shipment on Ghorman feels like it’s going to turn into a huge battle, but it climaxes with a single blaster shot. All the suspense we’ve felt as the action built up is then transmuted into tragedy, as we contemplate the human cost of armed resistance. This emotional depth is far more important than any shoot ’em up. It’s an audacious twist by the writers, one of many.

This is what people mean when they say Andor is slow-burning; but as I’ve said before, it may seem “slow” to some because there aren’t lightsabers flashing every 10 minutes, but that doesn’t make it less thrilling. The deliberate pacing makes the big moments more explosive.

The writing is so good throughout; from the very first scene you sense you’re in the hands of expert storytellers, and the way they take you for a ride and keep you guessing is such a pleasure. The writing works so well because of its economy and minimalism, and its trust in the audience’s intelligence. Season 2 tells the story of the four years before the events of Rogue One and Star Wars; but it does so episodically, with each of the four three-episode arcs giving us brief snapshots of the nascent Rebellion separated by a year. Each arc is designed to play somewhat like a feature film.

This unusual structure was in its inception a compromise, born out of “desperation” according to Gilroy. The original plan was to have a five-season series with each season covering one year before Star Wars. But the production delays caused by the COVID pandemic meant Gilroy had to follow up season 1 by squeezing the final four seasons’ worth of story into the four arcs of season 2.

Though some fans are disappointed by this truncated narrative, I think the results are brilliant. They manage to pack four seasons’ worth of suspense and excitement into this season, and I think that’s down to the minimalism. It’s easy to picture the full five seasons being excessive, as all TV series become excessive the more they drag on. There’s no excess here.

A lot happens offscreen, and this indirectness or obliqueness, this working with empty space as it were, becomes an important storytelling device. One of the main plot points is the Empire’s secret plan to gouge-mine the planet Ghorman for a mineral needed in the construction of the Death Star. This means the effective destruction of the planet and genocide for its inhabitants. The Ghorman resistance and the Rebels scramble to expose the plan to the rest of the galaxy as the mining equipment is covertly moved into place. Yet we never see this fearsome planet-killing mining equipment that’s so crucial to the story; it’s only talked about. It’s much more interesting that we don’t see it.

Similarly, we don’t see Cinta Kaz’s assassination of Mon Mothma’s blackmailing old friend Tay Kolma (Ben Miles), another pivotal moment in the season; we only see Cinta (Varada Sethu) whisk him away posed as his driver. The unseen act of bloodshed makes Luthen Rael’s ordering of it over the wishes of Mon (Genevieve O’Reilly) seem that much colder. A lesser series would have gotten bogged down showing us how it happened, when the drama is actually located in Mon’s complicated feelings of relief and horror — which she copes with by getting wasted and dancing to galactic house music, a great note of camp amid the drama.

We never find out what happens to Cassian’s fellow spy (beautifully played by Rachelle Diedericks) after she enables his escape from the Imperial base at the start of the first episode; we never even find out her name, yet the camaraderie and emotional connection they share in passing establishes the whole tone of the season.

That ability to create a believably lived-in character, give us insight into her motivations and her inner life, make us care about her within a few lines of dialogue, and then leave us guessing at her fate, is something that happens again and again over the course of the season. It generates so much depth of feeling for this fictional revolution; and in many ways it embodies the politics of the series, because Andor is all about the collective.

This works on a tragic level too. There’s some indication that Mon’s driver (Lee Ross), an Imperial spy, has decided at the last minute to turn and join the Rebellion on the day she gives her antifascist speech to the galaxy and flees the Senate. But Cassian kills the driver before he can make his change of heart known.

Or did we just imagine he wanted to be a good guy? It’s pretty subtle, mostly down to body language, and you might miss it, but that little bit of ambiguity makes Cassian’s brutal (but very rational) dispatching of him hit that much harder.

