This is the second part of my two-part deep dive into Andor season 2. The first part, which I posted last year, covered the cinema and politics of the latest and final season over two sections or “arcs” (named after the show’s unique three-episode narrative blocs). Here, in the third arc, I take a look at some of the weaknesses of the series finale, especially regarding what I call “prequelitis.” This is when franchise prequels sacrifice suspense, drama, and character development in favor of unnecessary exposition and fan service while “funnelling” into established lore.

In case you’ve landed on this piece without having read the first one, I recommend you go back and do that. Not only so you have a broader understanding of my view of Andor, but also so you know my complaints are far outweighed by the things I love about this wonderful series. To be clear, Andor is one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen, and as I mentioned in my last piece, the crowning achievement of the Star Wars franchise. My critiques are coming from the highest expectations; it’s tough love if you will.

Warning: There are lots of plot spoilers below for Andor season 2.

Taking issue with the ending of the series is not a popular position in the Andor fanbase. Most people I’ve seen commenting on it, either in my circle of friends or in fan forums, loved the finale, or at least didn’t overthink it. I’ve talked to a few who agree with me, so I know the naysayers are out there. The reason I overthink it is because to me the ending betrays specific aspects of the series that make it so special. It also points to larger problems with storytelling and cinema literacy in the age of franchise media.

Some fans don’t want to hear anything bad at all. When I mentioned my problems with the ending in a Facebook group for fans of Rogue One and Andor, one commenter accused me of “fault-finding a masterpiece.” I find this strange. I don’t see what’s wrong with critiquing something even if you love it. In fact the more I love a movie or show, the more likely I am to think about what could have been better, or to spend time teasing out its good and bad politics (I wrote a whole article about the flaws of Return of the King, a movie I love to death).

It’s too much to get into all my thoughts about Star Wars stan culture here. Many fans, especially the more progressive ones, actively embrace everything the franchise has ever done — the cheesy prequel trilogy, the divisive sequel trilogy, everything — as a defense mechanism against the haters who’ve made the Star Wars fandom notorious as the most toxic in existence. Criticism is associated with the trolls and ragebaiters and often seen as problematic.

I understand the desire for positivity and tolerance amid the nightmare of the Star Wars culture war, but still, I feel less in common with the stans and more in common with Jenny Nicholson. Nicholson is of course one of the more high-profile Star Wars fans on the internet, especially known for staunchly defending The Last Jedi through the worst of the backlash. But she was let down by The Rise of Skywalker and was brutally honest about that in her review (I got into this in my recent piece about Nicholson).

Like Nicholson I have a dual perspective as a fan and critic. Star Wars changed my life as a kid, as it did and still does for so many others. It gave me a pathway to a lifelong love of cinema. But it’s also a really weird and hokey franchise that sometimes brings out the worst in people, and I’ve often been embarrassed to admit I’m a fan (at least until Andor came along). When it falls short I’ll say so; if you ask I’ll tell you all about why Return of the Jedi is a very uninspired and disappointing conclusion to the original trilogy.

All this is to say that if you don’t like it when Andor is criticized even in good faith, this is probably not the article for you!

Arc 3: The letdown

After the lights-out brilliance of the first two arcs of Andor season 2, the first thing that seriously disappointed me was the moment midway through the season when Cassian (Diego Luna) is approached at the Rebel base on Yavin by a “Force healer”(Josie Walker) — a Force-sensitive person (as distinct from a Jedi) who seems like some kind of itinerant psychic. She admits to not having much of a handle on her own limited Force powers but tells Cassian that she senses he has a great destiny to fulfill, and even bursts into tears, seemingly overcome by what she feels in his presence.

I audibly groaned during this scene, and not only because it’s so uncharacteristically corny. I felt it was a betrayal of the entire point of Andor. As I wrote two years ago in my essay about season 1:

Andor leaves the Jedi out is so it can leave the Force out. The idea of a mystical, all-enveloping supernatural power really has no place in a more realistic story about a people’s revolution. This brings the franchise closer than ever to a materialistic view of the universe. Materialism is the realization that our material conditions are the cause of our social conditions, and that material struggle is the only way to improve those conditions — the only way to change the world (or the galaxy). Not morality, not individual self-improvement, and not anything mystical or spiritual or external to the physical world…

Andor makes a welcome break with all that because it’s much more directly about our world and the problems and injustices we face for real. For it to really resonate as a story about revolution it has to be about the solutions to those problems that humans can come up with ourselves, by working together.

