UPDATE: my essay about season 2 is up and you can read it here!

For a while at the end of last year, I found myself with no desire to watch movies or series at all. I mentioned this earlier in my essay about Elia Suleiman: with the genocide in Gaza unfolding in real time, the whole concept of entertainment seemed strange to me. Though I certainly needed a mental and emotional break after seeing so much death and destruction livestreamed all day, I discovered I couldn’t turn off my mind enough to watch a movie for fun. It just didn’t feel right. Nor could I read much either. As often as not I just defaulted to looking at my phone a bit (again!) before crashing out early.

This was depressing to say the least, and didn’t contribute to feeling more focused or politically productive, but instead adrift and alienated and tired.

The week of Halloween (so, just a few weeks into the genocide), I tried watching a couple of horror B-movies just to blow off steam. It didn’t really work: as mediocre as these flicks were, the onscreen horror just reminded me of real-life horror (leading me to theorize about the role the horror genre plays under capitalism, but that will have to wait for another essay!). So I reverted to not watching much of anything at night.

For all the same reasons, I also felt unable to write about culture and have it mean something in the face of such a crisis, and so this blog took a hiatus for months.

After a few weeks, I found I wanted to watch films again, but I wanted them to be about Palestine. So I went on a journey through Suleiman’s Palestine trilogy, and that was a great and constructive way to get back to being myself and actually relax at night, while contemplating the history that led to the current bloodshed. That unlocked my ability to write about culture again; the result was my essay about Suleiman. Writing about Palestinian cinema felt like the right thing to do in that moment.

After a few weeks, it became apparent that protesting and organizing against the genocide was going to be a marathon and not a sprint, and I was able to convince myself to release some tension and settle back into some normal routines. Of course, nothing felt the same anymore — these events have changed us and are still changing us in ways it will take years to process I believe — but I was now at least able to find moments of relaxation and enjoyment.

But I was still at a loss for what to watch. I found my enjoyment of movies or shows that didn’t have something to say about the world we live in was greatly diminished. At the same time, it’s not like I craved political documentaries, like many of my comrades do (god bless them). I didn’t want that much reality; I still wanted to be able to sink into a fictional world — I just wanted it to have resonance with our world too, if that makes any sense.

Around this time I found myself thinking about Andor a lot (note: I’m not going to call it “Andor season 1” here; season 2 is still a year away and at this point I’m still thinking of the first season as a standalone work). I loved it when it first aired — and I wrote a long essay about it, which you might want to read first so you have some background on my view of the revolutionary politics of the series, and of Star Wars more broadly.

I’d been wanting to rewatch Andor for a while, and I started to realize that the reason I couldn’t stop thinking about it — the reason certain scenes and certain lines of dialogue were flickering in the back of my mind like a dream I couldn’t shake — was because its story contains so much that could apply to Palestine and Palestinian resistance.

I decided it was the right moment to revisit Andor, this time with the specific aim of having it be a meditation on Palestine. I would only look for things that work as references and allusions to Palestine, direct or otherwise.

My instincts were correct: not only was it absolutely worthwhile diving back into it — honestly I was overpowered by its brilliance once again, if not more than the first time — but watching it with Palestine in mind, using Palestine as a key to unlock its meaning as it were, was really valuable and inspiring.

The story elements of Andor that relate to Palestine can be roughly divided into three categories: overt allegories; more general references to colonialism or oppression that are also very much “about” Palestine without much of a stretch; and the way the story arc can be retroactively read as an eerily prescient analogy to Palestinian armed resistance on October 7. I’ll take a look at each of these three tendencies in order.

There is, I believe, one clearly intended reference to Palestine in Andor — one bit that refers only to Palestine and nothing else. In episode 5 (“The Axe Forgets”), there’s a poignant exchange between Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) and fellow Rebel insurgent Arvel Skeen (Ebon Moss-Bachrach — you know, the one from The Bear). Skeen tells of how an Imperial prefect forcibly took his brother’s pepper-tree farm, and then flooded it; his brother committed suicide as a result. That can’t be anything but an explicit reference to land theft and the destruction of olive trees in Palestine. For decades, Israeli settlers and the IDF have cut down and burned olive trees in the West Bank and Gaza. The reason for this wanton destruction is because the often centuries-old trees symbolize Palestinians’ deep connection to the land.