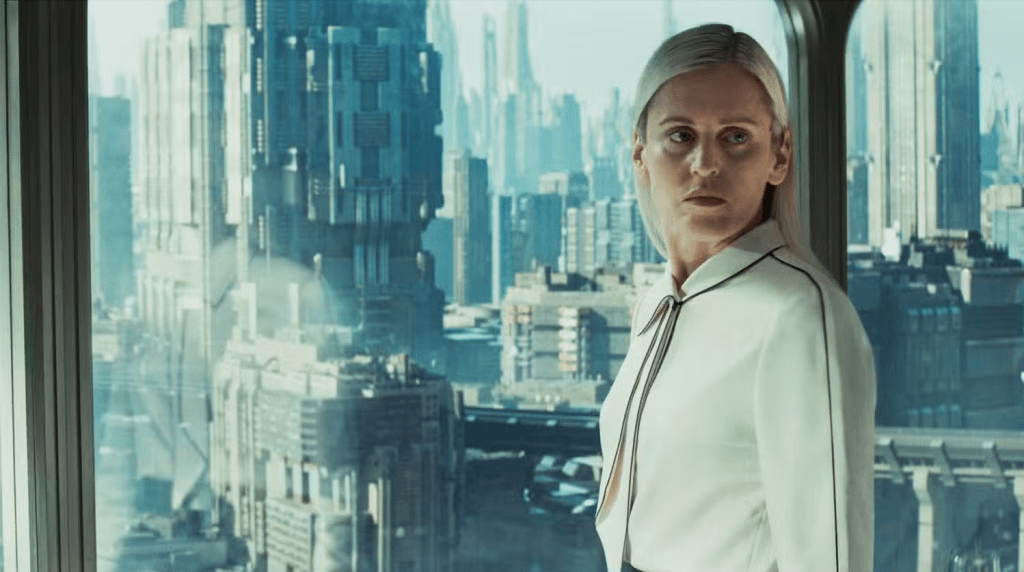

Those are the small touches, but season 2 hits the big notes superbly too. I was especially moved by the powerful and heartbreaking conclusion to Luthen’s story in the final arc, and with the expansion of Kleya’s character, so that she’s basically a main character by the end. Elizabeth Dulau is so stunning in the role (unbelievably, her first after acting school!), bringing out Kleya’s deep well of trauma and complex love for Luthen (not only her partner in crime but her father figure, as we come to find out) beneath her icy detachment and wonderful RBF.

Dulau was already stealing scenes in season 1 (no small feat when you’re playing off Stellen Skarsgård). Gilroy wrote a much bigger role for her in season 2 after seeing that she was “bulletproof” and could “do anything”; in interviews he compares her to Meryl Streep. I don’t doubt this will be Dulau’s breakout role and that she’s not going to be confined to Star Wars or the space-opera genre for very much longer; she’s too good. In season 2 she commands some of the most challenging and difficult moments of the series, much of it nonverbally, unexpectedly making Kleya one of the best characters in Star Wars history.

Kleya is everything I love about Andor — a new character with her own motivations, who has nothing to do with established lore, a total lack of fan service, and the way her severe attitude and awesome space-goth-glam wardrobe and makeup embody the dark, dystopian mood. All such a contrast to the things that don’t work about the season. In fact, that contrast exists overtly within the story, as the militant faction represented by Kleya ends up at odds with the Rebel command on Yavin who feel more like the old familiar Star Wars (not in a good way).

Going from being a supporting character in season 1 to being the best thing about the series, Kleya ultimately ends up at the emotional core of the story. Cassian’s climactic rescue of Kleya is what demonstrates his growth as a character in the end, even more than his loving but troubled relationship with Bix (which to be fair produces some of the seasons’s loveliest moments). Cassian’s character arc is about the journey from a refugee and hustler who puts himself first to someone who’s willing to fight for others and sacrifice himself for the revolution. This is not new; it’s a well-worn trope in the franchise all the way back to Han Solo, but as it does with so many Star Wars tropes, Andor deepens it and gives it more gravity.

So it’s really moving when Cassian receives a coded emergency signal from Kleya and sets aside everything — including Rebel discipline — so he can risk his life to save her in a harrowingly improvised extraction operation. It’s a fitting farewell to his character — not only a selfless action but his way of repaying everything Luthen and Kleya have done for him and for the Rebellion.

This is even more touching coming after the loss of Luthen (which Cassian only finds out about upon arrival at the safe house). Adding to this are the subtle parallels between the two: like Kleya, Cassian was orphaned by the genocidal destruction of his home planet. Luthen was something of a father figure for him too.

Because of the unfortunate prequel business, there’s a lot of weight put on the the fact that Kleya is in possession of intel about the Death Star (and this is no doubt what most fans will focus on), but the emotional bond between the characters resonates much more than the Star Wars lore.