Were we suddenly supposed to believe that Cassian isn’t the roleplayer established in season 1 — someone who joins the Rebellion based on his own difficult and traumatic life experiences, with the help and encouragement of others along the way — but that all this has happened because he has a destiny? I could even picture some fans speculating that Cassian is somehow a Jedi without knowing it.

Thankfully the Force is never mentioned again, and in retrospect I may have been overreacting a bit. It’s not that I never want to see the Force in Star Wars again. I love the way The Last Jedi explores and reinterprets the Force — I love that beautiful montage when Luke teaches Rey to feel the life and death and the flow of everything around her. Later, Luke Force-projecting himself onto the battlefield at the climax is hands down one of the coolest and most emotionally resonant moments in Star Wars history.

Star Wars is essentially a fantasy, and knocking a fantasy because it fails to uphold a materialistic view of the universe is unhelpfully rigid, a classic fallacy of the left, and just no fun. A comrade pointed out that in this fictional galaxy, the Force is material reality, and actually represents the collective, because it’s said to bind everything and everyone together. I love that way of looking at it. And I suppose it’s natural for the writers to want to establish that one subtle connection to the rest of the saga.

At the same time, I really enjoy Andor not having the Force in it because it’s like a storytelling experiment: What if Star Wars without the Jedi? I think it’s a really interesting and valuable way to rethink this fictional galaxy, even if we don’t have to attach it to materialist politics. In the end, I’m grateful they didn’t set that experiment aside apart from this one weak scene.

I found the scene in which Cassian discovers Bix (Adria Arjona) has left him so tonally awkward. Her recorded goodbye sounded so much to me like a suicide note I assumed that’s where it was going — after all, Bix did suffer devastating trauma as a torture victim in season 1, which led to drug addiction as a coping mechanism early this season. Was it originally intended as suicide in an early draft of the screenplay, and later softened, but with the same emotional beats in place? I don’t know, but either way it doesn’t really work for me.

It also seemed like the writers were disposing of Bix, one of the strongest characters in the series, simply because she isn’t in Rogue One — in other words, the prequelitis beginning to impact the story. Of course nearly everyone in the cast (aside from Cassian and Mon Mothma) has to be “disposed of” one way or another before the end for this reason, so it doesn’t top my list of complaints. And I admit that heartbreak does add emotional depth to Cassian’s growth as a character. But still, it vaguely irritated me because I wanted Bix to be more of a factor in the finale instead of just ghosting like she did; and it felt a little bit like the conclusion of her character arc was simply to serve his.

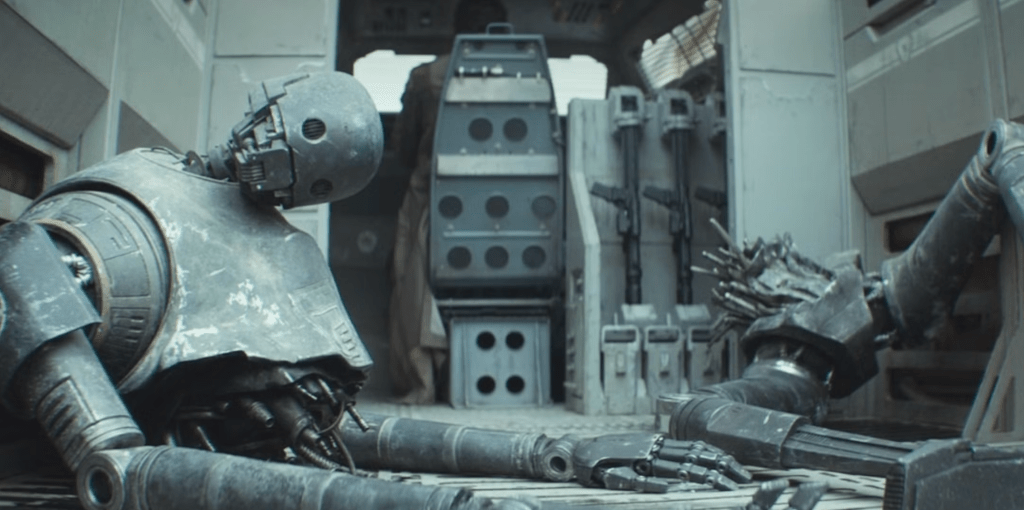

The most glaring instance of prequelitis before the finale is when K-2SO is introduced during the Ghorman massacre sequence. This is just really basic fan service, and it’s so distracting and uninteresting amid this otherwise powerful, wrenching, and politically sharp sequence. I like K-2SO all right as a character, but I don’t need to see his origin story. In Rogue One, when K tells Jyn that he’s a reprogrammed Imperial droid, imagining all the ways that could have come about is part of the fun. Seeing it actually happen subtracts from that enigma.