It turns out the traitorous Skeen is lying about this, but it’s clear his fake backstory is intended to refer to reality under the Empire, because it sounds plausible to his listeners. Neither Andor nor the other members of the small Rebel band on Aldhani question the story at all.

Another important scene is centered around an all-but-direct reference to the Palestinian struggle. In the climactic episode, “Rix Road,” Imperial stormtroopers on Ferrix attack the funeral procession for beloved dissident Maarva Andor (Fiona Shaw), Cassian’s adoptive mother. It turns into a deadly riot and mass uprising that represents the dawn of the Rebellion.

In real life, Israeli cops and soldiers are notoriously prone to attacking Palestinian funerals. A noteworthy recent instance took place at the funeral of Shireen Abu Akleh, the Al Jazeera journalist and Palestinian national hero who was assassinated by the IDF in 2022. Israeli cops swung batons at the crowd of mourners, detonated a stun grenade, smashed the windows of the hearse, and knocked her coffin to the ground.

There’s one more bit of backstory that may not be intended as a reference, but in our reality can only refer to Palestinians: the fact that Cassian Andor was imprisoned by the Empire as a teenager. This is significant as one of the experiences that leads to his radicalization.

Israel is currently the only nation on earth that systematically prosecutes children in military courts. Between 500 and 700 Palestinian children are tried in Israeli military courts every year; 10,000 Palestinian children have spent time in the Israeli military detention system since 2000. Torture is rampant in these facilities, and that includes the torture of incarcerated children.

Now let’s look at the more broad category of indirect references. As I discussed in my earlier essay, showrunner Tony Gilroy brought many historic influences into Andor — the Russian Revolution, Irish nationalism, the Vietnamese people’s struggle against the United States (especially noteworthy as that was the core analogy in George Lucas’s original vision), and various Indigenous liberation struggles, among others. Palestine is but one of many real-world influences on the show’s wonderfully textured and lifelike fictional rebellion. Gilroy is explicit about this in interviews:

There are things all the way through the show, and I don’t want to go through and quote chapter and verse, but this is the Russian Revolution. This is the Montagnard. This is something interesting that happened in the Haitian Revolution. This is the ANC. This is… Palestine. This is the Continental Congress. This goes all the way… I mean, you could drop a needle in the last, I don’t know what is recorded history, 3,000 years — slavery, oppression, colonialism, bad behavior, betrayal, heroism, it’s a continuum.

With all these strands woven into the story, it’s apparent that Gilroy is a voracious reader who’s interested in many periods of history. It’s also clear he has at least some sympathy for the left — and by the way I love that he mentions the African National Congress and Palestine in the same breath as the Russian and Haitian revolutions.

But because Palestine is such a fundamental issue for anyone concerned with liberation anywhere — because oppressed people all over the world from South Africans to Indigenous Australians have looked to and been inspired by the Palestinian struggle for decades — even the parts of Andor that don’t directly invoke Palestine can be taken as commentary on it without having to move much around.

To start with one very relevant example: the scene in episode 7 (“Announcement”) in which Andor is unjustly detained by shoretroopers and is lucky to survive being choked by a police droid is overt commentary on police violence in the US in the wake of the George Floyd rebellion in 2020. One of the talking points during that summer of resistance was the exchange programs between US police forces and their counterparts in Israel. Amnesty International and Jewish Voice for Peace are among the organizations who have campaigned for years against what JVP terms the “Deadly Exchange” — American and Israeli cops sharing their “worst practices” of racial profiling, brutality, and militarized repression of dissent. American police also receive training in Israel. So that scene could double as commentary on Palestine.

The series contains many references to colonial land theft and genocide on different planets around the galaxy. Andor himself is an Indigenous Kenari; his home planet was colonized by miners during the Republic era — a reminder that colonialism is not just a malignant feature of fascist governments like the Empire, but also an integral part of bourgeois democracy under capitalism (yes, the Republic was capitalist, as the Star Wars prequels make clear).