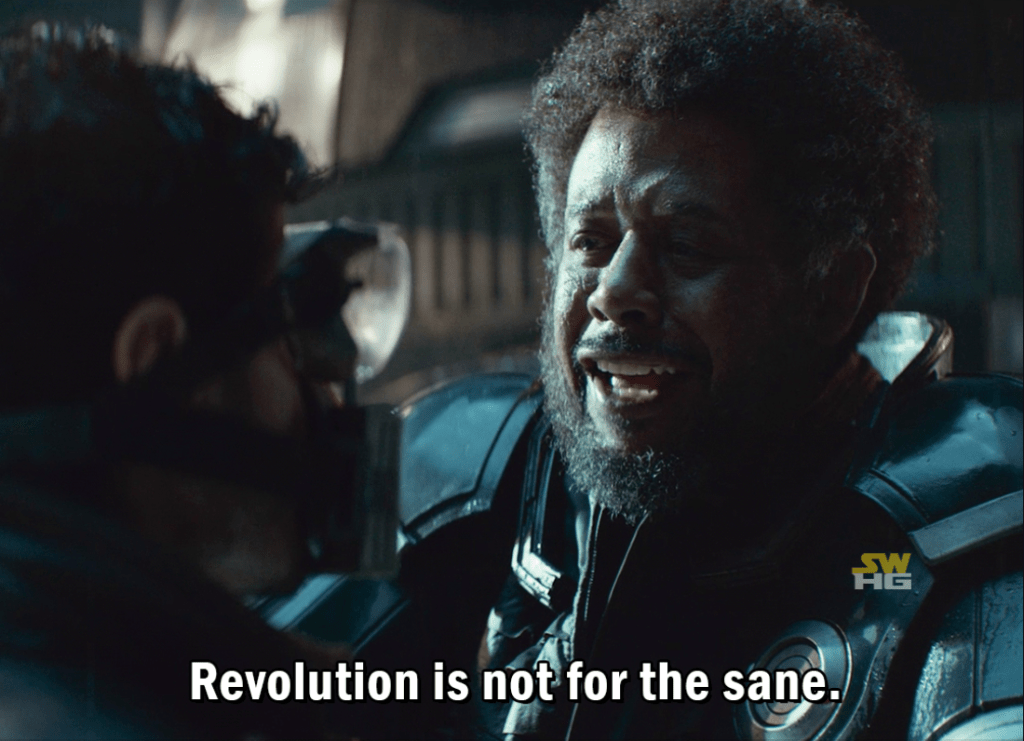

Andor is rightfully beloved for its great, almost Shakespearean monologues, and there are several more added to the series’ monologue hall of fame this season, including Mon’s antifascist speech and Saw Gerrera’s “Revolution is not for the sane!” rant. But for me, the exhausted, grieving Kleya opening the apartment door, clocking Cassian, and muttering, “It would be you, wouldn’t it?” is for all its brevity the best bit of dialogue in the season. It brought tears to my eyes.

The brilliance of Dulau and Luna in this scene is undeniable but it’s also par for the course. The acting is so good, from the stars to the bit parts (there are exceptions but I’ll get to that in the next article). I completely agree with everyone who’s saying that Luna and O’Reilly were robbed by the Emmys, but I would add Skarsgård, Dulau, and Denise Gough to the list. Reading interviews with Dulau and others, it’s obvious the cast felt a lot of investment in their beautifully drawn characters, and in Gilroy’s storytelling and what it brings to the franchise. This is mean, but it’s just funny to compare it to Harrison Ford phoning it in in Return of the Jedi because he didn’t want to be there.

You can’t understate the importance of the production design, by Luke Hull, to the success of Andor. The series is the most expensive Star Wars property ever; season 2 cost $290 million and the two seasons together a staggering $645 million. There’s a case to be made that Disney throwing these ludicrous sums around is bad for the film industry, as well as morally indefensible. Just speaking selfishly as a fan, I’m glad this one-of-a-kind series was the recipient of this bounty, and you can sure as hell see it onscreen. I wrote about the design in my piece about season 1, but Hull and his team really outdid themselves this season and it made for an even richer viewing experience. They’ve taken the aesthetic of Star Wars and made it more textured, lived-in, nuanced, and believable, not to mention more striking and attractive, and this really pulls us into the story.

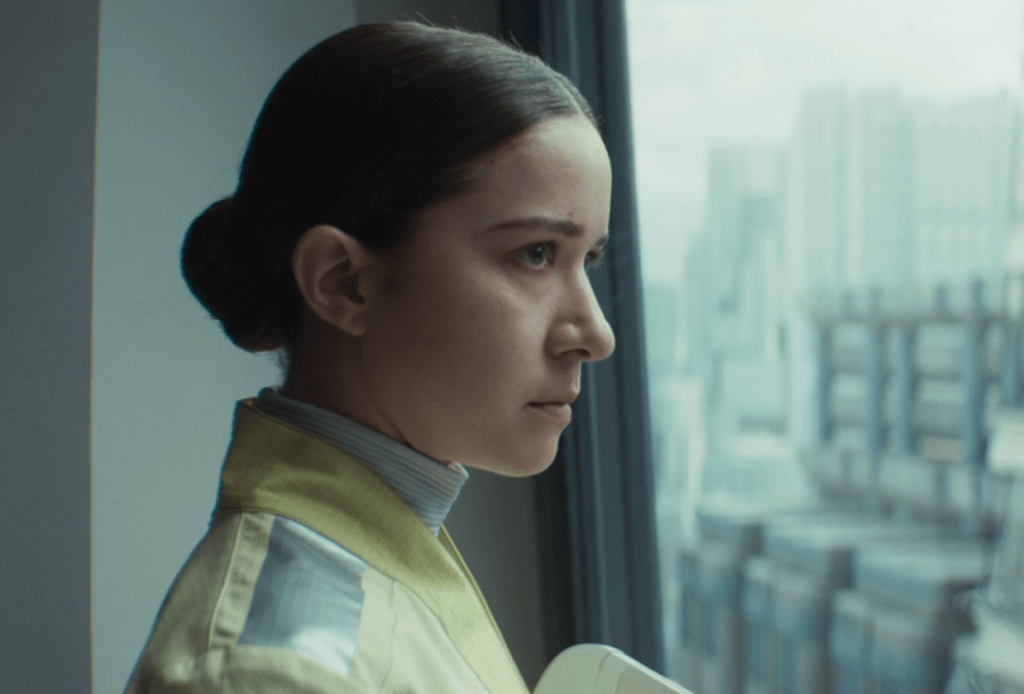

More than anything else about the season it was specifically the design that obsessed me for days and weeks at a time. Just look at the above still, set in the safe house on Coruscant. Everything: the lighting, the interior design of the apartment, the grime on the window, the brutalist cityscape in the background, the overcast weather. I love all the shots of characters pensively looking out windows throughout the series, and that it seems to always be overcast on Coruscant. It’s a whole goth mood.