It irritates me that this origin story will inevitably spark more conversation among the fanbase than the massacre itself.

Sadly there is worse to come. In my review of Andor season 1, I coined and described the “funnelling effect” — the very annoying tendency of modern prequels to exhaustively set up every last detail of the original installment, bottlenecking the narrative to the detriment of everything else. It’s relevant to point out that Rogue One itself is one of the arch examples of this syndrome, with all the tedious and unnecessary business setting up the first Star Wars. Going into Andor season 2, I feared this would be a factor. In fact I called it at the end of that piece, which was written over two years before season 2 premiered: “I’m extremely psyched about season 2, but I do worry it will give in to that funnelling tendency — if for no other reason than it will be that much closer to established timelines.”

Well I was right, and I hate it. After Cassian rescues Kleya (Elizabeth Dulau) from the safe house, the last episode completely drops all the suspense. This happens so abruptly it’s almost a physical letdown after the extreme tension of the previous scenes. K-2SO as the deus ex machina (or I guess the machina ex deus in this case?), rampaging through the Imperial cops with no trouble at all, makes us feel almost silly for being so invested in the outcome. It’s an apt visual metaphor for Rogue One imposing itself on Andor.

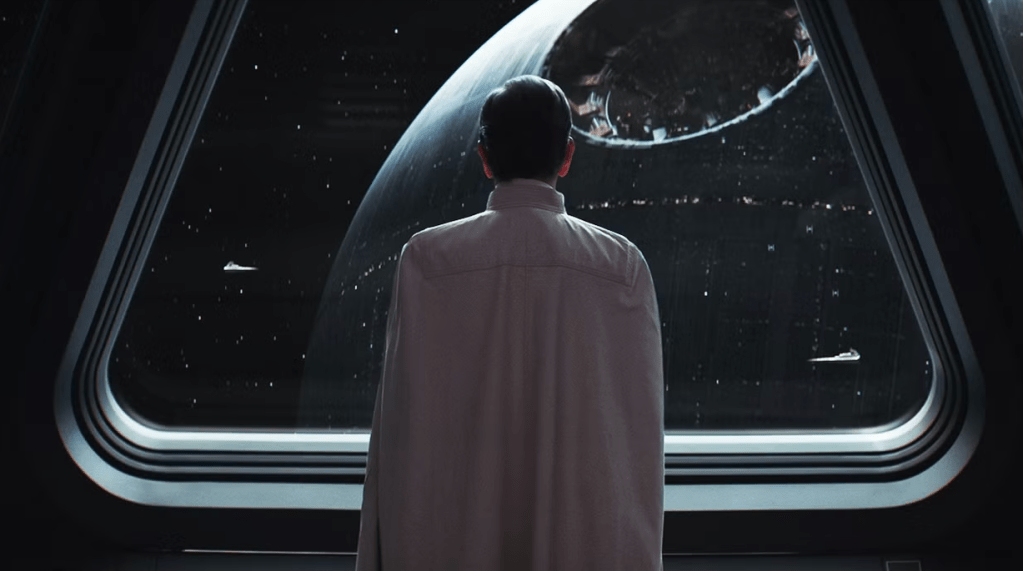

Then we go back to the Rebel base on Yavin for a very mechanical setup of Rogue One that drains what interest remains out of the story. There’s no tension in the final scenes at all, and not much dramatic payoff. It basically functions as a long trailer for Rogue One.

When did we decide this is what prequels have to do? I’d have to comb through movie history to be sure, but my operating theory is that Revenge of the Sith is to blame — that’s the first film I remember doing this shit, and I hated it then too. If so, it says a lot that the bad Star Wars prequels are to blame for this dumb convention.

I don’t need to see the actual handover of the Death Star plans to a CGI zombie Carrie Fisher. I don’t need to know why Natasha is blonde and wears a vest in Infinity War, as Black Widow pointlessly takes pains to explain.

I didn’t get time to write about Furiosa in these pages but I’ve thought about it a lot, especially as one of the most troublesome examples of prequelitis in recent years. It’s watchable enough for much of its runtime — George Miller couldn’t make an outright bad movie if he tried — but as the first-ever Mad Max movie that’s not utterly scintillating, it’s very disappointing too. It especially lands with a thud at the end, because sure enough, it feels the need to funnel lamely towards Fury Road. I really don’t care how the Organic Mechanic came to work for Immortan Joe! We already know Furiosa snuck the Five Wives into the War Rig, we don’t need to see it happen onscreen!