One thing that’s so valuable about Andor is the way it opens up conversations about these things among nerds. Check out this article on a fan site called the Dork Side of the Force. It makes that exact same point about the Republic’s colonialism: “Countries that we have been taught to understand as ‘the good guys’ exploited the resources and people of rest of the world.”

I’ve seen this kind of thing a lot in various fan forums discussing Andor — you can hardly avoid it considering how explicitly political the show is — and it always makes me smile. It’s a small but heartwarming indicator of the sharp increase in political education and consciousness that’s taken place in the past several years (and which has been greatly accelerated by the Palestine solidarity movement).

The most chilling moment in the series comes in episode 9 (“Nobody’s Listening!”), when we hear about one of the Empire’s genocides during the scene in which Bix Caleen (Adria Arjona) is tortured by Imperial security. The ghastly Doctor Gorst (Joshua James), modelled on Nazi scientists, has developed an innovative form of psychological torture using the recorded screams of the Indigenous inhabitants of a moon called Dizon Fray; apparently the screams have a quality that causes extreme distress and psychological damage in the listener. Gorst tells Bix that the screams of the Dizonite children are especially traumatizing to hear.

Thankfully the viewer doesn’t actually have to hear them; but the suggestion is much worse than anything the sound designers could have come up with.

This scene really creeped me out the first time; I found myself thinking about it a lot even months later, and I felt a sense of dread going into it again. This time, hearing about the cries of those children was tough with the genocide of children happening in real life.

We learn the Dizonites were completely exterminated so the Empire could build a refuelling station on the moon. This is not just some abstract evil shit dreamed up by Gilroy. When you consider that the history of colonialism includes Native people being wiped out for the sake of beaver pelts in North America; or when you read about the horrors done to the people of the Congo, including children, by Belgian colonizers in the name of the rubber market, it’s very plausible indeed.

This all leads in a straight line to the occupation of Palestine, the most virulent instance of settler-colonialism remaining in the world today. The history of colonialism and genocide is not over, and thousands of children are still being killed over real estate even as I type this.

We also find out about the Empire’s campaign of Indigenous displacement on the planet Aldhani — a name obviously intended to echo Arabic place names, making it more poignant in context of Palestine. Over the previous ten years, the Dhani people had been driven out of their highland homes and corralled into “enterprise zones” in the lowlands so the Empire could build a garrison and airfield.

The Dhani, who practice a kind of Indigenous religion that becomes a plot point in the series, are considered simple and superstitious people by the Imperial troops. The Imperials’ racist contempt for the Dhani is plain (there are remarks on their body odor, for example). Watching the heavily armed troops resentfully escort the Dhani faithful to the site of their ritual, it’s not hard to imagine all the oppression and violence that has accompanied the displacement. It’s not hard to imagine how many times a Dhani boy would have been pulled up by stormtroopers for looking the wrong way or for running the wrong direction before being shot and killed.

As I argued before, these dynamics have always been part of Star Wars — there have always been tense encounters with occupying stormtroopers — but Andor makes them more overt and queasily realistic.

In addition to Palestine, these scenes invoke the history of Native displacement in North America, including the bloody campaigns against the Cherokee and the Lakota. Those “enterprise zones” sound very much like reservations to me.

Unlike the case with Dizon Fray, it’s never outright stated that genocide has taken place on Aldhani, but we don’t have to wonder. Displacing tens of thousands of Indigenous people from their homes is an act of genocide in and of itself, requiring extreme violence. There’s no such thing as a peaceful forced migration, and it’s never in the best interests of the victims, whatever justifications are given — whether it’s the Trail of Tears or the Nakba.

Aldhani is the setting for the turning point in the series, and perhaps in the fictional history of the Rebellion too: the raid on the Imperial garrison by a small band of Rebel militants, with freelance criminal Cassian Andor playing a key role. This plays out in the tense and lights-out-brilliant sixth episode, “The Eye.”

The objective of the militants is the theft of the quarterly Imperial payroll for the sector. The payroll — which is hard currency in the form of some kind of bouillon, a charming example of the almost steampunk anachronism in the Star Wars galaxy — will certainly advance the rebel cause materially, but the real point is to strike a blow against the arrogance of the Empire and to gain a propaganda victory.