There’s a richness to all the settings wherever the story takes us — for example the gorgeous wheat fields on Mina-Rau that make every shot look like Days of Heaven or an Andrew Wyeth painting. Star Wars has never looked this good. In that sense it can and should be counted as cinema, not just TV.

The design also serves as text or commentary on the story to an unusual degree. In particular the element of architecture is central to what the makers are communicating socially and politically.

Through a combination of terrific location scouting (such as the wildly futuristic City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, which didn’t need much in the way of dressing or effects to become the Imperial Senate on Coruscant), thoughtful set design, and handsome but unintrusive visual effects, the settings of Andor season 2 feel both alien and breathakingly real, like places you could imagine actually visiting or living.

Take the scenes set on Ghorman, a planet with an ancient textile tradition and industry, which feels to me like a cross between Turkey and interwar France (Hull says he was actually inspired by the architecture of Milan and Turin).

The design of the Ghorman-set scenes has a lavishness and warmth that gives a sense of proud history, wealth, sophistication, and centuries of stability — all of it doomed by the Empire.

By the way, I love that Ghorman culture, as storied and dignified as it is, is entirely based on spider husbandry! Check out the beautiful spider motifs in the café where Vel and Cinta meet.

This depth also applies to the wonderfully detailed Ghorman language invented for the series and made very believable by the supporting actors. The official materials call this “not just world-building, but culture-building too,” and Andor does it as well as any sci-fi or fantasy story I can recall outside of Tolkien.

“We built a whole Ghorman society,” Gilroy says. “It’s not just building the physical part of it. It’s building a culture…. We designed an entire aesthetic, and an entire language, and a cultural identity, and a national anthem, and a history.”

For example, the headquarters of the Ghorman resistance was conceived and designed by Gilroy and Hull to be the basement of a textile factory, with spinning machinery in the background and a workbench used as a conference table. It’s never mentioned in the screenplay, and few viewers will consciously make the connection, but it grounds the story.

It’s the kind of detail you don’t always get in sci-fi and fantasy — especially in this day and age when even expensive projects face rushed production schedules in order to meet the insatiable demands of streaming, and end up looking cheap and chintzy because the designers don’t have time to do their jobs. (I got into this problem in my review of Thor: Love & Thunder.)

There’s also a conscious effort this season to grapple with the design and architecture of fascism. I love the brutalist architecture of the Imperial capital planet, Coruscant. All the towering and sweeping grey concrete forms feel oppressive, even suffocating, but also grand and pretty, in a queasy way, like you’d expect from the architecture of an arrogant and troubled republic that fell into fascism.

I really enjoyed this video essay about the architecture of season 2. The creator, Morphologis (new to me), gets into the influence of Metabolism, a postwar Japanese architectural movement, on the modular design of some of the apartment buildings in the series, particularly Dedra Meero’s.

They argue that the modularity of the rooms relates to the fascist theme because it’s both seductive, in offering the dweller (or the viewer) a sense of strict, repetitive, comforting order; but also alienating because it does away with any individuality or quirkiness, making a home seem more like a prison cell. So Dedra (Gough) is, in the visual language of the filmmakers, imprisoned by the Empire as much as her victims are (and this foreshadows her own fate).

This is in contrast to the soothing old-money grandeur of the Mothma estate with its earth tones and feudal Japanese and Scandinavian motifs.

The scenes showing Cassian and Bix (Adria Arjona) living in the safe house on Coruscant are so weirdly relatable. It’s all too easy to picture living in a rundown concrete apartment block in a formerly middle-class neighborhood that has deteriorated into a slum after years of civic neglect, in the middle of a vast, grey city that’s the capital of an empire ruled by an oppressive authoritarian government, trying to cope with your trauma and with your future uncertain, but you still have to find time for your loved ones and for shopping and cooking dinner.

Here, the Empire is not just a gang of evil baddies, but a system, just like the system we live in. The government may be doing horrible things, and some of us may be trying to do something about that, but at the same time we also have to live our lives.

This is why Andor transcends Star Wars and is more comparable to something like Children of Men. Just to have a Star Wars series that shows apartments, and kitchens, and bodegas — complete with vegetables Bix has been meaning to try — is important to me in ways I can’t fully explain. The bodega feels so true to life; this scene made me smile.

In my first essay about season 1, I wrote that Hull’s design scheme “really explores this society that has interstellar travel and communication but seems limited to fairly primitive electronic devices, and gives it a visual logic.” I thought a lot more about this watching season 2, and it makes even more sense to me: the way advanced tech lives alongside more primitive elements in this galaxy.

This is not even a stretch; it’s very much like our world — the way you might have a solar lamp or a laptop with a frayed power cable sitting on a piece of furniture from the 1970s (I’m describing my writing station at home). The way there are both peasant villages and high-speed rail in China. The way the US is by far the richest nation on earth, but is also very backwards and crumbling at the same time. The Marxist term for this is uneven and combined development, and it’s never seemed more plausible in Star Wars.

Like what you’re reading and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee!

Michael Wilkinson’s costume designs integrate into Hull’s visual scheme so well, managing to seem both practical and fabulous at the same time, exactly the fine line you want in an epic space adventure that’s so relevant to our world.