All this is an insult to the viewer’s intelligence, and tarnishes the legacy of its vastly superior predecessor. Anya Taylor-Joy, one of the best and most interesting young actors of today, is quite good in the title role, but the closer it gets to the end, the more she’s mired in an impression of Charlize Theron, almost a parody of her. Interpretation isn’t allowed anymore in franchise media; actors and filmmakers are no longer allowed to try new things with established characters. They must look and dress and act the same, or apparently the fans will revolt. This has flared up into a controversy lately with all the casting and costume decisions of the upcoming new Harry Potter TV series, which seems set to ape the Chris Columbus adaptations to the point of caricature, as if it were a theme park instead of a new take on a familiar story.

I will never understand why fans of genre cinema demand this extreme literalism, this pedantic grocery list of things to tick off to make them more comfortable about the conclusion of a prequel. Imagine if the last 40 minutes of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom had been devoted to setting up Raiders of the Lost Ark — all the things involved with getting Indy to Peru to hunt for the gold statue. Can you see how lame and devoid of storytelling value this would be? Yet this is what all prequels do now.

Once again: I don’t need to know every little thing that transpires before Cassian leaves on the spy mission that opens Rogue One, down to the minute. Those last shots with him getting on his ship, walking in slow motion with the music swelling, made me so impatient. After it dragged on for a while, my partner and I ended up laughing out loud. After two seasons of the best TV I’d ever seen, that was painful.

It’s so cheesy and dull. It’s the death of suspense, the death of storytelling.

It’s also completely contrary to everything that makes Andor great. It betrays that writing economy, that ambiguity, and that trust in the audience. It short-circuits the great character development and political themes. It’s so hard not to make the comparison between this clunky conclusion and the season 1 finale, which was about a general strike and uprising against the Imperial troops of Ferrix, and has so much taut drama and so much to say about our world.

It’s also hard not to think of all the heights the series achieved earlier this season. I was not surprised when I read that Janus Metz, the director of episodes 7–9, which feature the Ghorman massacre and Mon’s escape from the Senate, was advised by showrunner Tony Gilroy to avoid watching other Star Wars entries before production. Owing very little to all the tropes and canon — the muck of the Star Wars ages — while serving as a powerful analogy for real-world social struggle is why those episodes in particular, and Andor in general, work so well. It’s too bad they lost sight of this at the very end.

And here’s a big part of the problem: Rogue One is very overrated! I have a problem with the funnelling in the first place, but it’s funnelling into an overrated movie, itself a prequel that funnels into another established story, and that makes it doubly annoying.

I touched on why I find Rogue One overrated in my review of season 1, but after rewatching it upon finishing Andor, as many fans have done this year, if anything I’ve downgraded it. I really resent its sway over the fanbase. I’m glad to have Jenny Nicholson on my side because otherwise I feel like a crazy person whenever people call it “the best Star Wars ever,” which is often. Nicholson is so right about how incoherent and self-indulgent it is — how it features almost no character development at all, and how it purports to be dark, but isn’t really, because all the dying is actually presented as noble and beautiful. “That one senseless death in The Good Dinosaur makes it a darker movie than Rogue One, which according to you guys makes it a better movie.”

She’s also very scathing about the Darth Vader fan service that completely undercuts the narrative:

This is the worst thing: Why was Darth Vader at the end? You know that movie Glory, where everybody died to support a larger cause? So what if in Glory, after everybody dies, they have an extended sequence where a super buff Confederate soldier walks out, and it plays cool music, and the Confederate soldier just starts slicing everybody up with his bayonet, and the audience is like, “Yeeaaaahhhh! Confederate soldier! He’s so awesome!” Would you feel weird about that? I would find that strange. And then after the Confederate soldier sequence, Abraham Lincoln himself walks out, but he’s like CGI, and he’s like, “I think we’re gonna win this thing.” And then it goes to credits.

So yeah, Andor completely outclasses the movie it’s supposed to set up, improving on it in almost every way. I can’t pretend otherwise and it’s the fundamental paradox of my love for this series.

At first I assumed the prequelitis was imposed on Gilroy by Lucasfilm or Disney. But in interviews, the showrunner often talks about the shocking creative freedom Disney gave him on the series. “I never took a note,” he claims. So it seems more likely that leading into Rogue One so directly was self-imposed. The logic of handling prequels this way is now standard in Hollywood, so maybe Gilroy never considered doing otherwise, though it’s disappointing in a writer of his brilliance. Maybe he considered it a fun screenwriting problem to solve, to stuff the story into that bottleneck after greatly expanding the scope of Star Wars storytelling over two seasons. At the same time, he detached himself from that process: in this IndieWire interview with Gilroy, we learn that “Star Wars expert” Tom Bissell was brought onto the writing team with the specific task of “help[ing] with the seamless transition to Rogue One.”