In that it’s a smashing success. The “terrorist” raid catches the Imperials completely off guard. News of Aldhani causes shock and panic throughout the Empire for its brazenness and its exposure of weaknesses in the military and security agencies, previously thought to be impervious. “Surprise from above is never as shocking as one from below,” says Karis Nemik (Alex Lawther), the revolutionary-theorist-turned-militant who writes the manifesto that changes Cassian Andor’s life, but who is tragically killed in the raid.

Amid the political turmoil and gnashing of teeth following Aldhani, the Empire cracks down hard, imposing a series of draconian emergency measures that threaten the already teetering democracy of the galaxy: increased taxes, an expansion of the criminal code, longer prison sentences. In this there are echoes of the aftermath of 9/11 and the Homeland Security Act, as well as Nazi Germany.

One fascinating aspect of these scenes is that they include the galactic media as part of the story — much more so than any other Star Wars franchise entry I’m familiar with. Syril Karn (Kyle Soller) and his mother Eedy (Kathryn Henry) hear breaking news about “distressing reports” of a “terror attack.” “Rabble,” Eedy says. “They’ll regret it.”

This is very interesting because it’s the first time in Star Wars, as far as I remember, that we have insight into the thinking of ordinary civilians who believe the Empire is good. And of course they get their news from media that is firmly entrenched in Imperial ideology.

Because this is a satire of the news in our own world, it’s not hard to imagine all the ways this galactic media would spin the rebels as bloodthirsty terrorists — remorseless killers and hostage-takers — while suppressing discussion of the economic and social reasons the Rebellion exists at all. It’s not hard to imagine that the media would serve the interests of the Empire and the galactic ruling class — the ancestors of the wealthy war profiteers we glimpse on Canto Bight in The Last Jedi. This would be true even if the media was privately owned and independent. There are several fascinating indicators of the capitalist nature of the Empire in Andor, reminding us that fascism is merely a stage of capitalism in crisis.

But, importantly, the Aldhani raid is also a beacon of hope for the oppressed and downtrodden throughout the galaxy. Aldhani is the moment when the nascent Rebellion escalates from underground organizing and living in fear to open resistance. We get the sense that for the majority of people in the galaxy, that’s good news, not a source of terror as the Imperial-slanted news would have them believe.

This is most poignantly expressed in the reaction of Maarva Andor (who doesn’t know that her son was involved in the raid):

Yesterday, I heard about this attack at Aldhani… I heard that, I put on my best coat, and I walked across the square with a smile on my face. If there are heroes brave enough to take on a whole Imperial garrison, I’m brave enough to stick it out here.

Because of Aldhani, the terminally ill Maarva resolves to stay and join the Rebellion, organizing against the Empire on Ferrix with the short time she has left, rather than fleeing with Cassian.

I love the implications of this dialogue between Andor and Luthen Rael (Stellan Skarsgård) in episode 3 (“Reckoning”):

Andor: They’re so proud of themselves, they don’t even care. They’re so fat and satisfied, they can’t imagine it.

Rael: Can’t imagine what?

Andor: That someone like me would ever get inside their house, walk their floors, spit in their food, take their gear.

Rael: The arrogance is remarkable, isn’t it? They don’t even think about us… These days will end, Cassian Andor. The way they laugh. The way they push through a crowd. The sound of that voice telling you to stop, to go, to move. Telling you to die. Rings in the ear, doesn’t it? … Soon enough, they’ll have something else to listen to.

Then there’s the reaction of Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly), the wealthy Imperial senator and covert Rebel who’s been funnelling money to the militant cause. She’s shocked when she find outs Rael was behind Aldhani. “You realize what you’ve done?” His reply: “You knew where this was going. You’ve always known.”

Mothma will come around: she eventually becomes the leader of the Rebellion. But this is an apt illustration of the political tension between supporters of armed resistance, and liberals who may support the oppressed in theory but who cling to their belief in peaceful means of liberation — through reform or the granting of freedom and civil rights by governments.