It’s too much for me to get into a lot of detail about the costumes, but I love so many of Wilkinson’s choices, such as the way the soft yellow hospital scrubs contrast with the brutalist grey concrete and drab institutional interiors…

…and the dark blue motif several of the Rebel heroes, including Cassian, Mon, and Kleya, break out when they have a reason to dress up.

One of the best things about season 2 is the way Gilroy incorporates more satire and even camp this time around, pushing back against the perception that Andor always has to be “serious.” I’ve already mentioned the camp of Mon’s cathartic boogie. Season 2 also gives Luna a chance to be fabulous when he’s assigned to pose as a fashion designer on an undercover mission. Watching Cassian Andor strutting and slaying, albeit in disguise (obviously he learned how to slay this convincingly somewhere!), it’s clear they’re poking fun at our perception of the character, and it’s wonderful.

The unsettling scene in which Imperial leaders plan the genocide of the Ghor — overtly referencing Nazi history down to the resemblance of the setting to the Eagle’s Nest (this is covered in Morphologis’s video) — also features a laugh-out-loud parody of educational cartoons.

Some of the funniest and most unforgettable scenes are those in which Dedra and Syril Karn (Kyle Soller) host Syril’s mother Eedy for dinner at their apartment. The almost violently uptight Imperial supervisor and the clueless social-climbing bureaucrat, with their not-so-subtly dominant-submissive relationship, straining to seem like a normal domestic couple under the judgmental gaze of the pretentious and impertinent middle-class mother in their sterile modular apartment — here, Andor becomes a sitcom about life in a fascist society.

These welcome shifts in tone made me realize that taking Andor too seriously is a little silly. We are, after all, still in the realm of galactic intrigue and laser guns. It’s still fundamentally a space opera, despite the more dramatically weighty and politically relevant approach, and it’s only right that there should be some camp at the heart of it. There’s a difference between being darker than other Star Wars entries and being no fun.

There’s a loopy set of scenes in the first arc in which Cassian is marooned on a jungle planet that we only later realize is Yavin 4, the future location of the Rebel base. At this early stage it’s just a hideout for the Maya Pei Brigade, a desperate, half-starved band of guerrillas with low morale and worse discipline. When Cassian brings the stolen TIE avenger to the prearranged rendezvous point, the paranoid guerrillas take him prisoner, not believing he’s a fellow Rebel, and then splinter into bloody factions arguing over the bogged Imperial fighter.

A sublimely entertaining farce ensues, as the increasingly deranged mob bicker like children, threaten each other, fend off attacks from wild-boar-like creatures, and gag on a disgusting durian-like fruit that’s their only hope of survival, all while the subdued Cassian watches on in bemused horror. One faction takes control of the fighter, but they have no idea how to operate it except to fire its blasters. They set themselves to moving it into position like a cannon to blast the other faction’s barricaded hideout, only to discover that the massive fighter, nimble as it is in the air, is impossibly heavy to move by human hands while stuck in the mud. Dozens of them sweat and strain over it, taking hours to change the angle a few centimeters, as if they’re moving an ancient monument.

The tactility of these scenes is something else — the grime, the humidity, the tension as the other faction tracks their progress from afar, the fact that the sheer weight of this piece of military hardware (normally so fragile and disposable in blurry FX sequences) is now an important plot point. It’s so funny and weird yet so riveting, like a cross between Apocalypse Now and Fitzcarraldo. It’s completely unlike anything the franchise has ever given us — or will ever give us again, I suspect. That this misadventure moves the story forward only obliquely is even better. In deliberately testing our patience and undercutting all our expectations of who the Rebels are, while toying with the iconic imagery of the franchise, it’s basically a satire of Star Wars itself.

Arc 2: The politics

Going into season 2, I was worried that the left-leaning politics that made the first season so memorable would be dampened or downplayed under pressure from Disney in this atmosphere of reactionary backlash. After all, the company cancelled the Black-and-queer themed Star Wars series The Acolyte, in part to appease the toxic chuds who predictably brigaded against it; while Disney-owned Pixar has announced that it will move away from telling more “personal” stories like Turning Red (“personal” in this case meaning “Asian”).

I was delighted to find that not only was there no reason to worry, but Gilroy and company seem to have made a conscious decision to double down on the politics this season. So there’s a lot to unpack — and I do have mixed feelings about a few of the political angles, too.

I was really impressed with how the scenes on the farming planet Mina-Rau foreground the issue of migrant labor and borders. Bix, Wilmon (Muhannad Ben Amor), Brasso (Joplin Sibtain) and several other Rebel comrades who escaped Ferrix after the uprising there at the end of season 1 are employed as laborers in the vast wheat fields of Mina-Rau as they hide out from the Empire. They live in constant fear of questioning or arrest if their undocumented status on the planet is discovered.

How deep does that cut right now? All the anxiety over visas and audits and Imperial raids — it’s not subtle. The raid on the farm and the troopers’ terrorizing of the workers seem ripped from the headlines.

This is true of other scenes too: for example, the way the ISB thugs wear partial stormtrooper armor in the raid on the safe house makes them look so much like ICE agents. It’s such an interesting remix of Star Wars iconography. I mentioned in my first essay that the way Andor depicts stormtroopers as cops is one of its most direct political commentaries.