Bissell wrote all of the three-episode final arc, and that includes some of the best scenes in the entire series (or all of Star Wars for that matter), the ones that flesh out the relationship between Kleya and Luthen (Stellen Skarsgård) even as it ends in death and tragedy. So I don’t want to be too hard on him, but I take issue with seamlessness as the final goal.

A movie prequel can never be “seamless,” as if the story is a silent comedian stepping from one moving steel beam to another, nor should it try to be. Let’s start with some obvious things: there’s the basic fact of the aging of the stars. Diego Luna is nine years older here than when he shot Rogue One. All the de-aging software at Disney’s disposal can’t take away that cognitive dissonance. Cinematic styles and technology change and evolve too. Movies made now just look and feel different, even or especially if they’re intended to visually match their predecessors.

Beyond those practical considerations, in a larger sense Rogue One is a very different project, made for different reasons and for a different audience. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with two pieces of media telling two different yet related stories with different styles and tones. This is something many fans don’t seem to get at all. Not to be mean but I chalk it up to the cinema illiteracy that’s increasingly rampant in fandoms.

It’s a much larger problem that I won’t get all into here. I have lots of mixed feelings about it; I’ve been a defender of some of the franchises that can be blamed for this dire state of things, including the Marvel Cinematic Universe (I wrote confessionally about my MCU fandom in my review of the terrible Thor: Love and Thunder). Yet cinema illiteracy is a real and growing problem for the film industry and for popular culture more broadly. You can see the way it impacts storytelling — the way writers dumb down Netflix series to appeal to these very literal-minded audience expectations — and it’s distressing to witness.

Anyway, back to the point: What is a prequel in the first place? It’s not just a story that predates the established story. It’s also commentary on that story, an interpretation of that story. And if it was made significantly later than the original installment, as some prequels are, then it’s got the additional task of reworking the themes to comment on the contemporary era. The world is a much different place than it was in 1977; there are many social reasons why Andor is darker and more political than Star Wars.

What are the Star Wars prequels if not late-90s/early-2000s interpretations of the original works — George Lucas taking one of the great villains in cinema history and devoting an entire trilogy to reinterpreting his character for a new generation (for better or worse). I’m insisting on this idea of interpretation because it’s a much more useful way of looking at a prequel or a sequel than seeing it as “canon” that reveals the truth of a story or a character like a sacred text that must never be questioned. Setting aside their middling to poor quality, if you accept that the Star Wars prequels are reinterpretations, it’s totally fine that Anakin Skywalker and Darth Vader don’t really feel like the same person; you don’t need an in-universe explanation.

There’s a whole genre of memes making fun of all the jarring inconsistencies and tone clashes in the Star Wars movies, such as the awkwardness of Luke and Leia’s chaste romance in the original, or the clumsy retconning in the prequel trilogy (Darth Vader actually built C-3PO as a child, why didn’t he recognize him?). This is why I hate the concept of canon. When I watch Star Wars, I’m not looking for evidence of incest. I remind myself that Lucas only made them brother and sister years later. I’m not imagining James Earl Jones’s voice coming from Hayden Christensen’s surgically reconstructed face. I just enjoy the story for what it was intended to be at the time; I read it as a text written in 1977. I know I’m in the minority, but to me this is the only way to watch these movies. The convention of watching Star Wars in “order” must be so weird and disorienting and comical if you see things so literally.

But it’s not just those spectacular examples; it’s also the way fans will pick apart every detail or overexplain every minor discrepancy in the search for that “seamless” experience. They will question why there are women Rebel pilots in Rogue One when there are none in the original trilogy — imagine wanting casting decisions to have been as sexist in the 2010s as they were in the 70s! They will actually say things like, “It makes no sense that there’s house music in Andor when it takes place before Star Wars, and in Star Wars they’ve only advanced as far as big-band jazz” (I’m paraphrasing a real comment I saw on a friend’s post).

This is such a backwards way of looking at it. The fact that Andor comments on and reinterprets Star Wars, and also comments on our world, by referring to the politics and fashions and music of the 2020s, is what makes it so great and compelling. If you expect it to seamlessly match the established entries in tone and feel and music styles, you’re going to be disappointed every time.