You already know where I’m going with all this: it struck me so much this time how similar Aldhani is to October 7 and the breakout of Gaza. Think about it: the cunning use of the most bare-bones weapons and gear by an outnumbered force of desperate militants to strike a devastating blow against a powerful military. The shocking audacity of it — for the enemy it seems to come from nowhere, and represents a total failure of their vaunted intelligence operations. The way it took months and even years of careful planning under their noses. The way it was secretly funded by sympathetic elites.

And then the aftermath: the widespread panic about terrorism, the blame game, the vengeful redoubling of police and military oppression in reaction. The kindling of more rebellion. The overnight change in the political situation and the balance of forces. The message it sends not only to the enemy but to the oppressed of the galaxy too: whatever happens next, things are no longer going to be the way they were. The pivot in the struggle from which there is no going back.

There’s only so far the analogy goes: the fictional raid and the real-life one represent very different operations with different goals. Aldhani is a robbery, first of all; and also an offensive attack by militants who’ve travelled from around the galaxy to embed themselves close to their target and break in as spies. It’s not a breakout — it’s not a defensive response by an Indigenous people to occupation and genocidal containment, as Al Aqsa Flood was (if it were more like the latter, the Dhani themselves would have conducted the raid, right?).

Beyond that, the Empire has much more in common with the United States in its domineering control of the galaxy (explicitly intended by Lucas, remember) than it does with the small settler colony of Israel.

Aldhani is also nowhere near as bloody as Al Aqsa Flood, and this may be the one thing that might make some question the comparison. Instead of hundreds being killed it’s dozens at most, and none of them are civilian noncombatants.

Or are they? The Rebels do take civilian hostages — the wife and son of an Imperial officer (Michelle Duncan and Alfie Todd) — and say they are willing to kill them. Whether they actually do or not is not addressed, and is left to the viewer’s imagination — a brilliant bit of ambiguity in the screenplay.

This is made more complex and dramatically compelling by the fact that in an earlier scene, we spend some time with the family and get to know them a bit. It’s not that we sympathize any more with the horrible things the Empire does because of this — perhaps it would be akin to humanizing the wife and child of a Nazi officer for dramatic purposes. It’s just another little storytelling wrinkle that makes it more visceral when the Rebels are putting guns in their faces.

It doesn’t even matter if the Rebels kill civilians or not in this case. The point of these scenes is to demonstrate that the Rebels, including Andor, are capable of doing some pretty ugly things for what they see as a just cause.

This has already been established in Andor’s character: the very first thing we see him do in Rogue One is ruthlessly kill an informant who’d done nothing wrong, as far as we can see, simply to protect the information he’d been given. That scene introduced some dark realism about war and espionage into Star Wars, deepening tendencies that had always been there (“Han shot first”), but had always been rendered cartoonish and loveable by the space-opera milieu.

In Andor, even more than in Rogue One, the space opera has been done away with so we can better see our Rebel heroes as the complicated freedom fighters they really are. It leaves us with no doubt that there must have been a lot of this kind of thing during the nine years of the Galactic Civil War. As Rael says, “I burn my decency for someone else’s future.”