And yet this season was written and produced during the Biden administration. It just goes to show you that the current crisis has been building for a long time; it’s not just Trump’s doing. Biden increased ICE’s funding, refused to close Trump’s concentration camps, and deported people at a higher rate than any president besides Obama. Obama himself is infamously remembered as the “Deporter-in-Chief”; he greatly expanded the Department of Homeland Security and ICE after George W. Bush founded them. We wouldn’t be in this situation without the Democrats.

Anyway I’m not surprised that Gilroy has a broader and more sophisticated view of the US border regime than simply blaming Trump. This is a systemic problem, and it’s not limited to the US: “Fortress Europe” is responsible for some of the most horrific oppression of immigrants in the world today.

They get every detail right here, like the way the dialogue makes it clear that the farmers on Mina-Rau, the breadbasket of the Empire, depend on undocumented labor for their production and profits. The Empire knows this, and yet they crack down on it periodically anyway. This keeps the workers living in fear and prevents them from demanding their rights: exactly how it works in real life.

It also makes sense that many of the migrant workers, including Bix, Wilmon, and Brasso, are played by Black or brown actors, while the farmer and his family are white, almost resembling white settlers in South Africa or Israel. That was a deliberate choice, I think, to reflect real life — for the same reason Luna’s Mexican heritage and accent makes his backstory as a refugee (which you’ll recall was Luna’s idea) that much more tangible.

If anyone tried to convince themselves that racism as we know it doesn’t exist in Star Wars (after all, nobody refers to Lando Calrissian’s race) — well, George Lucas intended from the beginning for the marginalization and exclusion of droids to resemble Jim Crow segregation. Star Wars has always commented on racism. It may be a galaxy far, far away, but unlike Star Trek, it’s not more progressive and utopian than our world; it reflects the same social problems as ours. Women are oppressed just like they are in our world, for example.

At the same time, these movies and series exist in our world (as much as the toxic fanboys furiously deny it), so there would be subtext to Lando’s and Cassian’s and Rose Tico’s identities even if it hadn’t been explicitly intended.

I have contradictory feelings about Bix being sexually assaulted by an Imperial officer during the raid — the first depiction of sexual violence in Star Wars history. Of course sexual violence is an inherent part of border regimes and the oppression of women workers, so it very much goes with the theme. I see what they were trying to do, and I thought it was good that Bix actually says “He tried to rape me.” Saying that out loud is a bold choice for Star Wars. But since she was also the victim of torture by the Empire in season 1, it just veers a little too close to exploitation for me. My partner wasn’t keen on it either; I felt her stiffen next to me during this scene, and again during the later scene in which an enraged Syril chokes Dedra.

About that latter scene: I believe the purpose is to depict, and critique, toxic masculinity. Like many real-life men who embrace fascist ideas, Syril feels he’s been let down by life, and by the system. This is reflected in all the angst he feels over impressing his mother and in having a respectable job. He desperately wants to be an important man in the Empire, but he discovers that his partner, who holds more power than he does, has callously used him as a pawn in a covert operation. So he lashes out with violence against her, as men often do to women close to them.

It’s an ugly scene. It’s meant to be an ugly scene, and I laud the writers for trying to do something complex here — but still, I didn’t feel super comfortable about it. Are we supposed to be blasé about a man choking a woman onscreen because they’re both villains?

Apparently some toxic Star Wars chuds are coming to the exact wrong conclusions about this scene, which is not at all surprising. Not that you should let the vileness of the manosphere keep you from critically depicting abuse. I don’t know what the solution is, but I understand why more and more women, including my partner, don’t want to see depictions of violence against women onscreen for any reason, valid or otherwise.

One thing about the politics of season 2 is the sidelining of mass movements, and specifically workers’ movements, compared to season 1. Whereas the prison riot and the general strike and uprising during Maarva Andor’s funeral are the climactic and definitive moments of the first season, here there’s really only one sequence that depicts the masses in motion, the protest on Ghorman — and that ends in a massacre. The rest of the season is devoted to espionage and guerrilla warfare, and thus, politically speaking, lends itself to substitutionism, the idea that the actions of a few determined militants can replace those of the masses.

This is nothing new to Star Wars — Lucas’s original inspirations were the guerrilla fighters of the Viet Cong. In general, Maoism, with its excessive focus on guerrillas instead of mass movements, was a dominant influence on the radical politics of Lucas’s generation. It’s just somewhat of a disappointment to revert to this in season 2 after the very sharp, mass-oriented politics of “One way out!” and “Fight the Empire!” which were largely new to the saga.

In fact, at times season 2 seems to be suggesting that mass protest is bad. There’s a murky subplot about the Imperial conspiracy to manipulate the Ghorman resistance so they can portray them as terrorists. This culminates in the sequence in which Imperial snipers fire into the crowd at a peaceful protest, turning it into a riot and bloodbath and scoring the needed propaganda points to justify genocide.

I’m still not clear on this, but some of the dialogue seems to suggest the protest was misguided and the Ghorman resistance walked into a trap. This plays into all kinds of real-life paranoia on the left about the act of protest in an authoritarian society. Some leftists actually think protesting is unsafe, whereas in reality it’s much more dangerous in the long run not to protest authoritarianism. Indeed, during the anti-ICE uprising in Los Angeles, I saw many online liberals and leftists comparing it to the Ghorman massacre in Andor — in other words, saying the protesters were giving Trump the excuse he needed to declare martial law in California. This irritated me for two reasons.