And yet, as silly as it sounds when you break it down like that, this is apparently exactly what Gilroy and his team were trying to do in the last episode! The detail that grates on me the most is Mon Mothma’s hair and costume. Poor Genevieve O’Reilly, who is so supremely stylish and regal in Michael Wilkinson’s fabulous costumes throughout the rest of the series, relegated to cosplaying Caroline Blakiston’s frumpy 1983 costume and hairdo in the closing scenes. It’s so dissonant and unintentionally funny.

This is what I call the “Yavin effect,” a corollary to the funnelling effect specific to Andor season 2. Barring the brilliantly satirical early scenes involving the Maya Pei Brigade (which aren’t set at the Rebel base itself), nearly everything that kills the vibe of the season seems to emanate from Yavin.

This is, of course, because Yavin is the Rebel base and a key setting in both Rogue One and Star Wars; so that’s where all the fan-servicey tie-ins to established lore have to take place.

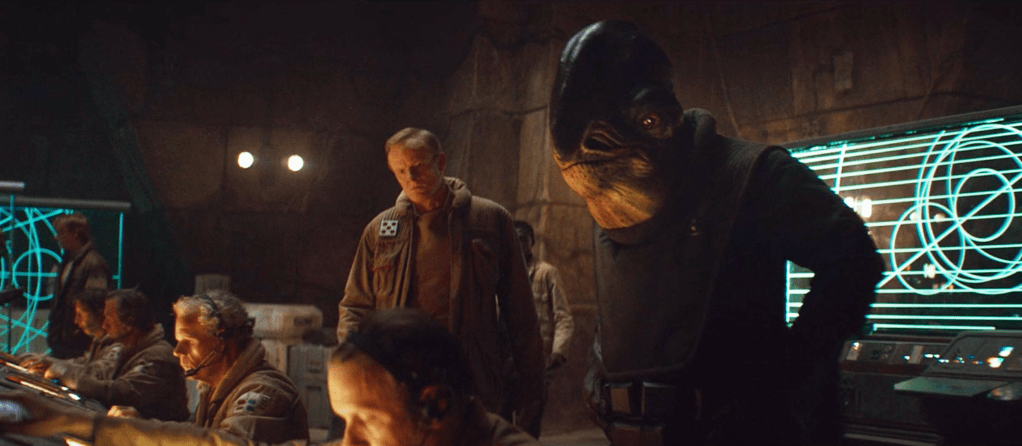

On Yavin, Mon loses her fashion sense, and the Force comes into play again. The story drags, the acting gets worse. Admiral Raddus appears, mumbling and slurring all his words, making an otherwise dramatic exchange seem like Spaceballs or Fraggle Rock (Gilroy was famously reluctant to feature nonhuman species in the series and this scene shows why).

It’s funny in retrospect when Cassian tells Kleya he’s taking her to Yavin, the base of her factional rivals, and she groans, “Yavin. I know all about Yavin.” You said it, sister: my feelings exactly as a viewer.

I’m just grateful the damage is mostly contained to one episode and the brilliance of the rest of the series stands apart.

When I’ve tried to discuss these things with other fans, they often say Gilroy didn’t have a choice: there was no other way to do it because he was constrained by the existence of Rogue One; it had to end this way. Like I said, this is the received wisdom when it comes to prequels now, but I don’t think it’s true at all. I think there would have been any number of ways for Andor to serve as a prequel to Rogue One without being so heavyhanded about it, without leading right into it.

Think of the way The Godfather Part II lays out the origin story of Vito Corleone without leading up to all the events of the first film. The important thing is telling us something about Vito’s past and fleshing out his character, so that we understand him better; the important thing is not getting us to his daughter’s wedding on Long Island.

We already know Vito becomes the Godfather, and in the end is assassinated by his rivals. Everything we need to know about the person he becomes later is illustrated for us in a handful of scenes from when he was young. Not only is it fine that there are years’ worth of untold story remaining in between, in fact it’s much better, because it leaves the rest to our imagination.

The conclusion of Andor could have been handled this way too, if you just let go the idea that we have to see Cassian get on that ship at the end and have everything wrapped up.

If I had to script-doctor the conclusion, I would uncouple the ending from Rogue One as much as possible. I would bring the whole timeline back — say it ends six months or a year before Rogue One instead of a day before. Cassian’s growth as a character could be demonstrated in some other way that didn’t have to do with the Death Star plans, not directly anyway. It could very much still end on a note of heroic tragedy even if his demise wasn’t imminent, as long as it was well-written.