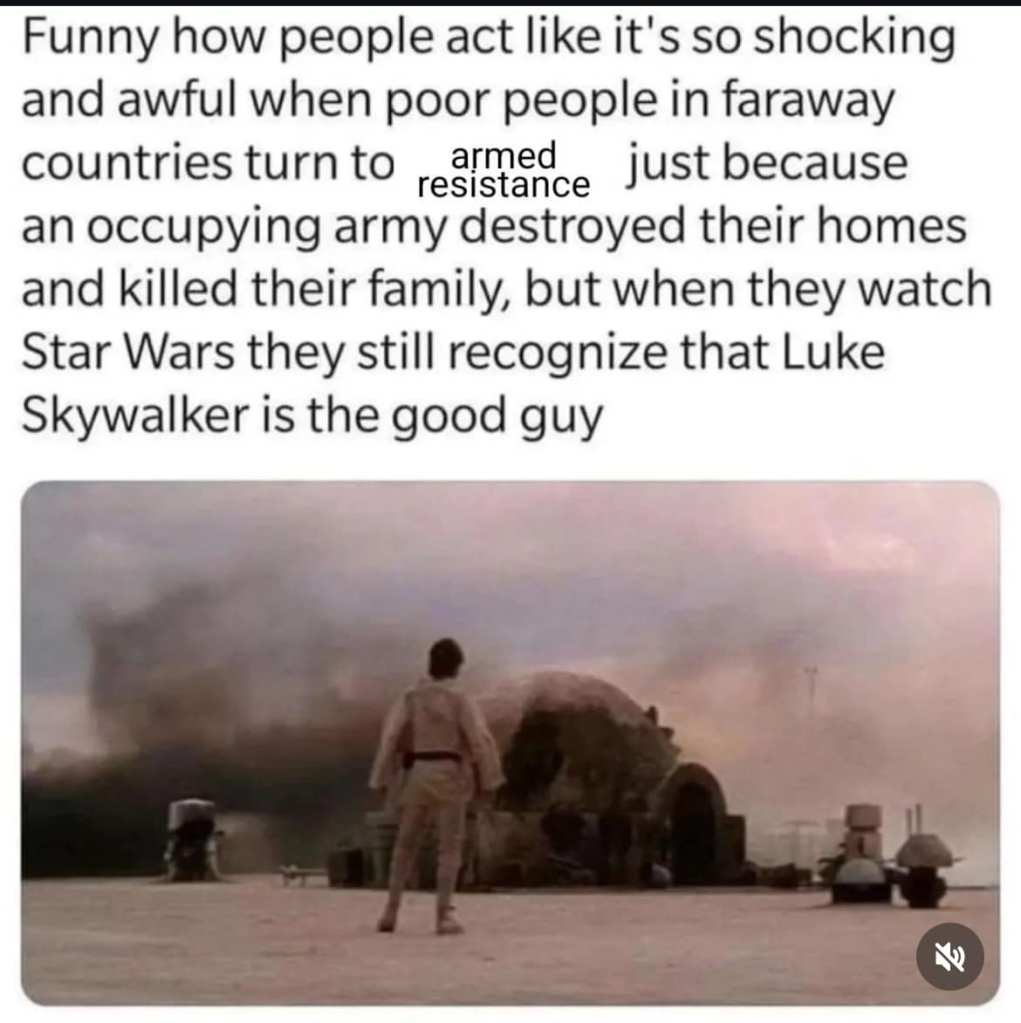

This is not a moral judgment one way or the other; it’s just being objective. This is the bloody nature of struggles for liberation. This is what it takes to fight against a much stronger, much better-equipped oppressor — who is, it must be said, the real cause of the violence in the first place. It’s wrong to equate the violence of the oppressor with the violence of the oppressed.

If this is hard for you to swallow, don’t read up on the French Resistance, or the Haitian Revolution, or the various Native campaigns against the colonists in North America, or John Brown’s antislavery crusade. Don’t look into the Viet Cong’s war against their American invaders — George Lucas’s favorite anti-imperialist freedom struggle.

And if you have difficulty with the idea of “terrorism” — just remember something Nelson Mandela said:

I was called a terrorist yesterday, but when I came out of jail, many people embraced me, including my enemies, and that is what I normally tell other people who say those who are struggling for liberation in their country are terrorists.

Reasonable people support slave revolts and Indigenous resistance. We don’t celebrate the killing of civilians, but we support the fundamental human right of the oppressed to revolt. This is not a contradictory position. You either support the oppressed or you don’t.