Yes, you should throw rocks at ICE agents whenever you get the chance, no matter what Donald Trump is planning; and yes, protesting in their thousands is exactly what the Ghor should have been doing, even if the Imperials were scheming against them. Sometimes you have to take your stand even when the odds are stacked.

I’d like to think the writers intended to show a justified protest that was opportunistically exploited by the fascist enemy, rather than one that was manipulated from the start. I’ll have to rewatch the season and see if I can parse this more.

These reservations aside, the massacre sequence itself is masterful. The episode’s director, Janus Metz, and editor, John Gilroy (Tony’s brother), create such a complex mood of mass anger and the euphoria of protest combined with suspense, claustophobia, and dread. As the crowd in the plaza swells, the various characters including Cassian, Wilmon, Dedra, and Syril navigate in and out of it with their various agendas, and the Imperial troops slowly kettle it, preparing for attack.

Hollywood rarely gets the feeling of being in a large crowd right, but this episode does. As someone who’s been to a lot of protests, it felt pretty real, and that enhances the horror when the violence starts.

There’s political value in these filmmaking choices too: we see the crowd as human beings with a legitimate cause, not a blurry, indistinct angry mob of extremists, as the real-life news depicts most protests; and when the stormtroopers start firing into the crowd, it’s that much more shocking.

This sequence strongly reminded me of Peterloo, Mike Leigh’s 2018 fictionalized account of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, a pivotal moment in British history and for the left worldwide.

Like its fictional counterpart on Ghorman, the Peterloo protest took place in a large urban square in Manchester, where an unarmed crowd of 100,000 men, women, and children protesting for more democratic rights were viciously attacked by army cavalry and local yeomenry at the behest of the city’s ruling class. Eighteen people were killed and 700 were injured.

Loach’s film accomplishes the same thing in humanizing the assembled masses and in making the protest and violence so vivid and breathtaking.

Knowing Gilroy, these allusions were intended. For one thing, the cloth banners of the Ghorman protesters very much resemble the ones at Peterloo.

These scenes also clearly borrow from one of the greatest pieces of leftist filmmaking of all time, the famed Odessa Steps sequence in Soviet director Sergei Eistenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). The stormtroopers descend the steps of the plaza, menacing and then attacking the protesters just as the Tsarist troops do in the silent classic.

(There’s no pram involved this time, but it’s a far more politically relevant tribute than the one in Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables, in which the FBI are the good guys.)

The next episode after the massacre is spine-tingling in the way it parallels real life, with Mon and Bail Organa (Benjamin Bratt) discussing the news of genocide they’ve seen coming out of Ghorman in hushed, horrified tones, just like we all do about Gaza now.

Then we see Ghorman’s Senator Oran (Raphael Roger Levy) arrested by stormtroopers and dragged away. This moment is one of those that took on greater significance because of its eerie resemblance to the brutal forced removal of Sen. Alex Padilla from a Homeland Security press briefing the very same week it aired. Gilroy spoke about that at an industry conference the other day: “Our internal chat group is like, ‘What the fuck?’ … Things were fomenting as we’re going, but the detail with which the world has just grafted onto our show and started replicating what we were doing is incredibly sad and shocking to us.”

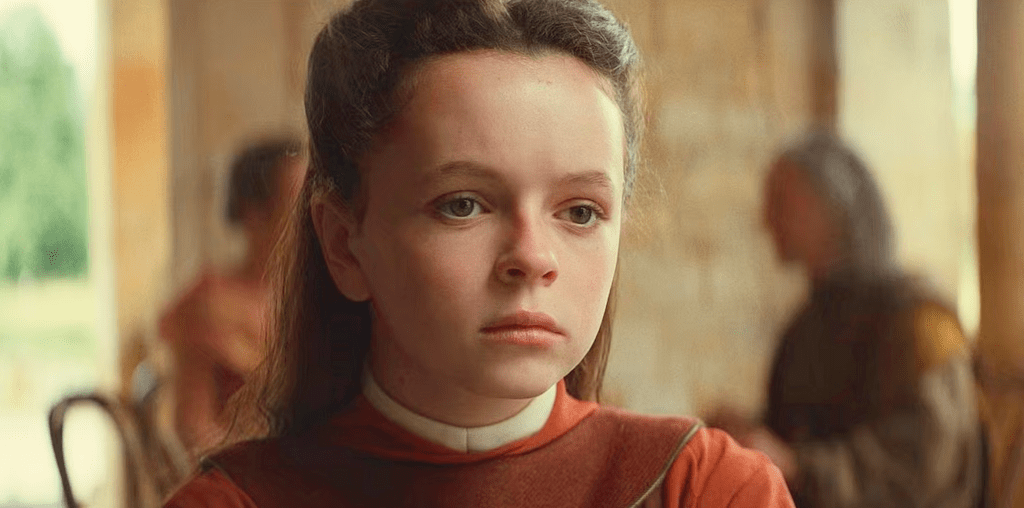

Another sequence that’s a painful reminder of current events is the one in which we find out Kleya’s backstory. She survived the Imperial genocide of her people when she was a little girl (played by April V Woods), and was rescued by Luthen, a sergeant in the Imperial army who quit and vowed to fight the Empire after seeing his own troops slaughtering children. Watching the soldier’s and the young girl’s traumatized reactions as we hear the screams of children in the distance is queasy to say the least in 2025.