All that would be more in line with the way the rest of the series was written — leaving those blank spaces, leaving us guessing. We don’t need to know what happens to Kino Loy. We know he can’t swim, and the ambiguity of leaving him standing there on the platform looking down as his fellow freed inmates jump in the water is why that scene is so powerful. It’s emotionally wrenching in a way that showing him either drowning or surviving and escaping could never be.

Try this mental exercise: imagine Andor was cancelled by Disney after season 1. Would the story feel incomplete to you? Season 1 is basically Cassian’s Godfather origin story. It tells us the story of where he came from and of his life filled with struggle, paints a portrait of his character, and shows the sequence of events that pushed him to join the Rebellion and start thinking about others besides himself. When he tells Luthen at the end of the season, “Kill me, or take me in,” that’s his entire character development in a nutshell.

Obviously I’d much rather season 2 existed, but if season 1 was all we had due to circumstance, in my opinion it would be enough to make for a powerful prequel. (Note: I wrote all this before reading that IndieWire interview with Gilroy and finding out that ending things after season 1 was indeed a possibility at one point — how fascinating!)

I’m just saying, they could have handled the end of season 2 in this spirit. It’s not hard to imagine at all.

A more radical approach would have been to completely drop the idea of setting up Rogue One, and retcon the whole story. Just let Andor exist in all its glory and go off in its own direction and forget about having to to join up with any other part of the saga at all. Before Furiosa, Mad Max did this regularly: with each new installment Miller would change Max’s backstory or change the nature of the postapocalyptic setting (an energy crash in The Road Warrior, a nuclear war in Thunderdome) without explaining why, so that each sequel was like a subtle reboot in which the timeline meant little if anything. This was something I loved about the saga, the way it avoided “lore poisoning” (a great phrase I saw in an online discussion of this) and all the damn tiresome explanations for everything, and why Furiosa was comparatively disappointing.

Doing this with Andor would have almost certainly sent the fanbase into an insufferable frenzy, but I would have loved it, especially since I don’t really rate Rogue One. Somewhere deep down I think I was secretly, unrealistically hoping for this.

Whether realistic or not, musing on what might have been different about the series points to the larger problem: Andor should stand on its own. To me it’s unfortunate not only that season 2 is chained so directly to Rogue One, but also that its plot is driven by the menace of the Death Star. As I mentioned in my review of season 1, I’m very tired of the Death Star as a plot device in Star Wars. Luke Skywalker blew this thing up in 1977 but the franchise has never been able to get away from it. We’ve had new Death Stars and Death Star-like planet-killing devices and hints about the Death Star in soooo many Star Wars stories. Think about how little dramatic impact there is in The Force Awakens when the Starkiller Base destroys [insert planet name here, I can’t even remember]. I love that movie but that was a silly lowlight. Later they try to own it with self-referentiality, as Han Solo deadpans, “Okay, but how do we blow it up? There’s always a way to do that.” Cleverly letting us know you’re aware of your own tired tropes doesn’t make up for them. This is probably one reason The Empire Strikes Back and The Last Jedi are two of the best entries in the saga: they both completely get away from this trope.

There’s more to dislike about the Death Star trope besides the sheer tedium. As I wrote in my review of season 1, about the revelation that the prisoners on Narkina 5 are manufacturing parts for the Death Star: “Are we supposed to be more appalled at the evil thing they’re unknowingly working on than we are at their exploitation?” After finishing season 2 I would expand on this point: is the Empire bad because it’s fascist, or because it can destroy planets? The whole point of Andor was to get away from the cartoonish space-opera view of evil and show us that horrible things happen in society for structural, not moral reasons. Like the real-life revolutionaries they are modelled on, Luthen’s militants fight the Empire in season 1 because it’s authoritarian and oppressive, not because it’s “evil.” Conversely, Dedra doesn’t serve the Empire because because she’s innately “evil.” She’s not eager to torture and commit genocide, but like real-life fascists and “good Germans,” she convinces herself these things are necessary because it will make for a better future. This is far more unsettling than blowing up planets.

The other problem with the Death Star as the eternal McGuffin is that everything becomes about characters and conflicts that were written 50 years ago. It seems we’re expected to find value in the choices and sacrifices of Cassian, Kleya, Vel and the others because of what they can contribute to the already established lore and to the stories of iconic characters like Leia and Luke, not because of what they do in their own right and for their own reasons. At a certain point that’s just weird. I’ll always love the original, but come on y’all, find a new thing to do!