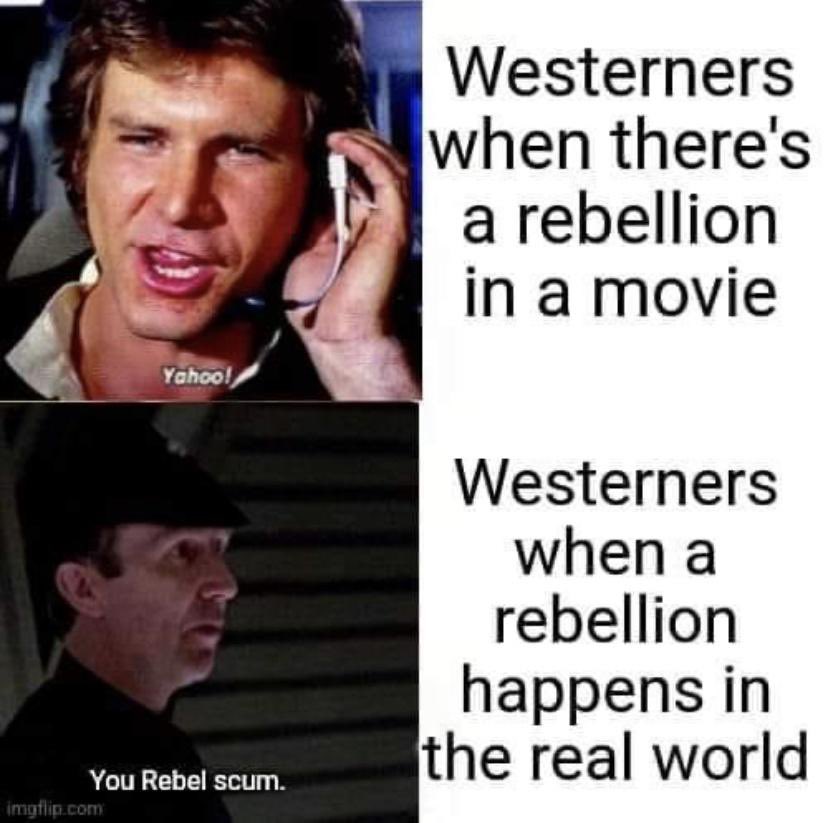

This is a talking point that’s become so widespread it’s turned into a meme as the pro-Palestine movement keeps growing: a lot of people naturally root for resistance fighters in movies, but have a hard time with it in real life.

There were so many other things I loved about Andor on my second pass through it. I can’t get to them all or this would turn into another epic, and it’s already long enough, especially for a second piece of writing about the series.

I really enjoyed the world-building. I don’t particularly care about “canon,” or at least not in the way most fans do, obsessing over it to the exclusion of cinema and storytelling. I don’t care about how the story of Andor ties in to the Clone Wars or what it prophesies about the events of the original trilogy. It’s a compelling enough work of drama to stand on its own. You wouldn’t need to be a fan of Star Wars at all in order to appreciate it, and this is pretty much the first time that’s been true since 1977.

What I do like is the way Gilroy and his collaborators (especially the excellent design team) mine the franchise’s history in order to enrich the drama. In this context, the Easter eggs and little bits of fan service (speeder bikes, Kyber crystals, blue milk, revisiting the Imperial Senate chamber) work as brush strokes on a canvas, as fascinating bits of texture that help create a believably lived-in world. They aren’t the entire point, as they are in the more indulgent episodes of The Mandalorian, for example.

This is all to say I spotted a few more of those Easter eggs this time, and that was fun, but it never got in the way of the story.