In this context, Mon’s speech denouncing the Ghorman massacre is so powerful, especially for the fact that she calls it a “genocide — yes, genocide!” This is remarkable on two levels: not only has that word never been used in Star Wars, as far as I know, but how many politicians in the world today would be this brave and speak with this much clarity right now?

Given all that’s happening, it’s no wonder this fictional speech went viral, just as Karis Nemik’s manifesto went viral after season 1, and of course, O’Reilly’s delivery of the speech is magnificent (looking at you, Emmy voters).

The distance between what is said and what is known to be true has become an abyss. Of all the things at risk, the loss of an objective reality is perhaps the most dangerous. The death of truth is the ultimate victory of evil.

Gilroy says there are a number of influences on the speech, including a direct nod to Abraham Lincoln, but this quote from Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism struck me with its obvious parallels:

The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced [Stalinist], but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.

Although I think it’s corny to compare Trump to the Emperor, and although as a Marxist I argue against the idea that the US has descended into actual fascism (prematurely diagnosing fascism is not only shortsighted but also politically harmful), I think it’s fantastic that people are taking these themes and running with them, deriving inspiration and hope from them. I think that’s what Gilroy intended.

Gilroy regularly deflects when asked about the show’s commentary on Trump or Gaza. “I’m not psychic,” he told the Hollywood Reporter in May (“a bit wearily,” the writer adds). He repeats over and over that Andor is based not on current events but the fight against injustice throughout history, and that the reason it seems so on the nose about Trump and Gaza, despite being written and filmed two years ago, is that historic patterns are repeating themselves again.

True enough, and it goes to show that a keen study of history will naturally give you more clarity about current events. But at the same time, I’m sure some of this is Gilroy politely equivocating a bit while representing a Disney property in the mainstream media. You can’t tell me that this searing portrayal of a revolution against fascism, in which the word “genocide” is used quite bluntly during a climactic speech, didn’t have some level of intentionality on the part of the creators as it completed postproduction in early 2025 and was rolled out with all these nightmares unfolding.

Something tells me Denise Gough wouldn’t argue:

Whatever Gilroy’s intentions around today’s headlines, he’s clear about the show’s revolutionary ideas, and using Disney’s money to broadcast them. “I’m fascinated by revolutions,” he says. “If I tried to sell a movie script about a young revolutionary dying for the cause, no one’s going to back me… But if you tell it as Star Wars, you have a place to play.”

One of the best aspects of the series’s portrayal of revolution is the way it shows the conflicts, disappointments, and even the betrayals of revolutionary organizing. After Mon makes her speech and flees the Senate, she’s whisked away to Yavin by Bail Organa and installed as the Rebel leader. This is a political maneuver, a fait accompli that undercuts Luthen’s control of the Alliance even as it’s finally ready to come out of the shadows and unite the galaxy’s dissidents against the Empire. After sacrificing everything to build this organization from scattered bands of militants who didn’t even know they had allies, Luthen has increasingly been regarded as a relic of the Rebellion’s murky and morally dubious past, if not a dangerous liability.

This points to the historic tension between reform and revolution within the Rebellion. Recall how Mon, the wealthy bourgeois politician who at first campaigned for legal solutions to the Emperor’s outrages, was horrified when Luthen organized a “terrorist” attack in season 1 with the funds she secretly transferred to him. Though Mon has come over to the need for armed resistance, perhaps there remains within the organization a political struggle over their ultimate goals. Reading the text with a Marxist eye, Mon might represent a fictional version of liberal or reformist factions in historic revolutions such as Spanish Civil War — fighting a revolution merely to restore the capitalist republic instead of creating a new and socialist society.

Cassian finds himself pulled between these factions as he tries to figure out how much he’s willing to give up for this struggle. This is the emotional as well as the political significance of his unauthorized and dangerous mission to rescue Kleya.

It’s all so thorny and complex, not to mention bitter and melancholy, compared to anything else in Star Wars, but this is how revolutions play out in real life. Gilroy, the student of history, makes sure to haunt us with that lifelike quality alongside all the thrills.

Amid all the other poignant references and allegories this season, the thing that quietly hit me hardest as a leftist is when Luthen says, “We fight to win. That means we lose, and lose, and lose, until we’re ready.” I just love this because it’s so true of real-world revolutionary organizing: if you’re in it for the long haul, you have to accept being marginalized and scorned and losing for a long time.

It’s a much more powerful statement than “Rebellions are built on hope,” which has become something of an informal tagline for the series and which is a bit generic and cheesy in my opinion. Of course that line actually derives from Rogue One and when it’s repeated here it’s meant to foreshadow that film. If you ask me, this overweening dependency on Rogue One is the source of most of the weakest aspects of Andor season 2.

And, as I said, I’m going to need a whole other article to get into all that. Stay tuned!

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!

Feature image: Diego Luna in Andor season 2 (2025). Image credit: Lucasfilm

3 thoughts on “Andor season 2 is revolutionary TV”