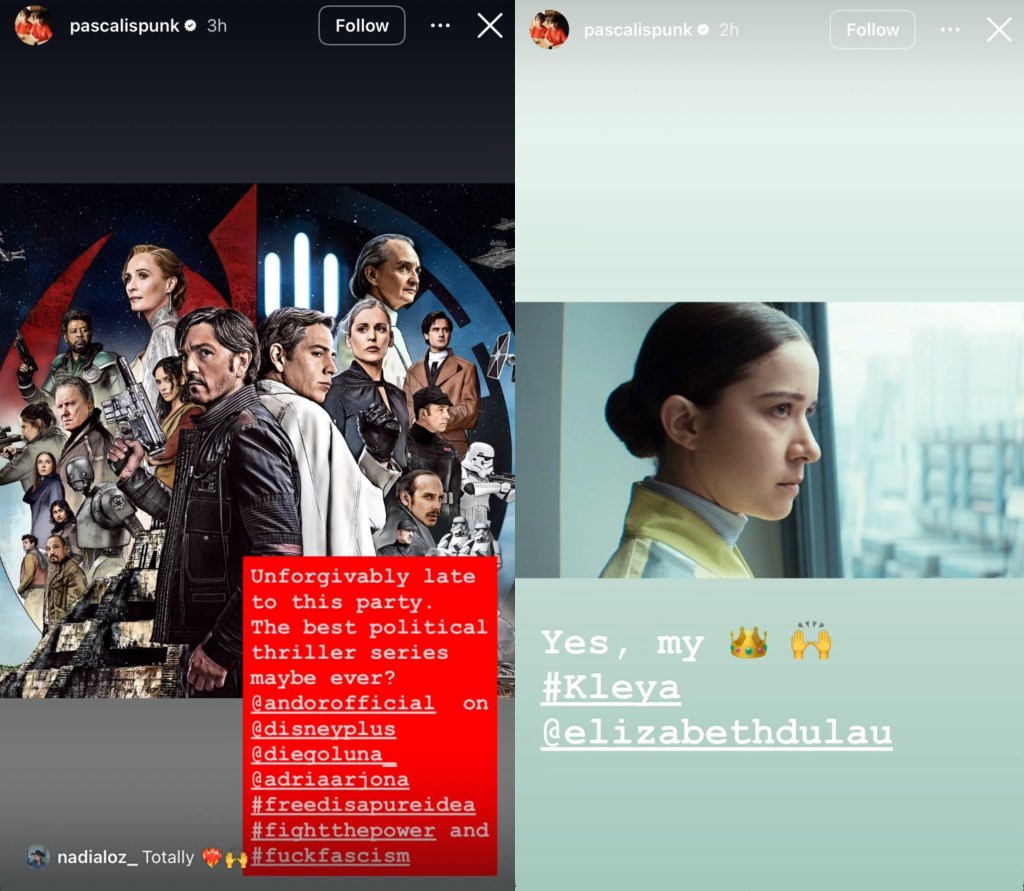

In his Instagram story last year, Pedro Pascal, bless him, called Andor the “greatest political thriller series maybe ever?” (also including the hastag #fuckfascism and correctly identifying Kleya as the heart of the season 2). I love how he didn’t qualify it as the greatest sci-fi thriller or the greatest Star Wars entry, he just bluntly gave it its flowers as one of the best ever, period. I completely agree with him — and it makes me want to ask, why should the greatest political thriller series ever have to answer to a middling Star Wars movie from nine years ago? Or to Star Wars itself?

What about the positives in the finale? In fairness to Gilroy and the cast and crew, they make all this prequelish business about as interesting as it’s possible to make it. The episode works best, which is to say it feels less like Star Wars and more like Andor, when it sets aside talk of the Death Star and takes on a more quiet and reflective tone. There are some very nice dialogue-heavy scenes between Cassian, his former militant commander Vel (Faye Marsay), Mon (despite her unfortunate hairdo), and Kleya. I especially liked the scene in which Vel and Cassian toast the victims of the Empire: “The Ghormans. Ferrix. Your mother. The Dhani.” That felt very real and relatable to our world — this is exactly what we do in real life with the fallen heroes of the left and the martyrs of Gaza. It’s a nice way to tie up the politics of the series.

Andor is at its best when it’s about our world — when it’s about police violence, and creeping fascism, and the oppression of refugees — not about Rogue One, and not self reflexively about Star Wars. It’s at its best when it’s forward-thinking, does its own thing, and raises the bar on Star Wars instead of looking to the past.

Fortunately this is true of most of the series. It sucks that they couldn’t quite stick the landing, but that doesn’t ruin my love of this historically great series. Its greatness is precisely why it has the capacity to disappoint.

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!

Feature image: Diego Luna in Andor season 2 (2025). Image credit: Lucasfilm