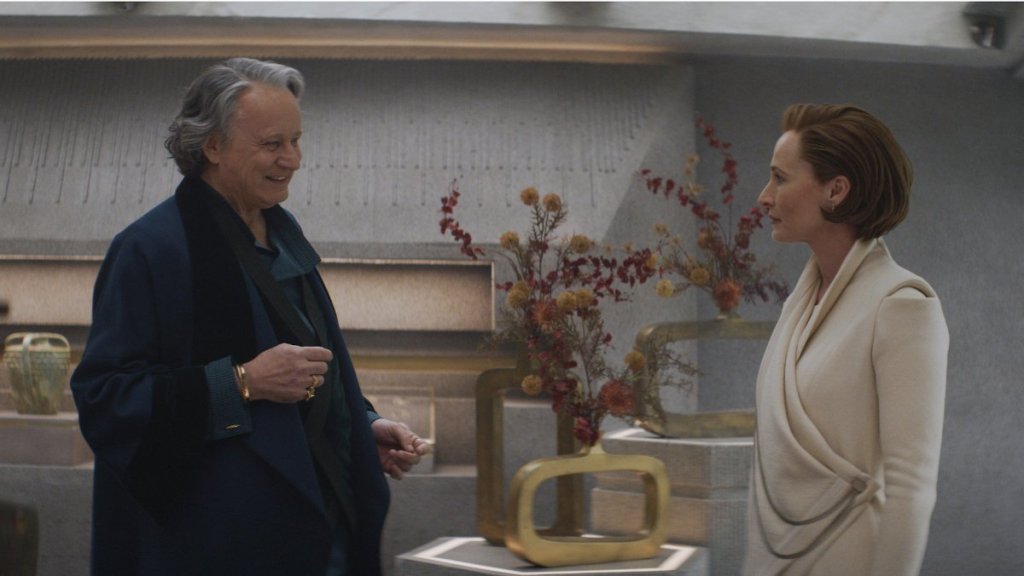

I found that several of the things I criticized about the series in my last essay were smoothed over for me — especially Mon Mothma’s storyline. Previously I didn’t like spending so much time with the intrigues of the galactic bourgeoisie and Mothma’s covert, high-stakes financial support for the Rebellion, and I found all the hushed conversations at cocktail parties a bit tedious. But with adjusted expectations I found these scenes much more fascinating and gripping; especially thanks to O’Reilly’s superb performance.

One thing I really appreciate about the depiction of the Rebels’ bourgeois benefactor and future leader is that it shows how messy and complicated revolutions are. To borrow a concept from Lenin, revolutions don’t happen with the oppressed lining up on one side and the imperialists on the other as if it were a football game. The play out in all kinds of arenas and at many levels of society, among the middle classes as well as workers and the oppressed and the “non-conscious” masses, with good and bad politics, and good and bad strategies. Just think of the way the Iranian revolution of 1979 was characterized by a volatile coalition of workers, communists, peasants, small-business owners, and religious fundamentalists, who all had their grievances with the U.S.-backed capitalist class that ran the country — before it deteriorated into a counterrevolution and the fundamentalists won out.

“Whoever expects a ‘pure’ social revolution will never live to see it,” Lenin wrote. The strength of Andor is the trouble it takes to show us these many contradictory elements of revolt against empire.

Some fans maintain that Andor is the best Star Wars ever. As much as I love it, I resisted this idea at first. My attachment to the first one is just too fundamental to my personality (I was six when it came out, the perfect age for it to shape my outlook on everything). But as I sank deeper into Andor this time I started to think maybe it really is the best. It takes all the most interesting things about this 47-year-old franchise and hammers them into something so powerful and relevant.

There’s a thing that happens to me, a very rare thing I’ve experienced with just a handful great sci-fi films, including The Matrix, Children of Men, and Dune Part Two: they make such powerful, revelatory points about our own world that I feel like what I’m watching isn’t quite fiction. It’s a really specific feeling I got from Children of Men when it was new, a feeling in the pit of my stomach almost like an anxiety attack. Despite how fanciful the dystopian scenario is with its worldwide collapse in fertility and its miracle birth, it felt like some kind of cinéma-vérité or hybrid documentary. Every dystopian thriller is about our world, but it takes intelligent writing and an actual political perspective to make it really resonate truthfully like that.

Andor does that exact thing, and that was the first time Star Wars had ever had that effect on me. And the reason it did that is because its politics are so spot-on that it feels like it’s got something to say to us. That feeling was very strong the first time I watched it, as I wrote before — that sense that “One way out!” and “Fight the Empire!” were about us. That feeling was even stronger watching in light of Gaza. Even in the face of all this real-life horror, it made me think about real-life resistance — real-life rebellion — and that was profoundly inspiring.

Like what you read and want to support? Consider buying me a coffee! You can also subscribe below, and be sure to share this article!

Feature image: Stellen Skarsgård and Diego Luna in Andor (2022). Image credit: Lucasfilm

Thank you for your very interesting article. The similarities between the Genocide in Gorman and the horrible ongoing Genocide in Gaza is mind-blowing. The resistance forces are called terrorists and media whitewashes their lies and those occupying forces killed in action are named as heroes.

The end of this tyrant empire in the real world is near!

Free Palestine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading Arash! So awesome that it’s not just me who sees those real-life parallels when I watch. By the way, in case you missed it, I get more into this in my article about season 2, which I just published recently: https://underthepavingstones.com/2025/09/06/andor-season-2-is-revolutionary-tv/

LikeLike